Lambeosaurus

Name:

Lambeosaurus

(Lambe’s lizard - after the palaeontologist Lawrence Morris

Lambe).

Phonetic: Lam-be-o-sore-us.

Named By: William Parks - 1923.

Synonyms: Corythosaurus frontalis,

Didanodon, Procheneosaurus praeceps, Tetragonosaurus.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria,

Ornithischia, Ornithopoda, Hadrosauridae, Lambeosaurinae,

Lambeosaurini.

Species: L. lambei (type),

L. magnicristatus. Possibly also L.

paucidens, though this species is not accepted by all.

Diet: Herbivore.

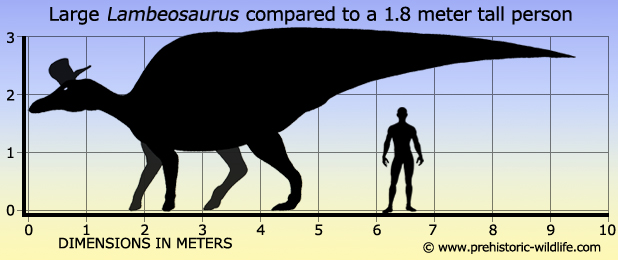

Size: Around 9 to 9.5 meters long.

Known locations: Canada - Alberta. USA -

Montana. Possibly also Baja California.

Time period: Campanian of the Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: Multiple specimens including

some juveniles.

Lambeosaurus

the dinosaur

Lambeosaurus

is one of the hadrosaurs

that is frequently depicted in dinosaur books

and toys, and study of this genus is required learning for anyone who

wishes to know more about the hadrosaurs in general.

Lambeosaurus

is best known from Canada and upper Montana USA, although other

attributed fossils in the past have suggested that Lambeosaurus

had a

significantly broader range. The most distinctive feature of

Lambeosaurus is the crest which is often described

as being either

hatchet or axe shaped, the broader forward portion being the blade

while the thin rearward projection is the handle. This rear

projection is solid; however the forward portion is hollow with a

network of passages inside (a signature feature of the lambeosaurine

hadrosaurids).

The

function of the crest is one of the most often talked about areas of

the body. One explanation is that the crest was used as either a

snorkel or an air chamber for trapping a supply of breathable air so

that Lambeosaurus could hold their heads underwater

for extended

periods. This however would require Lambeosaurus

to regularly be

active within bodies of water, and it does not explain the variance

in form of head crests between Lambeosaurus and

other lambeosaurine

genera.

One

exciting theory is that the crests allowed for the storage of salt

glands, special organs that allow excess salt from the environments

to be excreted. However the presence of salt glands is usually

associated with animals that live in marine (saltwater) ecosystems

which have higher levels of salts, thus necessitating the presence of

salt glands. This is not actually that much of a stretch to believe

however since during the late Cretaceous most of central North America

was submerged by a shallow sea called the Western Interior Seaway

that ran North to South from what is now Upper Canada into the Gulf of

Mexico. The areas that Lambeosaurus remains are

known from have been

interpreted as being marshes and swamps that were in close proximity to

the coastline of the Western Interior Sea. Additionally a 1979

paper by palaeontologist Jack R. Horner described what appeared to

be Lambeosaurus jaws (L.

magnicristatus) from marine sediment.

The problems with this theory however is that it is that with this

evidence it is only relevant to Lambeosaurus,

with many other

hadrosaurs being known from different ecosystems. Additionally this

does not explain the difference in crest form between not only

hadrosaur genera, but the two main Lambeosaurus

species.

The

only theory that explains the different crest forms is that of

display. Firstly different species of Lambeosaurus

would be able to

tell each other apart by the different form of head crest, as well as

any hadrosaurid other genera that were active in the same locations as

they were. Additionally the crests of adult Lambeosaurus

were more

developed than juveniles which indicates that they were also a sign of

maturity. Specimens thought to be females also have more rounded

crests than the males.

Another

factor concerning display is that of sound. The forward portion of

the crest is hollow with a network of tubes, and assuming this is not

just a weight saving feature to reduce stress on the head and neck,

this may have formed a resonating chamber for amplifying the calls.

Not only have studies continually revisited this area, but different

crest variations between species should allow for different sounding

calls. Study in one specimen of the related Corythosaurus

also

suggests that lambeosaurine hadrosaurids in particular had very good

hearing, further supporting the auditory hypothesis for the crest.

Size

estimates for Lambeosaurus can vary greatly

depending upon source

because of the large amounts of fossil remains that have been

attributed to the genus. The confirmed Lambeosaurus

remains that are

known from Alberta Canada and Montana, USA point to individuals

around the nine to nine and a half meter mark for total length. Upper

estimates of fifteen meters long still exist in some sources however,

though this estimate is based upon material that is no longer

attributed to the Lambeosaurus genus. This

stems back to the

description of a dubious species of Lambeosaurus

in 1981 called

L. laticaudus from fossils found in Baja

California. The

Lambeosaurus connection however could never be

confirmed since the

crest is missing. In 2012 these remains were re-established as a

new genus called Magnapaulia.

As

with all hadrosaurids, Lambeosaurus seems to have

been primarily

quadrupedal with the ability to balance and possibly walk on just the

rear legs when it had to. Out of the original five digits of the

fore-arm hand, the first digit is missing, lost through selective

evolutionary factors. Digits two, three and four are developed into

weight bearing hooves, and when combined with footprints of other

hadrosaurids, confirms the idea that Lambeosaurus,

and other

hadrosaurids, were mostly bipedal. The fifth digit is free from the

others and may have been to help grip and/or balance when the body

weight was shifted forward.

By

being both quadrupedal and occasionally bipedal, Lambeosaurus

could

browse upon anything from low to moderately high growing vegetation.

The anterior portion of the mouth however is narrower than in many

other hadrosaurids, something that suggests that Lambeosaurus

were

more selective in their browsing habits. Once food was removed from

the main plant, it was then processed by the grinding teeth that were

arranged in batteries at the back of the mouth.

Lambeosaurus

possibly shared its habitat with other genera of hadrosaur such as

Corythosaurus, though this genus is currently

known from slightly

older Campanian deposits, which indicates that Lambeosaurus

may have

actually replaced Corythosaurus. Other dinosaurs

roughly active

around that time and locale include the ceratopsians

Chasmosaurus

and

Centrosaurus,

the nodosaur Edmontonia

as well as the ankylosaur

Euoplocephalus.

However the exact relationships between these

different dinosaurs is still being established since some such as

ankylosaurs seem to have been better adapted to dryer more arid

environments due to the arrangements of their nasal passages.

Predators of Lambeosaurus may have included

Campanian era tyrannosaurs

such as Albertosaurus

and Daspletosaurus.

Classification history of

Lambeosaurus

The

history of Lambeosaurus is one that is steeped in

the misinterpretation

of dinosaur fossils at a time when palaeontology as we know it today

was still in its infancy. The first Lambeosaurus

remains were

described by Lawrence Lambe in 1902, however these fossils were

only of partial post cranial remains, and rather than establish them

as a new genus, Lambe assigned them as a species of Trachodon,

T.

marginatus. The problem here is that Trachodon

has always been a

very dubious genus. Back in 1856 another palaeontologist named

Joseph Leidy created the Trachodon dinosaur genus

based only upon the

description of a collection of teeth. Today we now know this

description to be flawed since the teeth assigned to Trachodon

are

actually a combination of both hadrosaur and ceratopsian teeth, two

distantly related yet very different groups of dinosaurs. Leidy named

many genera of prehistoric animals many from only teeth and some like

Aublysodon

remain very dubious, while others have been cast down as

valid genera. But Leidy did achieve one very big success from only

describing teeth with his naming of Troodon

in 1856.

The

dubious nature of Trachodon seems to have still

been appreciated by

Lambe since when he described two new skulls in 1914 that he

thought belonged to T. marginatus he created the

genus

Stephanosaurus. The problem here is the same as

many extinct animals

that have their initial descriptions based upon very incomplete

remains. The fossils originally described as T. marginatus

were of

the post cranial skeleton with no elements of the skull. The original

concept of the skulls being placed with this material is based around

the fact that the skulls came from roughly the same area as the T.

marginatus fossils. This makes the assumptions that they

belong to

the same genus possible, but one that is impossible to establish

without a set of remains that bridge the gaps between both groups of

fossils (i.e., skull and post cranial fossils of one individual

that can be compared to existing fossils assigned to the genus).

This is why in 1923 William parks removed the skulls from

Stephanosaurus (today regarded as a dubious

genus) and redescribed

them as a new genus, Lambeosaurus, in honour of

Lawrence Lambe who

had died four years earlier in 1919.

For

many years Lambeosaurus (including its earlier

association with

Stephanosaurus) was not known to have very many

fossils. Today

however we now know that that was never the case, further

Lambeosaurus were actually being discovered in the

early years of the

twentieth century. In 1917 a new dinosaur called Cheneosaurus

was

named by Lawrence Lambe, a dinosaur that would become the type genus

of the Cheneosaurinae, a group of dinosaurs that resembled

hadrosaurs, but were much smaller.

Before

this in 1902, Henry Fairfield Osborn named a genus Didanodon

altidens based upon a partial left jaw. Lambe later

re-classed this

specimen as a species of Trachodon, T.

altidens. In 1920

William Diller Matthew took a photograph of the skeletal remains of

one such dinosaur and named it Procheneosaurus;

however this is not

the usual method for establishing a new genus. When William parks

described the genus Tetragonosaurus from other

fossils recovered from

the Dinosaur Park Formation, he also included the fossils of

Procheneosaurus into the type species of Tetragonosaurus,

T.

praeceps (A second species of T. erectofrons

was

established for

smaller specimens). The Tetragonosaurus genus

would grow further

with the addition of T. cranibrevis by Charles

M. Sternberg in

1935.

However,

nearly forty years’ worth of classification was turned on its head

in 1942 when Richard Swann Lull and Nelda Wright released a

detailed study about these and associated dinosaurs. In this study

they declared that the whole Tetragonosaurus genus

should actually be

called Procheneosaurus, as well as possibly Trachodon

altidens too.

The really ground breaking discovery however would come in 1975

when Peter Dodson demonstrated that the cheneosaurs were actually made

up of the juveniles of the larger hadrosaurs. Specifically the type

specimen of what was now Procheneosaurus was seen

to now be a juvenile

Lambeosaurus, while other specimens were probably

juveniles of

Corythosaurus.

The

problem here is that technically Procheneosaurus

was named before

Lambeosaurus, and usually the older name takes

precedence over any

future naming. Despite this Lambeosaurus is still

credited as being

the specific genus for these remains with Procheneosaurus

being treated

as a synonym. Another case of a dinosaur retaining a second name

despite having fossils attributed to an earlier description of another

genus is that of Tyrannosaurus.

Today

Lambeosaurus is best known for being the type genus

of the

Lambeosaurinae, one of the two largest groups of hadrosaurs.

Members of this group, referred to as lambeosaurines, all exhibit

hollow head crests, though the physical form of the crest can vary

greatly between different genera. Other lambeosaurine genera closely

related to Lambeosaurus include Olorotitan,

Corythosaurus and

Hypacrosaurus.

Corythosaurus in particular is very similar in

physical form to Lambeosaurus, so much so that

the only obvious

differences between them is the shape and form of the crest and how it

attaches to the skull.

There

were once seven species of Lambeosaurus, but at

the time of writing

only the type species L. lambei and L.

magnicristatus are

universally considered to be valid. Both of these species are known

from upper North America and can be distinguished on the basis of

different crest form. L. lambei has a rear bony

projection that is

roughly the same length as the forward crest, while L.

magnicristatus has a reduced bony projection and a slightly

enlarged

forward crest. Another species called L. paucidens

is only known

from post cranial remains so it is hard to be certain how or even if it

is related to the other two Lambeosaurus species.

With this in mind,

many palaeontologists consider these remains to instead be a species

of Hadrosaurus

(H. paucidens).

Other past species have since

been established to be different sexes of existing hadrosaur genera,

while others (such as L. laticaudus stated

above) are now

different genera.

Further reading

- Corythosaurus intermedius, a new species of

trachodont dinosaur,

William A. Parks - 1923.

- A new genus and two new species of trachodont dinosaurs from the

Belly River Formation of Alberta, William A. Parks - 1931.

- New species of trachodont dinosaurs from the Cretaceous formations

of Alberta, William A. Parks - 1931.

- Taxonomic implications of relative growth in lambeosaurine

dinosaurs, Peter Dodson - 1975.

- Upper Cretaceous dinosaurs from the Bearpaw Shale (marine) of

south-central Montana with a checklist of Upper Cretaceous dinosaur

remains from marine sediments in North America, Jack R. Horner -

1979.

- A new species of hadrosaurian dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of

Baja California: ?Lambeosaurus laticaudus,

William J. Morris -

1981.

- Acoustic analyses of potential vocalization in lambeosaurine

dinosaurs, David B. Weishampel - 1981.

- Anatomy and relationships of Lambeosaurus magnicristatus,

a

crested hadrosaurid dinosaur (Ornithischia) from the Dinosaur Park

Formation, Alberta, David C. Evans & Robert R. Reisz

- 2007.

Random favourites

|

|

|