Edmontosaurus

Name:

Edmontosaurus

(Edmonton lizard).

Phonetic: Ed-mon-toe-sore-us.

Named By: Lawrence Lambe - 1917.

Synonyms: Anatosaurus, Anatotitan,

Claosaurus annectens, Edmontosaurus saskatchewanensis, Hadrosaurus

longiceps, Thespesius saskatchewanensis, Trachodon longiceps.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria,

Ornithischia, Ornithopoda, Iguanodontia, Hadrosauroidea, Hadrosauridae,

Saurolophinae.

Species: E. regalis (type), E.

annectens.

Diet: Herbivore.

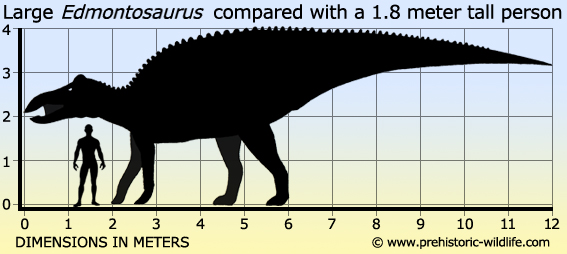

Size: Adults from 9 to as much as 12 meters

long. Largest individuals potentially up to 13 meters long. The

species E. annectens used to be widely considered

as being smaller

than E. regalis, but fossil analysis starting

from the early

twenty-first century has now hinted that E. annectens

was probably of

a similar size to E. regalis.

Known locations: Canada, Alberta and

Saskatchewan, and the USA, including the state of Montana, South

Dakota and Wyoming.

Time period: Late Campanian to Maastrichtian of the

Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: Multiple individuals,

including almost complete skulls and postcranial skeletons, but

mummified soft tissues as well as soft tissue impressions on rocks

surrounding skeletons. Bone beds including the remains of many

thousands of individual Edmontosaurus are known.

Edmontosaurus is without a doubt one of if not the most intensively studied hadrosaurid dinosaur. Not only are there many Edmontosaurus specimens known, but those that have been recovered include some of the best preserved hadrosaurid material so far found.

Classification history

Edmontosaurus

has one of the longest and most complicated taxonomic histories of any

dinosaur, and it is a subject that would need an entire article in

its own right to explain properly. The first Edmontosaurus

fossils

were being found at least as far back as the late nineteenth century

during a period in American paleontological history known as the

Bone Wars. During this period two rival palaeontologists, Edward

Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, were desperately trying to

outdo one another by naming as many new prehistoric animals

(including but only dinosaurs) that they could. This led to a

great many genera and species being created quickly without adequate

study, and the task of identifying them properly fell to later

palaeontologists.

The

first Edmontosaurus fossils to be named were by

Edward Drinker Cope in

1871, but Cope named the remains as belonging to a species of

Trachodon (today regarded as a dubious genus of

hadrosaur), T.

atavus. Later in 1892, Cope’s rival Othniel Charles

Marsh named

another new species, Claosaurus annectens.

During this period most

hadrosaur fossils were being named as other earlier established generas

such as Trachodon, Diclonius,

Claosaurus and Hadrosaurus.

Not all

palaeontologists were in agreement as to what was and was not valid

however, and published opinions varied greatly between them.

The

first establishment of the name Edmontosaurus came

in 1917 when

Canadian palaeontologist Lawrence Lambe who at the time was naming two

partially preserved individuals recovered from the Edmonton Formation

(today known as the Horseshoe Canyon Formation). Lambe established

the type species as Edmontosaurus regalis, and

noted how the two

specimens appeared to be similar to another species named Diclonius

mirabilis.

In

the 1920s further hadrosaur species such as Thespesius

saskatchewanensis and Thespesius edmontoni

were named. However,

by the 1930s palaeontologists were starting to take note that many

of the older species assigned to early genera did not quite fit in well

where they were. Ultimately in 1942, Richard Lull and Nelda

Wright created an entirely new genus called Anatosaurus

which was based

upon Claosaurus annectens, and also included

other species such as

Thespesius edmontoni, T.

saskatchewanensis and Trachodon

longiceps. This led to the Anatosaurus

genus being represented by the

species A. annectens (type), A.

copei, A. edmontoni,

A. longiceps, and A.

saskatchewanensis.

Although

essentially a wastebasket taxon for holding various species that just

didn’t fit, Anatosaurus quickly became well known

in popular science

concerning dinosaurs. The name Anatosaurus

literally translates as

‘duck lizard’ in reference to the duck-like bill that Anatosaurus

would have had in life, and due to its popularity, the hadrosaurs

subsequently became more commonly known as the ‘duck billed’

dinosaurs. During this time, almost every depiction of a

duck-billed dinosaur was of an individual of Anatosaurus.

Towards

the end of the twentieth century our understanding of hadrosaurs and

particularly both Anatosaurus and Edmontosaurus

was again changing.

The trigger event of this was the studies of Michael K. Brett-Surman

who was examining the Anatosaurus fossils as part

of his graduate

studies. Brett-Surman came to the conclusion that all of the

Anatosaurus species with the exception of A.

copei and A.

longiceps, actually belonged to the older Edmontosaurus

genus,

though as a distinct species to the type species E. regalis.

Although Brett-Surman’s papers were not capable of being officially

recognised by the ICZN, they did get the attention of other

palaeontologists who agreed with his reasoning. The type species of

Anatosaurus, A. annectens

(originally Claosaurus annectens),

was used to create Edmontosaurus annectens, with

all others except

A. copei and A. longiceps

additionally being assigned to the

species.

Towards

the end of the twentieth century our understanding of hadrosaurs and

particularly both Anatosaurus and Edmontosaurus

was again changing.

The trigger event of this was the studies of Michael K. Brett-Surman

who was examining the Anatosaurus fossils as part

of his graduate

studies. Brett-Surman came to the conclusion that all of the

Anatosaurus species with the exception of A.

copei and A.

longiceps, actually belonged to the older Edmontosaurus

genus,

though as a distinct species to the type species E. regalis.

Although Brett-Surman’s papers were not capable of being officially

recognised by the ICZN, they did get the attention of other

palaeontologists who agreed with his reasoning. The type species of

Anatosaurus, A. annectens

(originally Claosaurus annectens),

was used to create Edmontosaurus annectens, with

all others except

A. copei and A. longiceps

additionally being assigned to the

species.

At

the time of writing there are two established species of

Edmontosaurus, the type species E.

regalis and

the later named

E.annectens. Analysis of known fossils and their

locations shows that

both of these species lived in the same locations as one another but at

different times, with E. regalis being

recognised as a Campanian

only era species, and E. annectens being a

later Maastrichtian era

species. This indicates that E.annectens replaced

E. regalis as the

dominant Edmontosaurus species.

Edmontosaurus as a living dinosaur

Hadrosaurid

dinosaurs can be divided into two main groups, lambeosaurines (with

Lambeosurus

as the type genus) which had hollow bony crests on their

skulls, and saurolophines (with Saurolophus

as the type genus)

that had solid to no bony crests on their skulls. Edmontosaurus

belongs to the latter group as the bone skull itself has no ornamental

protuberances, though soft tissue display structures could have still

been present, as indeed now seems the case.

As

previously mentioned above, Edmontosaurus is

represented by some of

the most numerous and best preserved fossil remains known, which

probably makes Edmontosaurus one of the best

understood hadrosaurs.

With that said however we must not let ourselves get over confident as

it was only in 2013, almost a century after the genus was first

named, that Edmontosaurus was discovered to have

had a small soft

tissue crest on the top of the skull. This crest was fairly small,

situated on top of the skull above the eyes to the back of the

skull, and has only been preserved as an impression on the rock

surrounding the bones. It’s possible though that this feature might

had been found sooner considering that in the very early days of

palaeontology, collectors would only concentrate upon extracting

fossil bones without looking for surrounding features. Indeed, many

potential soft tissue impressions of such areas as skin and muscle

tissue have been known to have been destroyed by collectors who only

cared about bones.

The

skull of Edmontosaurus in general was long and

triangular, with the

largest known complete skull being up to one hundred and eighteen

centimetres long. Like other hadrosaurs, the front of the mouth

would have had an additional covering of a keratinous beak. Usually

keratin does not get preserved, but at least one specimen of

Edmontosaurus has been so well preserved that we can

measure that the

keratin of the beak would have extended for at least eight centimetres

in front of the mouth.

The

overall form of the skull would change with age, with adults that had

proportionately flatter and longer skulls than juveniles. This change

in age is partially what contributed to some Edmontosaurus

specimens

being named as other species and genera, but when palaeontologists

realised the age changes, the names were re-classified as synonyms to

Edmontosaurus.

Many

Edmontosaurus skulls are so well preserved that it

has been possible

for some researchers to make casts of the brain cavity. Relative to

body size, the brain of Edmontosaurus was small

in proportion, and

elongate in form. Edmontosaurus are not expected

to have been

exceptionally intelligent since most of the brain was orientated

towards primal functions such as sight and smell, but they were

probably intelligent enough to survive on the landscape of late

Cretaceous North America.

The

teeth in the skull were arranged in the form of dental batteries in the

posterior region of the mouth. The method of feeding for

Edmontosaurus (and other hadrosaurs) is thought

to have been along

the lines of plants being cropped by the keratinous beak, and then

ground by the teeth at the back. As in all dinosaurs, when these

teeth became worn and lost, new teeth would erupt to replace them.

A 2009 study by Williams et al studied the micro wear patterns on

the teeth and concluded that Edmontosaurus were

probably grazers as

opposed to selective browsers.

As

far as the rest of the body is concerned, Edmontosaurus

were quite

generic in their appearance. The centre of balance in the body would

have been just in front of the hips, with the large rear legs serving

the focus of the weight bearing function. Because of the developed

rear legs, it certainly would have been possible for Edmontosaurus

to

adopt a bipedal posture, however they mostly seem to have been

bipedal. The main evidence for this comes from the simple observation

of the fore limbs which although are not as well developed as the rear

limbs, are still formed for a weight bearing function. Fossil

track ways of hadrosaurs also show that these kinds of dinosaurs walked

about on all fours, and not just their rear legs.

Much

analysis has been done upon how Edmontosaurus

moved, with the 2009

study by Sellers et al being one of the better known. Hadrosaurs

like Edmontosaurus were long thought to by earlier

palaeontologists to

have tried to escape from predators by running on their hind legs,

but computer modelling from that study revealed that Edmontosaurus

would have likely been faster if moving on all fours in the form of a

gallop rather than running on just the rear legs.

As

in other hadrosaurs, the tail vertebrae in the tail of Edmontosaurus

were reinforced by a lattice network of tendons that became ossified

with age. This means that the tail would have been quite rigid and

not open to much movement save for at the base. Such a tail is

speculated to have primarily been as a counterbalance, particularly

when changing between quadrupedal and bipedal postures. Another

function of the tail may have been as a display feature, perhaps

being differently coloured than the rest of the body, though we

cannot know this for certain at this time.

Preserved

skin impressions have revealed that Edmontosaurus

had non overlapping

scales, most of which were small at being between one and three

millimetres across. Larger polygonal scales ranging from below five

to up to ten millimetres across are known to have been on areas such as

the fore arms and shoulder. The smaller scales were more typical of

the flanks while scales got slightly larger further up and down the

body. There also seems to have been a frilly ridge of soft tissue

that ran down the centreline of the neck and back. Preserved segments

of this frill were about five centimetres long and about eight

centimetres high.

It

used to be that how big an Edmontosaurus was

depending upon which

species you were talking about. The type species E.

regalis has

been considered to have been the larger with individuals reaching nine

meters at adulthood with the oldest individuals reaching twelve and

potentially even thirteen meters in length. The second species E.

annectens has often been credited as being much smaller at

about eight

to nine meters long, however new studies of existing Edmontosaurus

material has now revealed that E. annectens may

have actually reached

sizes up to twelve meters long as well. This would mean that E.

anenctens was actually comparable to E.

regalis in terms of size

after all.

In

terms of behaviour Edmontosaurus have been

perceived to be herding

animals based largely upon the evidence of bone beds of Edmontosaurus

individuals collected together, ranging from a few, to many

thousands of individuals. Herding would make sense for a plant eating

animal to survive, especially an animal that lived on a landscape

which included predators as large as itself, particularly

tyrannosaurs

such as Albertosaurus,

Daspletosaurus

and of course

Tyrannosaurus

itself.

There

is also strong evidence to suggest that Edmontosaurus

were frequently

targeted and eaten by the predators of the North American late

Cretaceous. Tyrannosaur tooth marks from Albertosaurus

and

Daspletosaurus are known upon Edmontosaurus

fossils, though these can

be perceived as signs of scavenging. Teeth marks from smaller

theropod dinosaurs are also known upon the jaws of Edmontosaurus,

suggesting that the neck may have been the preferred vulnerable spot

targeted by such predators.

The

most exciting discovery showing predator prey interaction though can be

seen upon the damaged caudal vertebrae of a mounted Edmontosaurus

specimen that is on display at the Denver Museum of Nature and

Science. Some of the vertebrae on this specimen have been bitten into

by a large predatory theropod with a bite pattern similar to what you

would expect from a tyrannosaur. In addition to this the only large

theropod that is known to have existed in the same formation as this

individual Edmontosaurus and also to have been

big enough to reach

high enough to inflict such a bite is Tyrannosaurus.

What

is really astonishing about this individual Edmontosaurus

is that after

the bite was inflicted, the bone started to heal, indicating that

the attack was not immediately successful in killing it, and that the

individual survived for long enough for the bone to partially heal.

This proves that this Edmontosaurus was alive at

the time of the

attack and therefore it cannot be a case of scavenging. Further study

of the specimen by renowned palaeontologist Kenneth Carpenter has also

revealed that the left hip also has a partially healed fracture from an

injury that likely happened before the attack that resulted in the tail

injury. This may mean that the when this individual Edmontosaurus

was

attacked, it may have had a slight limp which resulted in it being

targeted by a tyrannosaur.

Edmontosaurus

is known to have had one of the broadest geographical distributions of

all the known hadrosaurs, something that a 2008 study by Bell and

Snively considered to have been the result of migratory behaviour.

Migratory behaviour may have also been possible considering that if

Edmontosaurus did live in groups, they may have

had to continually

move to avoid exhausting available food resources. In addition the

occurrence of vast bone beds may have been caused by many Edmontosaurus

drowning together as they tried to cross rivers swollen with flood

water, as has been proposed for other types of dinosaur such as

ceratopsians.

However

there are doubts as to whether Edmontosaurus were

truly migratory,

potentially moving many hundreds if not thousands of miles with the

seasonal growth of plants, or if they instead did not roam as far.

One study by Chisamy et al in 2012, revealed that hadrosaur

remains recovered from what were more polar regions, were from

populations that lived there all the time rather than from a migratory

population. Perhaps a more general scenario would be that as with

most animals, Edmontosaurus stayed where the food

was, only moving

on to the next horizon for food when they had to.

Further reading

- Supplement to the synopsis of the extinct Batrachia and Reptilia of

North America - American Philosophical Society, Proceedings 12 (86):

41–52. - Edward Drinker Cope - 1871.

- Report on the vertebrate paleontology of Colorado - U.S. Geological

and Geographical Survey of the Territories Annual Report 2: 429–454. -

Edward Drinker Cope - 1874.

- Report on the stratigraphy and Pliocene vertebrate paleontology of

northern Colorado - U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the

Territories Annual Report 1: 9–28. - Edward Drinker Cope - 1874.

- On the characters of the skull in the Hadrosauridae - Proceedings of

the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences 35: 97–107. - Edward

Drinker Cope - 1883.

- The genus and species of the Trachodontidae (Hadrosauridae,

Claosauridae) Marsh - Annals of the Carnegie Museum 1 (14): 377–386.

John B. Hatcher - 1902.

- The dinosaur Trachodon annectens - Smithsonian

Miscellaneous

Collections 45: 317–320 - Frederic A. Lucas - 1904.

- The epidermis of an iguanodont dinosaur - Science 29 (750): 793–795.

- Henry Fairfield Osborn - 1909.

- Integument of the iguanodont dinosaur Trachodon -

Memoirs of the

American Museum of Natural History 1: 33–54 - Henry Fairfield Osborn -

1912.

- The manus in a specimen of Trachodon from the

Edmonton Formation of

Alberta - The Ottawa Naturalist 27: 21–25. - Lawrence M. Lambe - 1913.

- On the fore-limb of a carnivorous dinosaur from the Belly River

Formation of Alberta, and a new genus of Ceratopsia from the same

horizon, with remarks on the integument of some Cretaceous herbivorous

dinosaurs - The Ottawa Naturalist 27: 129–135. - Lawrence M. Lambe -

1914.

- On the genus Trachodon - Science 41 (1061):

658–660 - Charles W.

Gilmore - 1915.

- A new genus and species of crestless hadrosaur from the Edmonton

Formation of Alberta. - The Ottawa Naturalist 31 (7): 65–73. - Lawrence

M. Lambe - 1917.

- The hadrosaur Edmontosaurus from the Upper

Cretaceous of Alberta.

Memoir 120. - Department of Mines, Geological Survey of Canada. pp.

1–79. - Lawrence M. Lambe - 1920.

- A new species of hadrosaurian dinosaur from the Edmonton Formation

(Cretaceous) of Alberta. Bulletin 38. - Department of Mines, Geological

Survey of Canada. pp. 13–26. - Charles W. Gilmore - 1924.

- Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America. Geological Society of

America Special Paper 40. - Geological Society of America. - Richard

Swann Lull & Nelda E. Wright - 1942.

- A reconsideration of the paleoecology of the hadrosaurian dinosaurs -

American Journal of Science 262 (8): 975–997. - John H. Ostrom - 1964.

- The posture of hadrosaurian dinosaurs - Journal of Paleontology 44

(3): 464–473. - Peter M. Galton - 1970.

- Hadrosaurian dinosaur bills — morphology and function - Contributions

in Science (Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History) 193: 1–14. -

William J. Morris - 1970.

- The evolution of cranial display structures in hadrosaurian dinosaurs

- Paleobiology 1 (1): 21–43. - James A. Hopson - 1975.

- A "segmented" epidermal frill in a species of hadrosaurian dinosaur -

Journal of Paleontology 58 (1): 270–271. - John R. Horner - 1984.

- Evidence of predatory behavior by theropod dinosaurs - Gaia 15:

135–144. - Kenneth Carpenter - 1998/2000.

- Taphonomic aspects of theropod tooth-marked bones from an

Edmontosaurus bone bed (Lower Maastrichtian),

Alberta, Canada - Journal

of Vertebrate Paleontology 19 - Aase Roland Jacobson, Michael J. Ryan -

2000.

- Dinosaur forebrains - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 21 (3,

Suppl.): 64A - Harry J. Jerison, John R.Horner& Celeste C.

Horner - 2001.

- New skin structures from a juvenile Edmontosaurus

from the Late

Cretaceous of North Dakota - Abstracts with Programs — Geological

Society of America 35 (2): 13. - Tyler R. Lyson, Douglas H. Hanks

& Emily S. Tremain - 2003.

- An allometric study comparing metatarsal IIs in Edmontosaurus

from a

low-diversity hadrosaur bone bed in Corson Co., SD - Journal of

Vertebrate Paleontology 23 (3, suppl.): 56A–57A. - Rebecca Gould, Robb

Larson & Ron Nellermoe - 2003.

- Microscale δ18O and δ13C isotopic analysis of an ontogenetic series

of the hadrosaurid dinosaur Edmontosaurus:

implications for physiology

and ecology - Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, and Palaeoecology 206

(2004): 257–287 - Kathryn J. Stanton Thomas & Sandra J. Carlson

- 2004.

- Preliminary depositional model for an Upper Cretaceous Edmontosaurus

bonebed - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26 (3, suppl.): 49A.,

Arthur Chadwick, Lee Spencer & Larry Turner 2006.

- How to make a fossil: part 2 – Dinosaur mummies and other soft

tissue. - The Journal of Paleontological Sciences. - Kenneth Carpenter

- 2007.

- A three-dimensional animation model of Edmontosaurus

(Hadrosauridae)

for testing chewing hypotheses - Palaeontologia Electronica 11 (2) -

Natalia Rybczynski, Alex Tirabasso, Paul Bloskie, Robin Cuthbertson,

Casey Holliday - 2008.

- Polar dinosaurs on parade: a review of dinosaur migration -

Alcheringa 32 (3): 271–284. - Phil R. Bell & E. Snively - 2008.

- Cranial kinesis in dinosaurs: intracranial joints, protractor

muscles, and their significance for cranial evolution and function in

diapsids - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28 (4): 1073–1088. -

Casey M. Holliday & Lawrence M. Witmer - 2008.

- Mineralized soft-tissue structure and chemistry in a mummified

hadrosaur from the Hell Creek Formation, North Dakota (USA) -

Proceedings of the Royal Society B 276 (1672): 3429–3437 - Phillip L.

Manning, Peter M. Morris, Adam McMahon, Emrys Jones, Andy Gize, Joe H.

S.Macquaker, G. Wolff, Anu Thompson, Jim Marshall, Kevin G. Taylor,

Tyler Lyson, Simon Gaskell, Onrapak Reamtong, William I. Sellers, Bart

E. van Dongen, Mike Buckley, Roy A. Wogelius - 2009.

- Cranial variation in Edmontosaurus

(Hadrosauridae) from the Late

Cretaceous of North America - North American Paleontological Convention

(NAPC 2009): Abstracts, p. 95a. - N. E. Campione - 2009.

- Virtual palaeontology: gait reconstruction of extinct vertebrates

using high performance computing -Palaeontologia Electronica 12 (3). -

W. I. Sellers, P. L. Manning, T. Lyson, K. Stevens & L.

Margetts - 2009.

- Quantitative analysis of dental microwear in hadrosaurid dinosaurs,

and the implications for hypotheses of jaw mechanics and feeding -

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (27): 11194–11199.

- Vincent S. Williams, Paul M. Barrett & Mark A. Purnell - 2009.

- Cranial Growth and Variation in Edmontosaurs (Dinosauria:

Hadrosauridae): Implications for Latest Cretaceous Megaherbivore

Diversity in North America. - PLoS ONE, 6(9): e25186 - N. E. Campione

& D. C. Evans - 2011.

- Complex dental structure and wear biomechanics in hadrosaurid

dinosaurs - Science 338 (6103): 98–101 - Gregory M. Erickson, Brandon

A. Krick, Matthew Hamilton, Gerald R. Bourne, Mark A. Norell, Erica

Lilleodden & W. Gregory Sawyer - 2012.

- Kinetic limitations of intracranial joints in Brachylophosaurus

canadensis and Edmontosaurus regalis

(Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae), and

their implications for the chewing mechanics of hadrosaurids - The

Anatomical Record 295 (6): 968–979. - Robin S. Cuthbertson, Alex

Tirabasso, Natalia Rybczynski & Robert B. Holmes - 2012.

- Hadrosaurs were perennial polar residents - The Anatomical Record:

Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology. - A.

Chinsamy, D. B. Thomas, A. R. Tumarkin-Deratzian & A. R.

Fiorillo - 2012.

- A Mummified Duck-Billed Dinosaur with a Soft-Tissue Cock's Comb -

Current Biology. - Phil R. Bell, Federico Fanti, Philip J. Currie

& Victoria M. Arbour - 2013.

- Supplementary cranial description of the types of Edmontosaurus

regalis (Ornithischia: Hadrosauridae), with comments on the

phylogenetics and biogeography of Hadrosaurinae. - PLOS ONE. 12 (4). -

H. Xing, J. C. Mallion & M. L. Currie - 2017.

Skeletal Trauma with Implications for Intratail Mobility in

Edmontosaurus annectens from a Monodominant Bonebed, Lance Formation

(Maastrichtian), Wyoming USA. - PALAIOS. 35 (4): 201–214 - Bethania C.

T. Siviero, Elizabeth Rega, William K. Hayes, Allen M. Cooper, Leonard

R. Brand & Art V. Chadwick - 2020.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|