Ornithomimus

Name:

Ornithomimus

(Bird mimic).

Phonetic: Or-nif-oh-mime-us.

Named By: Othniel Charles Marsh - 1890.

Synonyms: Dromiceiomimus.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria,

Saurischia, Theropoda, Ornithomimidae, Ornithomiminae.

Species: O. velox (type),

O.

edmontonicus. Many other species have been named in the

past, but most of these are considered dubious and/or have been

assigned to other existing species and genera.

Diet: Possible omnivore.

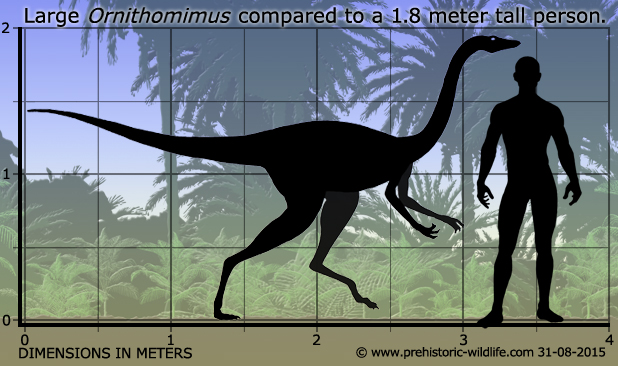

Size: Exact size depends upon the species in

question. Larger individuals approximately 3.8 meters long.

Known locations: USA and Canada.

Time period: Campanian to Maastrichtian of the

Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: Many individuals, but often

incomplete.

Named

in 1890 from a partial hand and foot, Ornithomimus

became the

first known ornithomimid,

which is why it is considered the type

genus of the Ornithomimidae. The ornithomimds (also sometimes

called 'ostrich dinosaurs’) were small dinosaurs that usually

ranged between three and four meters long, although some were

slightly larger. During the late Cretaceous ornithomimds seem to have

been particularly widespread across North America and Asia where they

relied upon speed for survival in habitats that were dominated by

tyrannosaurs, and shared with horned and armoured dinosaurs like

ceratopsians and ankylosaurs.

Amongst

the dinosaurs Ornithomimus has one of the most

complicated taxonomic

histories that continue to cause much confusion amongst researchers.

In a nut shell, because it was one of the first ornithomimds

discovered, Ornithomimus along with Struthiomimus

were effectively

used as wastebasket taxons where any remains remotely resembling the

earlier material were almost automatically attributed to one of these

genera as a new species. This also happened for the first two

dinosaur genera ever named, Megalosaurus

and Iguanodon,

although

perhaps a better analogy would come from the pterosaurs Pterodactylus

and Rhamphorhynchus.

Both of these genera once had an incredible

number of species attributed to them, just for most of them to be

found to be the same as the type species or actually different genera

completely.

The

classification of Ornithomimus didn’t really get

under way properly

until 1972 when palaeontologist Dale Russel undertook a review of

the ornithomimids. The result of Russel’s study was that Ornithomimus

along with Struthiomimus were each themselves valid

genera and that

Ornithomimus had two distinct species, O.

velox and O.

edmontonicus, even though the line between these two

species was

occasionally blurry. Russel additionally created two new ornithomimid

genera of Archaeornithomimus

and Dromiceiomimus on

the basis that some

Ornithomimus remains could not be placed with

the genus.

Other

palaeontologists have continued to study Ornithomimus

and other closely

related genera, but results and conclusions have been mixed between

different researchers. Further species have been named only to be

contested by others who claim there is not enough difference.

Additionally the earlier creation of Dromiceiomimus

is now seen as

invalid and this genus is now usually attributed as a synonym to

Ornithomimus where the fossil material originally

belonged. It is

hard to say for certain what the future holds for Ornithomimus,

although its place a valid genus is not in dispute. Further remains

and study however may yet bring a change in the number of valid species.

It

is actually a lot easier to talk about Ornithomimus

as a dinosaur

rather than its taxonomic history. Like with all other

ornithomimids, Ornithomimus is noted for having

long legs, the

lower portions of which were considerably longer than the femur. This

is a sure sign that Ornithomimus was a dinosaur

that was built for

speed and with the exception of other ornithomimids, was probably the

fastest dinosaur in its ecosystem. This speed would have probably

been enough to keep it out of the way of big predators like

Tyrannosaurus

and Albertosaurus,

although it would be interesting to

see how Ornithomimus faired against smaller and

faster predatory

dinosaurs, including juveniles of the big tyrannosaurs. To help

reduce weight the bones of Ornithomimus, like

other ornithomimids,

were hollow. Another adaptation to fast running is the tail which in

life would have been carried off the ground and supported with tendons

so that it could be used as a stiff balancing aid.

The

obvious tactic for a predator to employ against a fast animal like

Ornithomimus would be ambush, dashing out from

cover and closing the

gap between themselves and their target before the prey could turn and

use their speed to escape. This was not all that easy to do either

however, as Ornithomimus had a head that was

carried high from the

body by a long neck. This meant that Ornithomimus

could see over

cover and see other dinosaurs approaching from a long way off which

would make sneaking up on one very difficult. The large orbital

fenestrae of the skull also suggest proportionately larger eyes to fit

within them. This indicates that Ornithomimus

would have had keen

vision, possibly even for seeing at night. Analysis of sceleral

rings has indicated a cathemeral lifestyle, which means that

Ornithomimus would have been active for short

periods during both the

day and night time hours.

Another

feature of the skull is the enlarged brain cavity that also suggests

that Ornithomimus had a large and well developed

brain for its size.

Although it is tempting to say that this may have made Ornithomimus

an

intelligent dinosaur, it is not so much the case of how big the brain

is as a whole, but the development of certain parts. The

development of the brain in Ornithomimus is usually

taken as being

towards proprioception, or in simple terms better control over the

body and its movements. This is a very logical conclusion when you

think that a bipedal dinosaur that was capable of breaking the speed

limit on some of our roads would need excellent coordination when

running over rough terrain while being chased by a predator.

Rather

than having more typical jaws with teeth, Ornithomimus

actually had a

mouth that was more like a beak which could have been used for a

variety of feeding styles. As a theropod Ornithomimus

is thought to

have descended from carnivorous ancestors, but it is still uncertain

if it ate meat as well. The beak-like mouth could have been used to

selectively browse certain parts of plants, or alternatively

Ornithomimus could have used it to pick up insects.

Ornithomimus may

have also preyed upon small animals like lizards and primitive mammals

that it may have caught by using its long neck to reach into the

undergrowth. It is also possible that all of the above might be

correct and that Ornithomimus was an omnivore which

browsed the

landscape eating whatever it could find and thereby not competing with

other more specialised groups of dinosaurs. Regardless of what it

ate, the lack of teeth would at least suggest that Ornithomimus

swallowed food whole.

The

arms of Ornithomimus are also quite long with long

fingers to match.

It has been suggested that these long arms were used to reach out and

grab branches in the same way that a sloth feeds, although it’s

uncertain how much benefit if any Ornithomimus

would have gained from

this because it already had a long relatively long neck for this

purpose already. It’s possible that the long arms and hands may have

played a bigger part in prey capture, since the mouth lacked teeth to

grip hold of prey. If Ornithomimus raided nests

for eggs as has been

suggested in the past, then it may have held onto eggs within its

hands while the beak-like mouth broke the shell and dipped into the

yolk within.

One

area where Ornithomimus differs from other

ornithomimids is that it had

a shorter actual body length. This may indicate an adaptation for

greater agility in this genus as a shorter bodied animal would be able

to make tighter turns than a longer bodied animal. Another area of

study now concerning Ornithomimus is if it actually

had hair like

feathers over its body. For a long time there was no evidence to

directly support the idea for feathers on Ornithomimus,

but new

specimens and studies of Ornithomimus are

increasingly suggesting that

Ornithomimus, and perhaps most if not all

ornithomimid dinosaurs

actually had feathers. These feathers seem to have been small and

pernaceous meaning that they were not suited to flight and served more

of an insulatory version. Feather data for Ornithomimus

is still in

its early stages, but Ornithomimus seems to have

mostly feathers upon

the body, tail and neck. No feathers seem to have been present

upon the legs.

Further reading

- Description of new dinosaurian reptiles. - The American Journal of

Science, series 3 39:81-86. - Othniel Charles Marsh - 1890.

- Notice of new reptiles from the Laramie Formation. - American Journal

of Science 43:449-453. - Othniel Charles Marsh - 1892.

- A new Ornithomimus with complete abdominal

cuirass. - The Canadian

Field-Naturalist 47(5): 79-83. - C. M. Sternberg - 1933.

- A specimen of Ornithomimus velox (Theropoda,

Ornithomimidae) from the

terminal Cretaceous Kaiparowits Formation of southern Utah. - Journal

of Paleontology, 59(5): 1091-1099. - DeCourtean & Russel - 1985.

- A juvenile Ornithomimus antiquus (Dinosauria:

Theropoda:

Ornithomimosauria), from the Upper Cretaceous Kirtland Formation

(De-na-zin Member), San Juan Basin, New Mexico. - New Mexico Geological

Society Guidebook, 48th Field Conference, Mesozoic Geology and

Paleontology of the Four Corners Region. 249-254. - Sullivan - 1997.

- A reevaluation of the genus Ornithomimus based on

new preparation of

the holotype of O. velox and new fossil

discoveries. - Journal of

Vertebrate Paleontology. - L. Claessens, M. Loewen & Z.

Lavender - 2011.

- A redescription of Ornithomimus velox Marsh, 1890 (Dinosauria,

Theropoda). - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. - Leon P. A. M.

Claessens & Mark A. Loewen - 2015.

- A densely feathered ornithomimid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the

Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, Canada". Cretaceous

Research. 58: 108–117. - Aaron J.van der Reest, Alexander P.Wolfe

& Philip J.Currie - 2016.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|