Ouranosaurus

Name:

Ouranosaurus

(Brave lizard).

Phonetic: Or-an-o-sor-us.

Named By: Philippe Taquet - 1976.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria,

Ornithischia, Ornithopoda, Styracosterna, Hadrosauriformes.

Species: O. nigeriensis (type).

Diet: Herbivore.

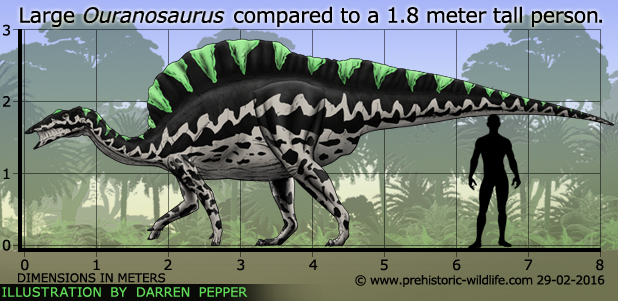

Size: 7 to 8 meters long, 67 centimetre

skull.

Known locations: Africa, Niger - Echkar

Formation. Specimens also known from other locations in Africa.

Time period: Aptian to Cenomanian of the Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: 2 almost complete

individuals.

Ouranosaurus

similarities and differences to Iguanodon

Although

initially classed as an iguanodontid dinosaur, subsequent studies of

Ouranosaurus fossils have revealed it to be a form

of basal

hadrosaur.

Despite this, Ouranosaurus still

bears some features

that are similar to the more famous Iguanodon,

specifically the

forelimb. The hands of the forelimbs still have five digits with the

three central digits being the most robust and arranged to support the

weight of Ouranosaurus when it was in a quadrupedal

posture. The

inner digit is a single thumb spike and the outer is more flexible than

the weight bearing digits.

However

the forelimbs of Ouranosaurus was roughly just over

half the length of

the hind limbs, making them proportionately shorter than those of

Iguanodon. Also not only was the thumb spike

smaller, but the outer

digit was reduced and underdeveloped. In Iguanodon

this fifth digit

is thought to have been prehensile and used for wrap around and pull

down vegetation so that Iguanodon could feed on a

greater abundance of

plant material. Ouranosaurus's fifth digit

however was no way near as

flexible and while it could still potentially be used, it would not

have been as capable as Iguanodons.

At

first impression it may seem strange that a herbivorous dinosaur like

Ouranosaurus would lose an adaptation that should

have helped it to

feed upon plants. What needs to be done however is to look at the

bigger picture, or in this case the whole forelimb, and

environment. Ouranosaurus is thought to have

lived in lowland areas

such as river deltas that were unlikely to have high growing

vegetation, but a large amount of rapidly growing reeds and low

plants. With most if not all of the available food being nearer the

ground, Ouranosaurus would have spent most of its

time on all fours

in a quadrupedal posture, and the shorter forelimbs would have

reduced the distance between its mouth and the food it was eating.

Also the lack of tall growing vegetation would mean that Ouranosaurus

had no need to pull plants down to its mouth which resulted in the

fifth digit becoming less flexible. An additional benefit of this

digit becoming inflexible may have even been to reduce the ground

pressure of the forelimbs as Ouranosaurus walked on

softer water logged

ground, meaning that they did not stick in as much. This all comes

together to suggest that rather than being a generalist browser like

Iguanodon, Ouranosaurus was a

low browsing specialist. Further

support for this theory can also be inferred by the presence of the

sauropod Nigersaurus,

also from North Africa that has a very

specialised skull and mouth for browsing on low vegetation.

Ouranosaurus’s

Beak, Teeth & Skull

Ouranosaurus

was on its way to becoming a duck billed hadrosaurid, and this can be

seen by the broad beak that in life would have been covered with

keratin. This beak would have been very good at pulling up the soft

and leafy plants that grew on the edges of water systems, and the

broad edge would have also allowed for the pulling of multiple small

plants at the same time.

The

beak was not the only food processing mechanism and roughly two fifths

back from the beak the teeth started (the toothless gap between the

end of the teeth and beak is sometimes called the diastema). These

were arranged in rows for small gaps between them where small

replacement teeth were emerging to fill the gaps, thus forming a

constant line of teeth. The presence of teeth suggests that some of

the plant material that Ouranosaurus was eating was

tougher than just

leafy fronds, and may have been the stems and perhaps even roots as

well. It is also possible that Ouranosaurus may

have sometimes fed

upon tougher plants when it was unable to feed from softer vegetation.

There

was probably a limit to just how plants could be until Ouranosaurus

had

real difficulty in eating them. The jaws do not display strong muscle

attachments which suggests that Ouranosaurus had a

very weak bite

force. Herbivores usually do not have high bite forces unless

specially adapted to eat tough fibrous vegetation, and other

well-known dinosaurs such as Stegosaurus

are known to also have low

bite forces. The fact that Ouranosaurus had a low

bite force simply

means that it would have been more predisposed to eat softer

vegetation. The teeth may even have been used to mash the surface of

the plant material slightly so that digestive enzymes could more easily

extract nutrients from it.

The

nostrils of Ouranosaurus were placed high on the

snout, presumably so

that they did not get blocked by mud and dirt as Ouranosaurus

was

feeding. There are also two bony growths on either side of the skull

between the nasal and eye openings which may have been a display

feature or identifying characteristic of the species that allowed

Ouranosaurus to better recognise each other at close

range.

The Neural Spines of Ouranosaurus

The

most spectacular feature of Ouranosaurus is the

presence of tall neural

spines along the dorsal, sacral and caudal vertebrae. Popular

thinking has these spines supporting either a sail or hump that

rose up from the back of Ouranosaurus. The robust

nature of the

spines may lean towards the hump theory or at the very least a thick

and fleshy sail rather than a flap of skin. As always, asking what

kind of structure it was is but the first question, the second one

being what was it there for?

Thermoregulation,

the ability for an animal to have some control over its body

temperature, either cooling or warming, is a popular but

controversial theory. Herbivores tend not to need a high metabolism,

something that would be provided by a higher body temperature,

because they usually rely upon an extensive digestive system.

Another theory is that the growth was primarily a display device to

make individuals stand out to others of their kind, and may have been

brightly coloured, or at least differently to the rest of the body

for this purpose.

Another

option which is more associated with the hump theory is that it

provided food storage in times of abundant food so that Ouranosaurus

could better survive times when food got scarce. In can be hard to

conceive of a river delta that does not have some greenery, but

deltas only exist as long as water keeps flowing into them. Should

the rains fail one season, water levels would drop an even possibly

disappear. Also if Ouranosaurus lived in herds,

the herd may have

quickly depleted the available food in an area meaning that they would

have to keep traveling to find areas of fresh growth. Ouranosaurus

may have even travelled to drier areas further in land to lay eggs

where ground was more stable and less prone to flooding, and needed

to build up food reserves for the journey as well as caring over the

eggs and newly hatched juveniles, as seen in the dinosaur Maiasaura.

While the precise nurturing behaviour of Ouranosaurus

is still not

currently know, it’s not totally inconceivable that it may have

shown similar behaviour. The development of neural spines is also

strongly seen in the African predators Suchomimus

and Spinosaurus,

and this could also point to an adaptation for an ecological factor

such as an especially arid environment or the need to go prolonged

periods without feeding.

Potential Predators

It's

conceivable that Ouranosaurus, particularly

smaller juveniles, may

have come into contact with the spinosaurid

predator Suchomimus.

Although thought to be primarily fish eaters, bones of a juvenile

Iguanodon were found inside the remains of another

smaller spinosaurid

named Baryonyx

from England. Spinosaurids did frequent river deltas

that also seem to have been the main habitat of Ouranosaurus,

making

predation by spinosaurids possible while scavenging of dead

Ouranosaurus probable. The type genus of the

Carcharodontosauridae,

Carcharodontosaurus,

would have also been a

potential threat.

Ouranosaurus

also may have come into contact with giant crocodiles

like

Sarcosuchus.

The larger individuals of this genus approached lengths

of up to twelve meters, making them a very real threat to

Ouranosaurus, particularly not yet fully grown

juveniles and

subadults.

Further reading

- G�ologie et Pal�ontologie du Gisement de Gadoufaoua (Aptien du Niger)

[Geology and Paleontology of the Gadoufaoua Locality (Aptian of

Niger)]. - Cahiers de Pal�ontologie, Centre National de la Recherche

Scientifique, Paris 1-191. - Philippe Taquet - 1976.

- Neural spine elongation in dinosaurs: sailbacks or buffalo-backs? -

Journal of Paleontology 71: 1124-1146 - J. B. Bailey - 1997.

- The Venice specimen of Ouranosaurus nigeriensis (Dinosauria,

Ornithopoda). - PeerJ. 5: e3403. - F. Bertozzo, F. M. Dalla Vechia

& M. Fabbri - 2017.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|