Parasaurolophus

Name:

Parasaurolophus

(Near Saurolophus/Near lizard crest).

Phonetic: Pah-rah-sore-o-loe-fus.

Named By: William Parks - 1922.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria,

Ornithischia, Hadrosauridae, Lambeosaurinae.

Species: P. walkeri

(type), P. tubicen, P. cyrtocristatus.

Diet: Herbivore.

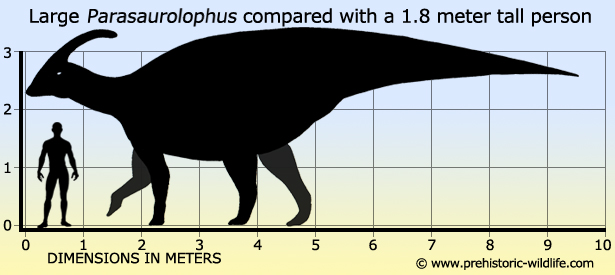

Size: About 9.5 meters long for larger individuals.

Known locations: Canada - Alberta - Dinosaur

Park Formation. USA - New Mexico - Kirtland Formation,

possibly also Fruitland Formation, Utah - Kaiparowits Formation.

Time period: Campanian of the Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: Several skulls and partial

skeletons of varying levels of completeness.

Out

of all the hadrosaurs

(also known as the duck-billed dinosaurs)

Parasaurolophus is one of the most widely

recognised thanks to its

very distinctive skull crest. The name Parasaurolophus

is a bit of a

mouthful, but this is based around the early interpretation that

Parasaurolophus was similar to another genus names Saurolophus

(which

means ‘lizard crest) because Saurolophus also

has a skull crest,

though not as large or as ornate as Parasaurolophus.

However under

modern systematics, Parasaurolophus is classed as

a lambeosaurine

hadrosaurid because of the hollow crest, whereas Saurolophus

is the

type genus of the Saurolophinae (previously Hadrosaurinae) a sister

group of hadrosaurids noted for having solid to no crests at all.

This

means that Parasaurolophus and Saurolophus

are in fact distantly

related, but both are still called hadrosaurids because they both

belong within the Hadrosauridae. Instead Parasaurolophus

is more

closely related to other lambeosaurines such as Hypacrosaurus,

Corythosaurus

and of course the type genus of the group,

Lambeosaurus.

Out of all lambeosaurines however, it is the Asian

genus Charonosaurus

that is thought to be one of the closest relatives

of Parasaurolophus due to the strikingly similar

head crest.

The three main Parasaurolophus species

P. walkeri - This is the type species of Parasaurolophus, which means that the fossils that belong to this species are the ‘benchmark’ that all future fossil discoveries are compared to before they are formally added to the genus. Named by William Parks in 1922, P. walkeri has been established upon a holotype (specific fossils used for identifying future discoveries) of a skull and partial skeleton recovered from what is now the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada. Although not a hundred per cent complete, this specimien has come from an individual that is estimated to have been around nine and a half meters long in life. The skull of P. walkeri features the distinctive long arcing crest that rises up from the skull, but a more simplified network of air passages within. Apart from Canada, there has also been past speculation that P. walkeri remains may also be in Montana, USA, although so far not much has come of this.

P. tubicen - This is the second species of Parasaurolophus, first named in 1931 by Carl Wiman. The species name means ‘trumpeter’. Externally the crest of P. tubicen is very much like that of P. walkeri, but the nasal passages inside are more complex in form. P. tubicen seems to have grown slightly larger than P. walkeri, and is so far known from the remains of at least three individuals. However it is still hard to establish the size of P. tubicen in relation to P. walkeri since the two species together are only represented by fossils for a few individuals, but hopefully future discoveries may allow for a more complete picture. So far P. tubicen is best known from Kirtland Formation and possibly the Fruitland Formation of New Mexico, USA.

P. cyrtocristatus - Named in 1961 by John Ostrom, this is an interesting species of Parasaurolophus and one destined for a lot of future study. The crest of this species is much shorter than the crests of P. walkeri and P. tubicen, and also has a stronger curvature to the point where the end actually reaches around the back of the skull. P. cyrtocristatus also seems to be the smallest known species. Although still widely accepted as being a valid species, study of other hadrosaurids, particularly lambeosaurines has led to the idea that P. cyrtocristatus might actually be juvenile P. tubicen, or alternatively females of P. tubicen. This would actually fit into other patterns set by other genera where specimens interpreted as female seem to have slightly different and reduced crests to those thought to be male. The main counter to this idea however comes from the simple observation that P. cyrtocristatus appears about one million years before P. tubicen. This does not negate the possibility that the two species are the same, but ideally remains of both species need to be found in the same time zones, preferably together. P. cyrtocristatus is currently known from the Kaiparowits Formation of Utah, USA.

What did Parasaurolophus

use its

head crest for?

There

have been many theories about what Parasaurolophus

used its skull crest

for which has led to many erroneous collections of facts about this

dinosaur, but there are three theories in particular that have strong

merit. The first theory is that of visual display, an idea that

explains the difference in crest shape as being a signature feature

between different species. A possible scenario would be an ecosystem

where more than one species or genus of lambeosaurine hadrosaur was

present, but it was difficult to tell the difference between them

because of the similar size and body forms between them. One look at

the head crest however would allow for instant recognition between

species so that they could then focus upon attracting and pairing up

with their own species.

The

second theory that is actually linked to the first is that of auditory

communication. The crest of Parasaurolophus

houses tubes that run up

from the skull to the tip where they curve round and run back down to

the skull. This has given rise to the resonating chamber theory

where calls from the throat of the dinosaur pass through the passages

where they are amplified by the crest so that they are louder and have

a broader frequency. Because lambeosaurine crests are usually quite

different between species and genera, the different shapes would

produce different levels of amplification, in short creating

different sounding calls distinct and unique to a species.

Additionally

going back to the idea that male and female Parasaurolophus

may have

had slightly different shaped crests, the males might have been more

suited for producing louder and longer calls. Just like how male

deer (bucks) roar to signal their strength, the louder and longer

calls of Parasaurolophus (and other

lambeosaurines) could have

belonged to the healthiest and possibly most mature males, both

traits desired by females.

Further

support for the auditory theory comes from study of lambeosaurine

hearing systems (particularly those of Corythosaurus)

which suggest

that hearing was one of the most important and developed senses in

lambeosaurine hadrosaurids. The idea of auditory calling has received

a lot of attention for lambeosaurines, but Parasaurolophus

in

particular has been the most popular study, including computer

reconstructions of the crest with what the sound might have been like

when air was passed through.

The

third contender is that of thermoregulation, particularly with

cooling for the skull and brain. First proposed in 1978 by P.E.

Wheeler, the idea is based around the crest providing a larger

surface area for heat to exchange through. This is a simple principal

where say the only factor involved for losing heat that is changed is

the surface area, so for the sake of argument, a ten square

centimetre area should lose heat ten times faster than a one centimetre

area because of the increased surface area. Other clues for

thermoregulation come from the skeleton where the high neural spines of

the vertebrae significantly increase the height and surface area of the

body for a much smaller proportionate increase in mass.

Unfortunately

the problem with the thermoregulation theory is that it does not

explain the difference in crest forms for other lambeosaurine genera.

If the reason for the crest was more biological, then it would make

more sense if the crests all developed along similar lines with little

variation. It is quite possible however that more than one of the

above theories is correct, after all there is no reason to assume

that a physical feature can only have one purpose. Additionally the

hollow crest may have originally come about as a weight saving feature

to reduce skull weight before adapting to include another purpose.

Older

theories do of course resurrect themselves from time to time, so

let’s take a brief look at these.

Head/Neck support - Actually proposed by William Parks, the palaeontologist who first described Parasaurolophus. The idea is that the crest served as a muscle attachment point for stabilising the head and neck. However there are no signs of muscle attachment points on the neck, and even if the crest was for this function, it would probably hinder this dinosaurs ability to move its neck. Also does not explain the variance in other lambeosaurines since they seem to have managed just fine without any extra support.

Air trap - Proposed by Charles M. Sternberg to keep water out of the lungs, but no feasibly practical way has been produced to demonstrate how which is why it’s considered unlikely. In a variation Ned Colbert suggested that it could be an air reservoir used for when the head is underwater. This is considered unlikely due to the very small storage capacity of the crest, and in such a situation Parasaurolophus would have probably been better off just taking a deep breath.

Snorkel - By Alfred Sherwood Romer, the idea is that Parasaurolophus breathed through the crest so that it did not have to lift its head above the surface of the water. Obvious flaw here is that the crest is not a tube, the end is solid bone. This makes the snorkel idea impossible.

Weapon - By Othenio Abel, but the crest does not have an especially robust construction, and weapons tend to face outwards rather than inwards towards the body. The only feasible way this could work is if a Parasaurolophus dipped its head down and then flicked it up so that the end of the crest struck in an uppercut motion.

Attachment of a Proboscis - By Martin Wilfarth, a proboscis is basically similar to the trunk of an elephant. Why a proboscis would attach to the back of the head is still unknown however since all other vertebrates known to have these always have them on the front.

Branch guard - By Andrew Milner, but this depends upon what Parasaurolophus ate. If Parasaurolophus was hyper specialised in its diet and only ate low growing vegetation that grew under taller and denser vegetation then this might have a benefit. Otherwise it seems strange that a herbivorous dinosaur should have an adaptation for holding away plants it was eating.

Storage of salt glands – Proposed by Halszka Osmolska, and probably the most unique and interesting one here. Salt glands exist to excrete excessive amounts of salts that have been absorbed from the surrounding environment, however they are usually only found upon marine creatures, that is animals that either live in or next to the sea. There is no definitive evidence that Parasaurolophus lived in marine environments, though their known fossil locations of Alberta and New Mexico indicate that they did live fairly close to the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow Cretaceous sea that submerged most of central North America from what is now the Arctic Ocean all the way down to the Gulf Mexico. The idea is considered tentative at best as it does not explain why an unusual crest was needed for this, or indeed the differences between separate species.

Nasal capacity for a greater sense of smell - By John Ostrom and quite a logical proposal given the hollow construction of the crest and its close proximity to the nasal cavity. However unless Parasaurolophus specialised in eating hidden plant parts like those below ground, there is no evidence to suggest that Parasaurolophus did this (i.e. specialised digging hands). Sense of smell might have enabled Parasaurolophus to better detect predators, but predators usually try to approach from downwind of their prey, behaviour that renders the sense of smell next to useless. Also does not explain why saurolophine hadrosaurids that lacked such elaborate had ornamentation seem to have replaced lambeosaurines in North America by the end of the Cretaceous as the dominant group of hadrosaurids.

Parasaurolophus

as a dinosaur of

the late Cretaceous

Once

you get past the head crest, Parasaurolophus was

pretty much just

like every other lambeosaurine hadrosaurid. Most of the time the body

weight would have been supported on all four limbs, though

Parasaurolophus probably could still get about quite

competently on

just the rear legs. This ability to switch between postures meant

that Parasaurolophus like other hadrosaurids had

the flexibility to

adapt to feeding at different heights from low down near the ground to

reaching up into the lower tree canopy. Additionally as a

lambeosaurine, Parasaurolophus had a slightly

narrower mouth than

saurolophine hadrosaurs, suggesting that it could have been a more

selective browser.

There

is fossil evidence to strongly suggest that hadrosaurid dinosaurs like

Parasaurolophus were prey to the top predators of

the Campanian,

principally the tyrannosaurs.

In the north around Canada and

northern portions of the USA the main genera that could have posed a

serious threat to adult Parasaurolophus would have

been Albertosaurus,

Gorgosaurus

and Daspletosaurus.

Albertosaurus

and Gorgosaurus in

particular have a more gracile (lightweight) build which means that

they would have likely been faster than others such as Daspletosaurus.

This would have given these two genera a serious edge in hunting

hadrosaurids which could have been some of the fastest 'large’

herbivores in the ecosystem, especially when you compare them to the

horned ceratopsian

dinosaurs like Chasmosaurus

and armoured ankylosaurs

like Euoplocephalus.

Further

south and the slightly shorter snouted tyrannosaurs such as

Bistahieversor

and Teratophoneus

were the main threats to the more

southern species of Parasaurolophus. Smaller

predators however should

not be discounted as threats, especially against smaller juveniles of

Parasaurolophus. One strong contender is that of

Troodon,

a

dinosaur that although small when compared to a tyrannosaur, could

have combined keen eyesight, slicing teeth and perhaps most

importantly of all, intelligence to bring down smaller individuals.

Further reading

- Parasaurolophus walkeri, a new genus and

species of crested

trachodont dinosaur, William A. Parks - 1922.

- On the genus Stephanosaurus, with a

description of the type

specimen of Lambeosaurus lambei, Parks, Charles

W. Gilmore -

1924.

- Parasaurolophus tubicen n. sp. aus der Kreide in New Mexico

[Parasaurolophus tubicen n. sp. from the

Cretaceous in New

Mexico], Carl Wiman - 1931.

- A new species of hadrosaurian dinosaur from the Cretaceous of New

Mexico, John H. Ostrom - 1961.

- The cranial crests of hadrosaurian dinosaurs, John H. Ostrom

- 1962.

- The evolution of cranial display structures in hadrosaurian

dinosaurs, James A. Hopson - 1975.

- Parasaurolophus (Reptilia: Hadrosauridae)

from Utah, David

B. Weishampelp, James A. Jenson - 1979.

- Aspects of hadrosaurian cranial anatomy, Teresa Maryanska

& Halszka Osmolska - 1979.

- The nasal cavity of lambeosaurine hadrosaurids

(Reptilia:Ornithischia), David B. Weishampel - 1981.

- Acoustic analyses of potential vocalization in lambeosaurine

dinosaurs (Reptilia:Ornithischia), David B. Weishampel -

1981.

- A new skull of Parasaurolophus (long-crested

form) from New

Mexico: external and internal (CT scans) features and their

functional implications, Robert M. Sullivan & Thomas E.

Williamson - 1996.

- A digital acoustic model of the lambeosaurine hadrosaur

Parasaurolophus tubicen, Carl F. Diegert

& Thomas E.

Williamson - 1998.

- A new skull of Parasaurolophus (Dinosauria:

Hadrosauridae)

from the Kirtland Formation of New Mexico and a revision of the

genus, Robert M. Sullivan & Thomas E. Williamson -

1999.

- A juvenile Parasaurolophus braincase from

Dinosaur Provincial

Park, Alberta, with comments on crest ontogeny in the genus,

David C. Evans, Robert R. Reisz & Kevin Dupuis -

2007.

- An unusual hadrosaurid braincase from the Dinosaur Park Formation

and the biostratigraphy of Parasaurolophus

(Ornithischia:

Lambeosaurinae) from southern Alberta, D. C. Evans, R.

Bavington & N. E. Campione - 2009.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|