Haast's Eagle / Pouakai

(Harpagornis moorei, Hieraaetus moorei,

possibly Aquila

moorei)

This illustration is available as a printable colouring sheet (pre-orientated in portrait for easier printing). Just click here and right click on the image that opens in a new window and save to your computer.

Name:

Hieraaetus / Harpagornis

(Grappling hook bird).

Phonetic: Har-pag-or-niss.

Named By: Julius von Haast - 1872.

Classification: Chordata, Aves,

Accipitriformes, Accipitridae.

Species: H. moorei (type).

Diet: Carnivore.

Size: Males about 9-12 kg in weight, females

about 10-15 kg in weight. Average wingspan of females about

2.6 meters wide, but some remains suggest a 3 meter wingspan

is possible.

Known locations: New Zealand, South Island -

including the Hillgrove Formation, and the southern portion of North

Island.

Time period: Calabrian of the Pleistocene to the

Holocene. Believed to have gone extinct by around the year 1400AD.

Fossil representation: Remains of multiple

individuals, though often only partial remains. At least three

complete skeletons are known.

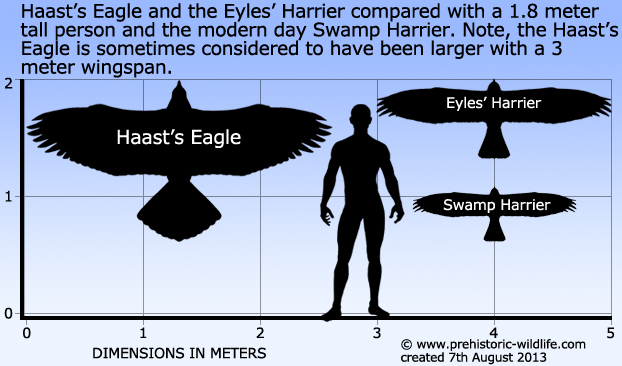

In the simplest terms, the Haast's Eagle is in essence, a giant eagle, and one that focused upon hunting only the largest prey available to prehistoric New Zealand: the large flightless moa birds. Isolated remains and estimates of them suggest that the largest Haast’s Eagles could attain a wingspan of up to three meters long, though a two and a half meter wingspan is more easily established from the majority of known remains. Even with the lower estimate however, the Haast’s Eagle still had a wingspan roughly equivalent to today’s largest eagles such as the Steller Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus), Wedge-tailed Eagle (Aquila audax) and the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos). Where the Haast's Eagle really wins in size though is by weight. Most modern eagles, including the females which are usually larger than the males, never exceed nine kilograms in weight when living in the wild (captive kept eagles are not included in case these are overfed). Estimates of male Haast's eagles however range from nine kilograms all the way up to twelve kilograms, while females could weigh as much as fourteen to even fifteen kilograms. This means that the Haast's eagle is probably one of if not the heaviest eagle that we know about to ever take to the air. Because of the extra weight, it is believed that a Haast's eagle would launch itself into the air by jumping up from the ground while flapping.

The

Haast's Eagle was not a bird that was adapted for long range soaring

over great open distances, the relative shortness of the wingspan is

a clear indication that the Haast's Eagle was adapted for flight

amongst trees and other locations where there was not much room to open

up the wings. By proportion the tail has become enlarged to cover a

larger surface area, something that would help to create lift in the

absence of larger wings. A large tail would also allow for more

stable and more manoeuvrable low speed flight, and would have enabled

Haast's Eagles to have had an exceptional ability for tight turns while

flying amongst trees.

The

Haast's Eagle is also credited as having larger jaws than most modern

eagles, as well as possessing several long talons on the feet. The

talons of the Haast's Eagle are noted as being similar in form to those

of the Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja). These

talons were between

forty-nine to sixty-one and a half millimetres long for the front

toes while the talon of the hallux (the rear toe that was opposable

to the others) was up to one hundred and ten millimetres long. It

were these talons that would have been the primary killing weapons of

an individual eagle.

The

Haast's Eagle was adapted to hunt and kill large prey upon a one on one

basis, but the only suitably large prey in New Zealand for such a

large predator were the moa. Moa were large flightless birds which

are known by several genera, the largest of which of the Dinornis

genus (D. robustus and D.

novaezelandiae) could grow up to

around three and a half meters tall. These birds inhabited the

forests that covered New Zealand during the Pleistocene and Holocene,

and a possible hunting scenario plays out as so;

A

lone Haast's Eagle spots a moa moving though perhaps a less dense

growth of trees and then moves itself into position for a strike.

From an elevated position the Haast's Eagle begins a downward swoop

toward the moa, picking up speed all the while it is making its

approach. The moa may be too busy feeding or dinking to notice the

approach of the eagle which may also be obscured slightly by the

undergrowth. Before the moa can realise the danger the Haast's Eagle

sinks its talons into the spine of the moa, which thanks to a

combination of the sharp edges driven by the momentum of the heavy

eagle travelling at high speed during the point of impact, easily

slice and sever the spinal cord bringing instant paralysis. The

easiest location for a Haast's Eagle to strike would be the pelvis or

the backbone supporting the rib cage since these areas would not be as

likely to move as the head and neck. A strike to the spine in these

areas would also bring paralysis to the legs, causing the moa to

collapse under its own weight. The eagle may have then used a series

of strikes from its talons and beak to more quickly subdue the moa,

or simply wait for the moa to weaken and die before feeding. The

lack of large predators and scavengers on New Zealand meant that a

single moa carcass could sustain an eagle for at least several days.

The only real threat to a Haast's Eagle at this time would be if

another came along and challenged it for territory.

The

precise classification of the Haast’s Eagle seems to be up in the

air at the time of writing. The Harpagornis genus

has been well

established for well over a century, and the popularity of this eagle

has meant that most people know it as and continue to call it

Harpagornis. However, a 2005 DNA study of

Haast’s Eagle remains

by Lerner and Mindell found that it was closely related to the Little

Eagle and the Booted Eagle. Both of these eagles are sometimes

re-classified under the Aquila genus, there has

been quite a

bit of speculation over whether Haast's Eagle should be added to the

Aquila genus as a distinct species, or if it

should remain in its own

genus, Harpagornis. To further confuse matters

now, because the Booted and Little Eagle are still classed as belonging

to the Hieraaetus by some other authors, Haast’s

Eagle is now sometimes

referred to as Hieraaetus moorei.

As

both apex and specialised predators, the future of Haast's Eagles was

certain for as long as there were moa to hunt. However, by

1250-1300AD New Zealand had been settled by the first Māori people,

and this signalled the end for much of the native and specialised

fauna of New Zealand. The first settlers needed to make the land

suitable for long term habitation which meant that vast areas of

forests began to be cleared, destroying the habitat of many animals.

What had a larger impact upon the numbers of Haast's Eagles however

was the active hunting of the moa birds by people. This caused a

significant drop in the numbers of moa which meant that quite suddenly

there was not enough food to support the population of Haast's Eagles

which then began to decline. This continued all the time as the moa

were hunted to extinction, and with the Haast's Eagles unable to

switch to a different food source, they too followed the moa into

extinction.

Haast's

Eagles are usually listed as going extinct at around 1400AD because

this was about the time that the moa birds died out. It’s not

inconceivable that Haast's Eagles might have survived for a little past

this, especially if they had access to a small isolated population of

moa that were still untouched. A claim was made by the explorer

Charles Edward Douglas however that while he was travelling through the

Landsborough River Valley in the 1870s, he shot and ate two raptors

of exceptionally large size. Douglas noted that the birds had

wingspans equivalent to around three meters and were probably the

Pouakai of Maori legend.

However

there is some debate about whether Douglas correctly identified these

birds. The Maori people at the time insisted that the Pouakai was a

bird not seen in living memory, and so far known fossil specimens of

Haast’s Eagles confirm that these birds died out long before Douglas

made his expedition. Instead, modern interpretation of Douglas’s

tale is that he may have actually shot two Eyles'

Harriers, a now

extinct kind of harrier that was also noted for being unusually large,

though not to the extent of the Haast’s Eagle. The reasoning for

this is that although Eyles' Harriers succumbed to the same changing

conditions as what finished Haast’s Eagles, their more generalist

diet means that they may have managed to survive for longer that the

more specialist Haast’s Eagles.

Further reading

- Notes on the weight, flying ability, habitat, and prey of

Haast's Eagle (Harpagornis moorei) - D. H.

Brathwaite -

1992.

- Late-Pleistocene avifaunas from Cape Wanbrow, Otago, South

Island, New Zealand - T. H. Worthy & J. A.

Grant-Mackie - 2003.

- Ancient DNA Provides New Insights into the Evolutionary History of

New Zealand's Extinct Giant Eagle - Michael Bunce, Marta

Szulkin, Heather R. L. Lerner, Ian Barnes, Beth Shapiro,

Alan Cooper & Richard N. Holdaway - 2005.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|