Rhamphorhynchus

Name:

Rhamphorhynchus

(Beak Snout).

Phonetic: Ram-foe-rink-us.

Named By: Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer -

1846.

Synonyms: Odontorhynchus longicaudus,

Ornithocephalus muensteri, O. longicaudus, O. lavateri,O.

gemmingi, O. giganteus, O. grandis, O. secundarius,

Pterodactylus muensteri, P. longicaudus, P. lavateri, P.

gemmingi, P. lavateri, P. hirundinaceus, P.

hirundinaceus, P. giganteus, P. grandis, Pteromonodactylus

phyllurus, Rhamphorhynchus longicaudus, R. gemmingi, R.

suevicus, R. hirundinaceus, R. curtimanus, R. longimanus,

R. meyeri, R. phyllurus, R. longiceps, R. grandis, R.

kokeni, R. megadactylus, R. carnegiei.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia,

Pterosauria, Rhamphorhynchidae, Rhamphorhynchinae.

Species: R. longicaudus (type),

R. etchesi, R. muensteri.

Type: Piscivore/Insectivore.

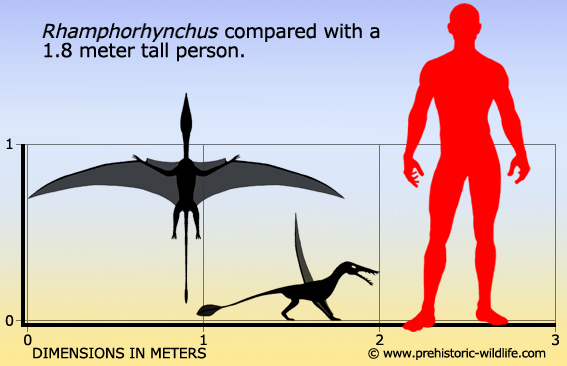

Size: 1.81 meter wingspan, 1.26 meters long.

Known locations: Germany, Portugal, Tanzania.

Time period: Oxfordian to Kimmeridgian of the

Jurassic.

Fossil representation: Dozens of individuals, some

including impressions of soft tissue.

Rhamphorhynchus

is one of the classic pterosaurs

that have been known to science since

the early days of palaeontology. It had what appears to have been a

sizeable distribution and aside from the above locations,

Rhamphorhynchus specimens have also been attributed

to other European

countries like the United Kingdom. Unfortunately however, these

specimens are sometimes no more than fossilised teeth.

The

best preserved and most numerous examples hail from Germany where

Rhamphorhynchus was first discovered. Not only do

these remains

include complete specimens, but also impressions of the wings,

revealing their placement and texture. Specimens also display

potential dimorphism between males and females.

The

jaws of Rhamphorhynchus are filled with sharp

needle like teeth,

twenty in the top, fourteen in the bottom. When the jaws closed

the teeth would intermesh, maximising grip on prey. These jaws have

led to the perception that Rhamphorhynchus used

them to snatch up fish

as it skimmed over the top of the water, although it’s not out of

the question that it could also have caught larger insects.

Rhamphorhynchus

has been subject to a lot of study to try and find out more about its

life. One area has focused upon possible sexual dimorphism between

males and females. This is indicated by how long the skull is to the

humerus, with different specimens falling into two distinct groups of

larger and smaller heads. This is not conclusive proof of

dimorphism, but does reinforce the possibility.

Study

of the scleral rings has also indicated a nocturnal lifestyle. It is

difficult to say with certainty if pterosaurs were warm or cold

blooded, but a nocturnal heat source if required could be rocks.

Because rocks have a high thermal capacity, they take a long time to

warm up in the heat of the sun. However, because they take a long

time to warm up they also take a long time to cool down, staying warm

to the touch for several hours after night fall. If cold blooded, a

nocturnal pterosaur could warm up by 'hugging' a rock with its

wings to absorb more heat. If Rhamphorhynchus was

nocturnal, it

would have avoided direct competition with other pterosaurs that were

diurnal. CAT

scans of Rhamphorhynchus skulls have also allowed

for reconstruction of

the the inner ear. This has revealed that unlike some other

pterosaurs, Rhamphorhynchus typically flew with

its head horizontally level

(parallel) to the ground.

A

huge number of species once existed for Rhamphorhynchus,

however many

of these came about from the use of Pterodactylus

as a wastebasket

taxon. It was not until notable differences began to be pointed out

that Rhamphorhynchus became separate. Still a

large number of

differing species existed, or so it was thought until a 1995

study by Chris Bennet revealed that a great many of these specimens

actually represented different life stages of the same species. With

the revelation that these remains were just juveniles, sub-adults and

adults of the same creature, the species list was shortened to just a

handful of names. Of these only R. muensteri is

generally

considered to be true to the genus. The other remaining species which

include R. jessoni, R. intermedius,

are considered subjective

synonyms, while R. tendagurensis thought to be

a nomen dubium.

Although these species are sometimes referred to, their future

validity is uncertain.

Because

it is now accepted that the many various specimens represent the same

species, it has also revealed valuable insights of changing

morphology with age. The jaws of Rhamphorhynchus

juveniles are

short and blunter than they were in adult specimens. Adults also had

shorter and more robust teeth to facilitate larger prey capture that

may have broken weaker teeth. Rhamphorhynchus

also had a vane on the end of its tail and in juveniles was lancet

shaped (like a double edged scalpel). As the individual grew,

the vane would become diamond shaped before becoming a triangle when

full grown.

Further reading

- Pterodactylus (Rhamphorhynchus)

gemmingi aus dem Kalkschiefer von

Solenhofen. - Palaeontographica 1: 1–20. - H. von Meyer - 1846.

- Ein Exemplar von Rhamphorhynchus mit Resten von

Schwimmhaut. -

Sitzungs-Berichte der bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften

mathematisch naturwissenschaftlichen Abteilung 1927: 29–48. - F. Broili

- 1927.

- Odontorhynchus aculeatus novo. gen. novo. sp., Ein neuer

Rhamphorhynchide von Solnhofen. - Neues Jahrbuch f�r Mineralogie,

Geololgie, und Pal�ontologie Beilage-Band 75:543-564. - E. Stolley -

1936.

- Untersuchungen �ber die Gattung Rhamphorhynchus. - Neues Jahrbuch f�r

Mineralogie, Geologie und Palaeontologie, Beilage-Band 77: 455–506. -

Koh - 1937.

- Die Rhamphorhynchoidea (Pterosauria) der Oberjura-Plattenkalke

S�ddeutschlands. - Palaeontographica, A 148: 1-33, 148: 132-186, 149:

1-30. - P. Wellnhofer - 1975.

- A statistical study of Rhamphorhynchus from the

Solnhofen Limestone

of Germany: Year-classes of a single large species. - Journal of

Paleontology 69: 569–580. - S. C. Bennett - 1995.

- Life history of Rhamphorhynchus inferred from

bone histology and the

diversity of pterosaurian growth strategies. - In Soares, Daphne. PLoS

ONE 7 (2): e31392. - E. Prondvai, K. Stein, O. Ősi, M. P. Sander - 2012.

- The Late Jurassic pterosaur Rhamphorhynchus, a

frequent victim of the

ganoid fish Aspidorhynchus?. - PLoS ONE 7 (3):

e31945. - E. Frey,

& H. Tischlinger - 2012.

- Evidence for the presence of Rhamphorhynchus

(Pterosauria:

Rhamphorhynchinae) in the Kimmeridge Clay of the UK. - Proceedings of

the Geologist's Association 126(3):390-401. - M. O'Sullivan &

D. M. Martill - 2015.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|