Argentavis

Name:

Argentavis

(Argentina bird).

Phonetic: Ar-jen-tay-vis.

Named By: Campbell & Tonni - 1980.

Classification: Chordata, Aves, Teratornithidae.

Species: A. magnificens

(type).

Diet: Carnivore.

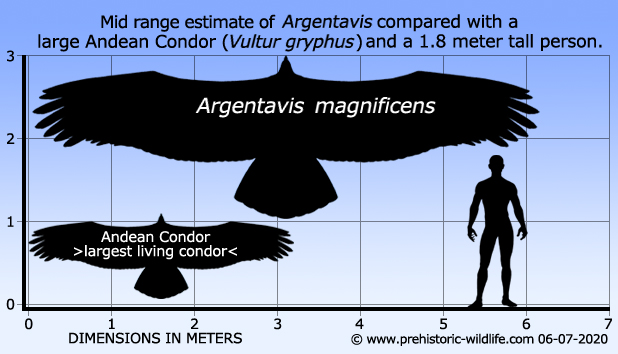

Size: Estimated between 5.5-6.5 meter wingspan,

though some suggest up to 7 meters.

Known locations: Argentina.

Time period: Messinian of the Miocene.

Fossil representation: Several sets of partial

remains.

Take off and Flight

With

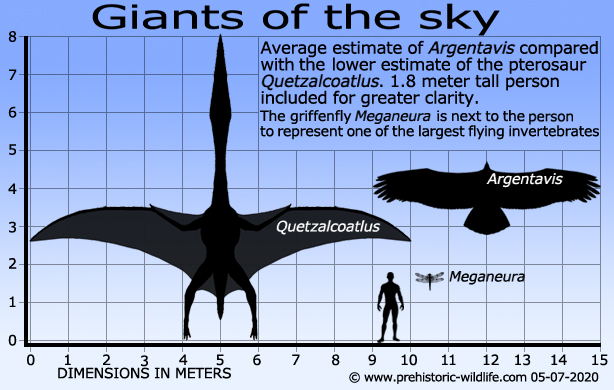

a wingspan estimated at seven meters across, Argentavis

was roughly

twice the size of the largest flying bird today (Wandering

Albatross), and only the long extinct pterosaurs

could have

rivalled and exceeded it for size.The genus Pelagornis

is a possible

contender to be roughly equal in size or slightly wider wingspan to Argentavis,

depending upon accuracy of estimates.

How such a large bird like

Argentavis could fly has been the key area of study

associated

with this bird,

something that has resulted in some interesting conclusions. The

first is that the keel of the breastbone is quite small which suggests

the main flight muscles were reduced when compared to other flying

birds. This means that even though the wings were huge, Argentavis

did not have the stamina to continuously flap them.

It’s

most likely that as a result of these under developed muscles

Argentavis relied upon prevailing wind currents to

keep itself aloft

with flapping only occurring during the take-off and landing phases.

This would see Argentavis using its large wings to

exploit a

combination of thermal up draughts as well as dynamic soaring.

Dynamic soaring is essentially where a flying creature uses the

boundary between two air masses to pick up speed by cartwheeling into

oncoming wind and using the wind speed to accelerate itself forward.

Repeating this process further increases the speed of the bird and

resulting effect of the next manoeuvre resulting in an extremely energy

efficient form of flight, one that is now even used by human glider

pilots to stay airborne longer.

Argentavis

also seems to have relied more upon air currents for taking off as the

immense size of its wings means that it could not flap them when

outstretched without the tips hitting the ground. Instead Argentavis

would have had an easier time just stretching out its wings and facing

into the oncoming wind. From this position Argentavis

could run into

the prevailing wind to get air moving across its wing surfaces and then

use its legs to jump up into the air. This would be the most critical

time for Argentavis as getting airborne is not the

same as staying

airborne (ask any pilot). However if Argentavis

had positioned

itself to run down a slope it could have gotten itself airborne while

increasing the distance between itself and the ground just by flying

horizontally level. Argentavis could then flap

its wings while it

adjusted its course to take better advantage of the air currents.

Argentavis

Behaviour

Feeding

behaviour for Argentavis has been hard to

ascertain, but it is

thought to at least be a carnivore. Argentavis is

not thought to have

been an active predator however due to its body shape and comparatively

weak breast muscles. A much more believable behaviour for Argentavis

would be that of a scavenger, perhaps similar to an Andean Condor

(Vultur gryphus), a bird thought to possibly be

the most similar

living bird to Argentavis but less than half its

size. Scavenging

would also require little in the way of active movement, reducing the

required number of calories to keep its body going.

The

huge size of Argentavis meant that it would have

had little trouble in

driving off smaller mammalian predators like Thylacosmilus

away from

its kills. However it should be remembered that the top predators of

Miocene South America were actually another group of birds, the

ground dwelling phorusrhacids

(better known as ‘terror birds’).

These birds had lost the ability to fly but the largest members of the

group such as Phorusrhacos

and Kelenken

were easily able to take down

large prey. It may have been these predators that provided large

amounts of carrion that supported Argentavis’s

scavenging.

Age and Reproduction

While

no one can say for certain how long Argentavis

lived, its large size

and possibly sedate lifestyle when compared to active predators suggest

that it may have been quite long lived. The large size of Argentavis

meant that it also had no known predators in the air while most of the

ground predators where too small to be a threat. Only the larger

phorusrhacids may have been a problem, but still Argentavis

had the

option of flight, they did not. All of these factors combined has

led most palaeontologists to acknowledge the theory that Argentavis

was

probably a very long lived bird that could have had a lifespan

measureable in decades.

If

the above is true then Argentavis may have relied

upon what is termed a

K-strategy to its life. K-strategy is where an animal species lives

at the extent of its ecosystem limit with very little fluctuation in

total numbers. This prevents the species from exhausting limited food

supplies, and if Argentavis was the scavenger

that most people think

it was, then its food sources would have been dependent upon the

success of other hunters and its own ability to find carrion before

other animals had eaten it. The amount of such food would always be

changing, but a smaller and stable population of scavengers would

have been better able to live of this source than a species that

continually overbred.

To

support the K-strategy Argentavis would have likely

invested a lot of

time and effort into raising a small number of young that would have

stayed with the parent birds for a considerable amount of time. This

would have given the young more time to grow strong while greatly

reducing the level of infant mortality in the species. This would

also help stabilise the population numbers, reducing the risk of

overbreeding as the parents would not breed again until a time until

the young where at a stage of development where they could survive on

their own.

Further reading

- A new genus of teratorn from the Huayquerian of Argentina (Aves:

Teratornithidae) - Contributions in Science, Natural History Museum of

Los Angeles County 330: 59–68. - Kenneth E. Campbel Jr &

Eduardo P. Tonni - 1980.

- Size and locomotion in teratorns - Auk 100 (2): 390–403. - Kenneth E.

Campbel Jr & Eduardo P. Tonni - 1983.

- Ecological and reproductive constraints of body size in the gigantic

Argentavis magnificens (Aves, Theratornithidae) from

the Miocene of

Argentina - Ameghiniana 40 (3): 379–385. - Paul Palmqvist &

Sergio F. Vizca�no - 2003.

- Ancient Argentavis soars again. - Proceedings of the National Academy

of Sciences, 104(30), 12233-12234. - D. E. Alexander - 2007.

- The aerodynamics of Argentavis, the world's

largest flying bird from

the Miocene of Argentina - Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences of the United States of America 104 (30): 12398–12403. - S.

Chatterjee, R. J. Templin & K. E. Campbell - 2007.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|