Gastornis

Name: Gastornis

(Gaston’s bird).

Phonetic: Gas-tor-niss.

Named By: H�bert - 1855.

Synonyms: Barornis, Diatryma, Gastornis

eduardsii, Gastornis minor, Omorhamphus, Zhongyuanus.

Classification: Chordata, Aves, Anseriformes,

Gastornithidae.

Species: G. parisiensis

(type), G. giganteus, G. geiselensis, G. laurenti,

G.

sarasini, G. russeli, G. xichuanensis.

Diet: Uncertain, but probably herbivorous, refer

to main text for clarification.

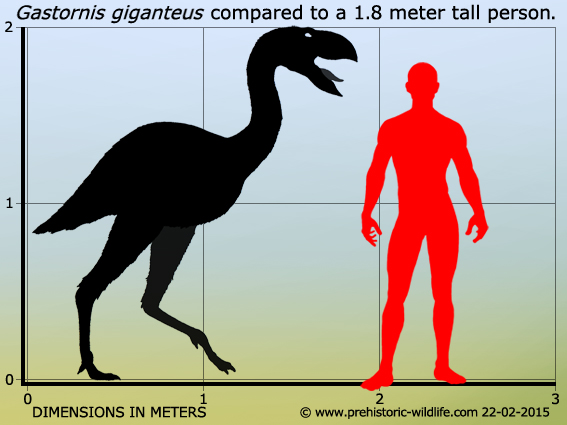

Size: Largest individuals easily up to 2 meters

tall.

Known locations: Belgium. China. England.

France. Germany. USA.

Time period: Paleocene to early Eocene.

Fossil representation: Numerous individuals of

varying levels of completeness, but so many fossils have now been

discovered that the form of Gastornis is now known

without doubt.

History and classification of

Gastornis

Gastornis

was first named as a genus in 1855 by E. H�bert. Gastornis

means ‘Gaston’s bird’, and H�bert chose this name to honour

Gaston Plant�, the man who discovered the first ever (and hence

holotype) fossils of Gastornis in the French

Argile Plastique

Formation that is not far from Paris. This location was in turn the

inspiration of the type species name G. parisiensis,

which simply

means ‘from Paris’.

Further

fossils were found in the 1860s and 1870s, but early

reconstructions of Gastornis were quite some way

out from what we know

today, and this is mainly due to the first reconstructions being

composites of fossils of different animals. This also led to

Gastornis being depicted as more of a crane-like

bird with a very

slender neck and narrow skull. However the actual skull of Gastornis

had not been found save for a few scant fragments, and this

crane-like skull was the perceived 'ideal’ by a man named Lemoine.

At

this time and on the other side of the Atlantic in the United States of

America, the paleontological community was in the midst of the

‘bone wars’, a fierce rivalry between two naturalists named Edward

Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh who were desperately trying to

outdo one another. In 1874 Cope named a new fossil bird that he

called Diatryma. Diatryma was

a huge flightless bird of considerable

size, though much of the skeleton and skull was still missing. In

1894, Marsh named a new genus based upon just a toe bone called

Barornis, though by 1911 it is was declared

to be synonymous

with Diatryma. Very early in the twentieth

century, several

individuals of Diatryma, including almost

complete skulls and

skeletons had been found, not only in the United States, but in

Europe also, and this would be the beginning of questions about the

validity of Diatryma.

A

similarity between Diatryma and Gastornis

was noted as early as 1884

by the American Elliot Coues, and from this point and throughout

most of the twentieth century a fairly quiet but long running debate

about if Diatryma and Gastornis

were one and the same continued to

run. The main sticking point for both supporters and opponents to the

theory was that the reconstruction of Gastornis by

Lemoine did not look

like Diatryma. However, in 1980 the truth

about Lemoine’s

reconstruction being a composite was realised for the first time, and

when known fossils of Gastornis were carefully

compared to those of

Diatryma there was no doubt about the result: Diatryma

was the same

bird as Gastornis. Because the name Gastornis

was

registered some

nineteen years before Cope named Diatryma, and no

special case could

be argued to preserve Diatryma (as what happened

for

Tyrannosaurus),

all Diatryma fossils whether they were from North

America or Europe became known as fossils of Gastornis.

In

1980 a new genus of bird based upon a foot bone from Henan Province

in China was named as Zhongyuanus xichuanensis.

However in 2013

this genus was renamed as a new species of Gastornis,

G.

xichuanensis.

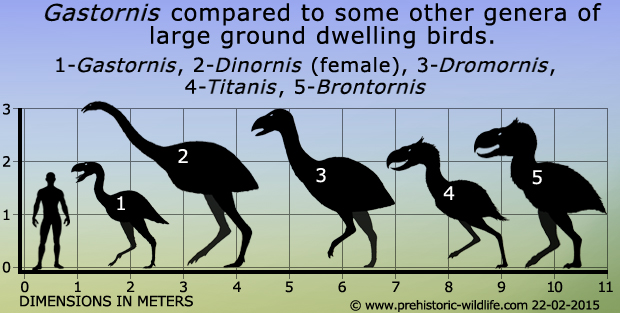

Gastornis

is now the type genus of a group of birds called the Gastornithidae,

but what surprises many people is the fact the Gastornithidae is

usually placed within a larger group called the Anseriformes which

includes modern birds such as ducks, geese and swans. The

gastornithids are distant relatives of the dromornithids, which

include very large flightless birds that used to live in Australia.

There does not seem to be any link direct link between gastornithids

and phorusrhacids

(better known as the South American ’terror

birds’), though there has been some speculation that one

phorusrhacid named Brontornis

may actually be a gastornithid.

Gastornis the

bird

Gastornis

was a very large flightless bird, with the largest species such as

G. giganteus easily reaching heights of two

meters. The legs were

well developed with a stride that could cover a lot of ground allowing

Gastornis to reach quite fast speeds. The wings by

contrast were so

underdeveloped that they were what is known as vestigial, present,

but serving no practical physical purpose. However the vestigial

wings may have still served a display purpose, especially if a

different colour or type of plumage grew from them. As far as

feathers go, Gastornis is usually recreated with

hair-like feathers

that would have been more for insulation and waterproofing during

rainfall. This analysis was based upon early feathers attributed to

Diatryma, but were later found to be plant

fibres. A second feather

that might belong to Gastornis however has now

been identified, and

this is a vaned feather similar to the body feathers that are commonly

seen on flight capable birds. Again, other different feather

types, particularly those for display may have grown upon different

areas, but no clear remains exist at the time of writing.

When

it was still known as Diatryma, Gastornis

was one of the best

represented prehistoric birds in popular science books about

prehistoric animals. Usually this bird would be depicted as a

terrible predator that chased after primitive horses such as

Hyracotherium,

killing them with their beaks. However this

interpretation is now not only seen to be antiquated but just plain

wrong by most researchers.

Gastornis

had a large and robust beak and when the musculature is reconstructed

it is clear that Gastornis would have been capable

of an exceptionally

strong bite. This was once the only evidence that people needed to

suggest that Gastornis was a predator because the

strength of the beak

was far beyond that necessary for an herbivorous diet. However the

beak of Gastornis is also notable for not having a

hooked tip, a

feature that is common in meat eating birds as it greatly helps to hook

into and tear off strips of flesh in the absence of teeth. The feet

of Gastornis are also noted as not having curved

talons which could

hook into and tear into bodies, another feature commonly seen in

meat eating birds, but again absent in Gastornis.

One

of the most conclusive studies concerning the diet of Gastornis

was

published in 2014 (Angst et al) and was focused upon the analysis

of calcium isotopes preserved in the fossils of Gastornis.

These

isotopes clearly indicate that the Gastornis

fossils tested all came

from herbivores (plant eaters) and not carnivores (meat

eaters). Because of this Gastornis is now

perceived to be mostly if

not exclusively herbivorous and using its powerful beak to shear

through tough vegetation.

As

a genus Gastornis is known to have existed for many

millions of years

and with fossils known from Europe, Asia and North America, there

is no doubt that Gastornis was one of the most

successful of the large

flightless birds that once roamed the planet.

Click these names for more information.

Dinornis, Dromornis, Titanis, Brontornis.

Further reading

- Annonce de la d�couverte d'un oiseau fossile de taille

gigantesque, trouv� � la partie inf�rieure de l'argile plastique des

terrains parisiens ["Announcement of the discovery of a fossil bird

of gigantic size, found in the lower Argile Plastique formation of

the Paris region"]. - C. R. Hebd. Academy Sciiences Paris

(in French) 40: 554–557. - 1855.

- Note sur le tibia du Gastornis pariensis

[sic] [Note on the

tibia of Gastornis parisiensis]. - C. R.

Hebd. Academy of

Sciences Paris 40: 579–582. E. H�bert - 1855a.

- Note sur le femur du Gastornis pariensis

[sic] [Note on the

femur of Gastornis parisiensis]. - C. R.

Hebd. Academy of

Sciences Paris 40: 579–582. E. H�bert - 1855b.

- On a gigantic bird from the Eocene of New Mexico. - Proceedings

of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 28 (2):

10–11. - Edward Drinker Cope - 1876.

- Recherches sur les oiseaux fossiles des terrains tertiaires

inf�rieurs des environs de Reims 2. - Matot-Braine, Reims.

pp. 75–170. - V. Lemoine - 1881a.

- Sur le Gastornis Edwardsii et le Remiornis

Heberti de l'�oc�ne

inf�rieur des environs de Reims ["On G. edwardsii and R. heberti

from the Lower Eocene of the Reims area"]. - C. R. Hebd.

Acad. Sci. Paris (in French) 93: 1157–1159. - V.

Lemoine - 1881b.

- The skeleton of Diatryma, a gigantic bird

from the Lower Eocene

of Wyoming. - Buletin of the American Museum of Natural History,

37(11): 307-354. - W. D. Matthew, W. Granger

& W. Stein - 1917.

- The Supposed Plumage of the Eocene Bird Diatryma.

- American

Museum Novitates 62: 1–4. - Theodore Dru Alison Cockerell

- 1923.

- Omorhamphus, a New Flightless Bird from the

Lower Eocene of

Wyoming. - Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society.

LXVII (1): 51–65. - W. J. Sinclair - 1928.

- Fossil Bird Remains from the Eocene of Wyoming. - Condor 35

(3): 115–118. - Alexander Wetmore - 1933.

- New form of the Gastornithidae from the Lower Eocene of the

Xichuan, Honan. - Vertebrata Palasiatica 18: 111-115. -

L. Hou - 1980.

- Biomechanics of the jaw apparatus of the gigantic Eocene bird

Diatryma: Implications for diet and mode of life.

- Paleobiology

17 (2): 95–120. - Lawrence Witmer & Kenneth

Rose - 1991.

- The status of the Late Paleocene birds Gastornis

and Remiornis.

- Los Angeles: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

(Sciences series) 36:97-108. - L. D. Martin - 1992.

- Reappraisal of the Eocene groundbird Diatryma

(Aves:

Anserimorphae). - Papers in avian paleontology honoring Pierce

Brodkorb–Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Science Series

36: 109–125. - Allison Andors - 1992.

- The status of the Late Paleocene birds Gastornis

and Remiornis.

- Papers in Avian Paleontology honoring Pierce Brodkorb. Natural

History Museum of Los Angeles County, Science Series, 36:

97-108. - L. D. Martin - 1992.

- New remains of the giant bird Gastornis from

the Upper Paleocene of

the eastern Paris Basin and the relationships between Gastornis

and

Diatryma. - N. Jb. Geol. Pal�ont. Mh.,

(3): 179-190.

- E. Buffetaut - 1997.

- Footprints of Giant Birds from the Upper Eocene of the Paris

Basin: An Ichnological Enigma. - Ichnos 11 (3–4):

357–362. - Eric Buffetaut - 2004.

- Giant Eocene Bird Footprints From Northwest Washington, USA. -

Palaeontology 55 (6): 1293–1305. - George E. Mustoe,

David S. Tucker & Keith L. Kemplin - 2012.

- The giant bird Gastornis in Asia: A revision

of Zhongyuanus

xichuanensis Hou, 1980, from the Early Eocene of China.

-

Paleontological Journal, 47(11): 1302-1307. - E.

Buffetaut - 2013.

- Reappraisal of the bone inventory of Gastornis

geiselensis

(Fischer, 1978) from the Eocene Geiseltal Fossillagerstatte

(Saxony-Anhalt, Germany). - Neues Jahrbuch f�r Geologie und

Pal�ontologie-Abhandlungen, 269(2): 203-220. - M.

Hullmund - 2013.

- Isotopic and anatomical evidence of an herbivorous diet in the

Early Tertiary giant bird Gastornis. Implications

for the structure

of Paleocene terrestrial ecosystems. - Naturwissenschaften -

D. Angst, C. L�cuyer, R. Amiot, E. Buffetaut, F.

Fourel, F. Martineau, S. Legendre, A. Abourachid

& A. Herrel - 2014.

- Description of a new species of Gastornis (Aves, Gastornithiformes)

from the early Eocene of La Borie, southwestern France. - Geobios. 63:

39–46. - C�cile Mourer-Chauvir� & Estelle Bourdon - 2020.

Random favourites

|

|

|

|