Hyracotherium

Name:

Hyracotherium

(Hyrax like beast).

Phonetic: Hy-rak-o-fee-ree-um.

Named By: Richard Owen - 1841.

Classification: Chordata, Mammalia,

Perissodactyla, Palaeotheriidae.

Species: H. leporinum

(type).

Diet: Herbivore.

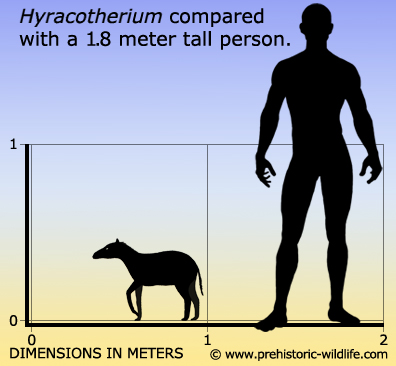

Size: Average 60 to 75 centimetres long.

Known locations: Across the Northern hemisphere,

But best known from Western Europe and North America.

Time period: Ypresian to Lutetian of the Eocene.

Fossil representation: Hundreds of specimens.

For

most of

its history Hyracotherium has been associated with

the genus Eohippus

(dawn horse) that was based upon fossils described by Othniel

Charles Marsh in 1876. This is mostly due to the commonplace

presentation of the name Eohippus towards the

public and subsequent

mention in fiction, the pinnacle of which was the appearance of a

stop motion animated Eohippus in the 1969 film

‘The Valley of

Gwangi’. However some study of Eohippus remains

have

led

palaeontologists to the conclusion that these remains are actually the

same as those of an even earlier named horse called Hyracotherium.

Because Hyracotherium was the first name

established it has, under

international rules governing the naming of animals, priority over

Eohippus which was named thirty-five years later.

Since this time though there has been further evaluation of associated

with these fossils which has led to Eohippus being

preserved as

separate to Hyacotherium.

The

first Hyracotherium

remains were discovered in England and described by Richard Owen, one

of the most important palaeontologists of the day. Owen initially

thought that he might be dealing with a hyrax, a small mammal that

still exists today, but were far more numerous during the Eocene.

However Owen only observed this similarity in the teeth, and much of

the skeleton of this specimen was missing, which resulted in the name

which means ‘Hyrax -like beast’. Marsh’s later described

specimen was virtually complete, and while it was named in the early

period of the ‘bone wars’, Marsh may have only had the

description of the incomplete remains of Hyracotherium

to compare his

discovery against.

Marsh’s

specimen, as well

as other later and more complete discoveries revealed the true nature

of Hyracotherium as one of the most primitive

horses so far known,

which often sees this animal placed in the staring position of the

evolution of horses. Some palaeontologists have even gone one step

further however by suggesting that Hyracotherium is

the form that is

ancestral to the perissodactyl (odd-toed ungulate) mammals that

also include tapirs and rhinos. This extension of the evolution

theory is not supported by all however, and currently most

palaeontologists only refer to Hyracotherium in

terms of horse

evolution rather than wider mammal groups.

Although

Hyracotherium is

seen as a primitive horse, it actually still had toes rather than

hooves, with four on the front feet and three on the rear feet.

Later horses including those we know today support their weight on a

single well developed toe that ends in a hoof. Hyracotherium

was

probably not on open plains runner though, and would have been better

off roaming the undergrowth around forested areas where it could easily

hide its small body from the eyes of the predators of the day.

However as the Eocene progressed the landscapes of the time began to

change from forest to a predominance of open plains that necessitated a

change to a faster running form.

The

teeth of Hyracotherium

are low crowned, a trait that is indicative of a browser of certain

plant parts like leaves and fruits rather than a grazer of grass.

There are forty-four teeth in total with a small gap called a diastema

near the front of the mouth similar to many mammals. This diastema

separates the collecting teeth at the front like the incisors that snip

off plant parts from the processing teeth at the back like the molars

that grind and mash food before it is swallowed. The molars also show

the beginning of the progression towards the molar form of modern

horses. Overall Hyracotherium is generally

thought to have lived and

had a similar ecological niche to that of a small forest dwelling deer.

Hyracotherium

is considered

to have been quite an intelligent animal for its time with a brain that

was proportionately larger in terms of comparison to its body size than

it mammalian contemporaries. It’s thought that this extra brain

size was an advancement towards its senses such as sight, smell and

hearing so that it could detect the presence of other animals,

particularly potential predators. With its lightweight build the

best chance that Hyracotherium had of staying alive

was to use speed

and agility to outrun predators before they got too close to be a

threat.

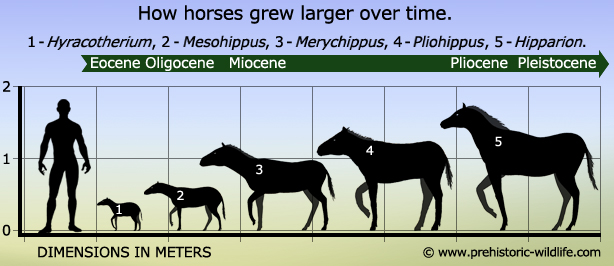

1 - Hyracotherium, 2 - Mesohippus, 3 - Merychippus, 4 - Pliohippus, 5 - Hipparion.

Further reading

- Description of the Fossil Remains of a Mammal (Hyracotherium

leporinum) and of a Bird (Lithornis vulturinus) from the

London Clay. -

Transactions of the Geological Society of London, Series 2, VI:

203-208. - Richard Owen - 1841.

- The beginning of the equoid radiation. - Zoological Journal of the

Linnean Society 112 (1–2): 29–63. - J. J. Hooker - 1994.

- Quo vadis eohippus? The systematics and taxonomy of the early Eocene

equids (Perissodactyla). - Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society

134 (2): 141–256. - D. J. Froehlich - 2002.

- Fossil Horses--Evidence for Evolution. - B. J. MacFadden - 2005.

Random favourites

|

|

|

|