Sarcosuchus

Name: Sarcosuchus

(Flesh crocodile).

Phonetic: Sar-ko-su-kus.

Named By: France de Broin & Phillipe

Taquet 1966.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Diapsida,

Archosauromorpha, Mesoeucrocodylia, Pholidosauridae.

Species: S. imperator (type),

S. hartti.

Type: Carnivore/Piscivore?.

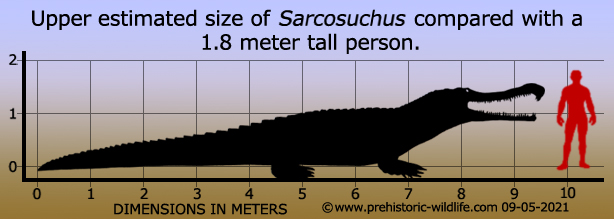

Size: Often credited with being over 11 meters, more

modern estimates roughly suggest a size of about 9 to 9.5 meters long.

Known locations: Algeria - Continental Intercalaire

Formation. Brazil - Ilhas Group. Mali - Continental Intercalaire

Formation. Morocco - Aoufous Formation, Ifezouane Formation. Niger -

Elrhaz Formation, Tagrezou Sandstone Formation. Tunisia - A�n El

Guettar Formation, Continental Intercalaire Formation.

Time period: Hauterivian to Albian of the Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: Mainly specimens are known,

especially teeth and skulls. Parts of post cranial skeleton were

discovered at the end of the twentieth century.

A

very large prehistoric crocodile

Sarcosuchus was initially only known from teeth and

osteoderms. In 1964 the

first skull was discovered and the type species could then be

established. However it was not until the closing years of the

twentieth century that more complete

material including vertebra, ribs and other parts of the post cranial

skeleton. Although still not complete, there is now enough material

to

give a rough estimate on the potential size of Sarcosuchus.

Towards

the end of the twentieth century Sarcosuchus was

thought to have been

around eleven to twelve meters long, an estimate based upon

comparison of the skull to body length proportions of crocodiles alive

today. This method was also used for many other genera of prehistoric

crocodiles, however it also doesn’t seem to have been entirely

reliable in some cases, especially given the variance in skull shapes

and sizes amongst crocodilians. Later twenty-first century studies

(O’Brian et al 2019) using differing comparison methods have a

yielded a slightly smaller estimate of nine to nine and a half meters

for known Sarcosuchus individuals. This still

makes Sarcosuchus

significantly larger than the largest recorded crocodiles alive today

which only rarely attain lengths of six to seven meters.

Sarcosuchus

was not just bigger than today’s crocodiles it was also a lot older.

Most crocodiles have an average lifespan in the wild of around

twenty-five years, with some individuals reaching thirty or more.

Study on the growth rings present on some of the osteoderms show that

Sarcosuchus was around forty years old and yet not

fully

grown when it

died. Whereas todays crocodiles grow large and then stop when they

reach adulthood, Sarcosuchus just kept getting

bigger. It could be

that the only limiting factor to how big it grew was when it could no

longer sustain such a massive body with the available food supply.

As

such a massive predator Sarcosuchus would have had

to of focused its

attention on hunting animals that could provide enough sustenance to

keep its body going, and the two main animal groups available to it

were the dinosaurs and large lobe finned fish. While the idea of

Sarcosuchus shooting out of the water to drag a

hadrosaur off the

shoreline is a tantalising one, you need to look at the teeth and

jaws of Sarcosuchus for clues.

Deinosuchus

had broad jaws and strong teeth, perfect for dealing with large and

powerful prey that would have been struggling as it dragged it into the

water. The jaws of Sarcosuchus however had

proportionately longer and

thinner jaws with relatively small teeth, more suited to a fish

diet. It was not until Sarcosuchus grew bigger

and older that the

jaws began to widen. The tip of the upper jaw also hooked downwards,

another adaption seen in other fish eating crocodiles.

Predatory

dinosaurs of the time and locations include Spinosaurus

and

Suchomimus.

Both dinosaurs have long thin snouts

akin to some

crocodiles and their teeth are many, sharp and pointed. This has

led to most palaeontologists speculating that they were fish hunters,

and if true then there must have been a plentiful supply of fish of

such size and sustenance to keep their numbers and massive bodies

going. A large

crocodile of similar size but less active lifestyle and possibly slower

metabolism would have been even more suited to surviving upon a fish

diet than these dinosaurs.

It

may of course be that Sarcosuchus had different

lifestyles and diets at

different stages of its life. Fish are easy prey for small crocodiles

but as they grew larger they would need more sustenance to survive and

so they may have begun to incorporate dinosaurs into their diets as

well. As seen in crocodiles today, they may have also left the

water to scavenge the kills of the larger dinosaurs as well.

| Name | Time/Location | Size (meters) |

| Deinosuchus (alligator-like crocodile). | Cretaceous/USA. | 10-12 |

| Gryposuchus (gharial-like crocodile). | Miocene/S. America. | 10 |

| Mourasuchus (alligator-like crocodile). | Miocene/Peru. | 12 |

| Purussaurus (caiman-like crocodile). | Miocene/S. America. | 11-13 |

| Rhamphosuchus (gharial-like crocodile). | Miocene/India. | 8-11 |

| Sarcosuchus (crocodile). | Cretaceous/Africa. | 9-9.5 |

| Stomatosuchus (crocodile). | Cretaceous/Egypt. | 10 |

| 3 of todays largest living crocs below | ||

| Alligator mississippiensis (American alligator). | Present/S. E. USA. | 3.4 average - up to almost 6. |

| Crocodylus niloticus (Nile crocodile). | Present/Africa. | Average up to 5, largest up to 6.45. |

| Crocodylus porosus (Salt water crocodile). | Present/India, S. E. Asia, N. Australia. | Average 4-5.5, largest recorded 6-6.6, possibly slightly bigger. |

Further reading

- Notice of some new reptilian remains from the Cretaceous of Brazil.

American Journal of Sciences and Arts 47:442-444. - O. C. Marsh - 1869.

- D�couverte d'un Crocodilien nouveau dans le Cr�tac� inf�rieur du

Sahara [Discovery of a new crocodilian in the Lower Cretaceous of the

Sahara]. - Comptes Rendus de l'Acad�mie des Sciences � Paris, S�rie D

262:2326-2329. - F. de Broin and P. Taquet - 1966.

- The Giant Crocodilian Sarcosuchus in the Early

Cretaceous of Brazil

and Niger. - Palaeontology. 20 (1). - E. Buffetaut & P. Taquet

- 1977.

- The Giant Crocodyliform Sarcosuchus from the

Cretaceous of Africa. -

Science. 294 (5546): 1516–9. - Paul C. Sereno, Hans C. E. Larson,

Christian A. Sidor & Boub� Gado - 2001.

- The 'death roll' of giant fossil crocodyliforms (Crocodylomorpha:

Neosuchia): Allometric and skull strength analysis. - Historical

Biology. 27 (5): 514–524. - R. E. Blanco, W. W. Jones & J. N.

Villamil - 2014.

- New fossils of the giant pholidosaurid genus Sarcosuchus

from the

Early Cretaceous of Tunisia. - Journal of African Earth Sciences. 147:

268–280. - Jihed Dridi - 2018.

- Crocodylian Head Width Allometry and Phylogenetic Prediction of Body

Size in Extinct Crocodyliforms. - Integrative Organismal Biology. 1

(1). - Haley D O’Brien, Leigha M Lynch, Kent A Vliet, John Brueggen,

Gregory M Erickson & Paul M Gignac - 2019.

- Systematic revision of Sarcosuchus hartti

(Crocodyliformes) from the

Rec�ncavo Basin (Early Cretaceous) of Bahia, north-eastern Brazil. -

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society: zlz057. - Rafael G. Souza,

Rodrigo G. Figueiredo, S�rgio A. K. Azevedo, Douglas Riff &

Alexander W. A. Kellner - 2019.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|