Coelodonta

(Woolly Rhino)

Name:

Coelodonta

(hollow tooth)

Phonetic: See-low-don-tah.

Named By: Bronn - 1831.

Synonyms: Rhinoceros tichorhinus,

Coelodonta boiei.

Classification: Chordata, Mammalia,

Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae.

Species: C. antiquitatis

(type),

C. nihowanensis, C. thibetana, C. tologoijensis.

Diet: Herbivore.

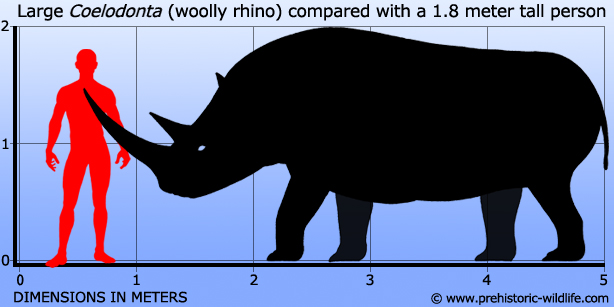

Size: 2 meters tall at the shoulder, between

3 to 3.8 meters long. Some specimens may have been slightly

larger.

Known locations: Across Eurasia (Europe,

Russia, Asia).

Time period: Piacenzian of the Pliocene to early

Holocene.

Fossil representation: Multiple specimens,

including animals that have been completely preserved so that the full

body and not just the bones is preserved.

Coelodonta

is one of the most commonly represented ‘ice age’ mammals, yet

surprisingly it often only gets a name mention. Popularly known as

the woolly rhino, Coelodonta resembled the large

rhinos that we know

today from Africa, but with a complete covering of fur over its

body. This was the main survival adaptation of Coelodonta

which

inhabited most of Eurasia for over two and a half million years.

Coelodonta

lived at a time that saw a series of glaciations across the Northern

hemisphere that saw sheets of ice sweeping over much of the land, to

receding back before covering the land again. This toing and froing

of the ice sheets, combined with the colder climate that caused much

of the lower soil depths to be permanently frozen, created vast

expanses of frozen plains that were covered in grasses interspersed

with low growing vegetation, and it is this ecosystem that

Coelodonta seems to have been most adapted to. As

with many similar

herbivores, Coelodonta had sharp incising teeth

at the front of the

mouth and mashing molar teeth at the back. Between these two sets of

teeth was a gap called the diastema, something else that is common

amongst herbivorous mammals.

It’s

uncertain exactly what kind of herbivore Coelodonta

was. Some people

think that Coelodonta was a grazer that cropped the

grass plains like a

cow, while others believe that it was a browser than fed from low

growing plants. Either one is plausible; although most lean towards

the grazing idea as grasses would have been much more abundant than

more complex low growing plants. Coelodonta is

thought to have used a

fermentation method of processing the cellulose rich grasses in order

to get the full nutritional benefit from the nutritionally poor

vegetation of the ecosystem. This is actually a very clever method of

digestion to adopt since as the grass is broken down by fermentation

inside the gut of Coelodonta, it generates a

small amount of heat

that would have the added effect of warming the body from the inside.

This

method of digestion seems to have been very efficient for Coelodonta

as

specimens where the main body is still preserved show that Coelodonta

had a hump that rose up from its back above the shoulder blades. This

hump was supported from within by the forwards dorsal vertebrae that

had elongated neural spines growing from them, much larger the neural

spines of the other vertebrae. This hump would have served as fat

storage so that Coelodonta could build up fat

reserves in the milder

spring and summer so that it could better survive the colder winter

when the plants had begun to die back, and possibly even had a deep

covering of snow and ice.

Efficient

processing of plants that have a low nutritional value is important for

an animal like Coelodonta, but just as important

for survival is

efficient energy use and conservation. As a mammal, Coelodonta

was

certainly warm blooded, which means that the body works to try and

maintain a stable temperature different from it environment (in this

case much higher). Usually this is done by a process of involuntary

muscle actions to generate heat such as the rapid and repeated

constriction of muscle fibres, better known as ‘shivering’. In

the short term shivering is not a problem, but prolonged shivering

results in more calories being burned (used up), and the more

that are burned the more likely that an animal will use up all it has.

With no more calories to use, and not enough coming from the plants

to maintain the level of use, an animal will stop shivering and

quickly succumb to the cold, quite possibly dying from exposure.

As

briefly mentioned above, Coelodonta had a

covering of fur over its

body, something which led to the name ‘woolly rhino’. This was

the main line of defence against the cold, and would have trapped

layers of air near to the skin. With these layers protected from

mixing with the outer air they would be warmed by the body, and

because this layer of inner air did not require any energy to

maintain, it would have been like a blanket that slowed down the rate

of heat loss from the body to the outside environment. A similar

effect to this is simply wearing clothes as these layers of fabric trap

pockets of air against your body to keep you warm. The effect is

especially pronounced for thicker garments such as jumpers which offer

a greater level of insulation. In addition to the fur, the body

proportions of Coelodonta also helped to prevent

heat loss. For

example, the short legs of Coelodonta are a

further adaption to the

cold environment as they would reduce the surface area exposed to the

cold climate, reducing the area for heat loss to take place.

No

description of a rhino would be complete without mentioning the horn

and this goes double for Coelodonta as it had two

pronounced horns

rising from its snout. The front horn at up to two meters long was

the longer of the two, with the second horn rising from the middle of

the snout being just over half to two thirds as big. The classical

explanation for these horns is that they were what are termed

sexually selected characteristics. This is based upon the knowledge

that the horn would have been growing throughout the animals life, no

more than a stump in a juvenile to fully developed in mature

individuals. An older animal would have a more developed horn than

younger individuals signalling to members of the opposite sex that it

had the genetic makeup and success to make it to later life, and was

more deserving of passing its genes down to the next generation than

lesser individuals that had less developed horns. Such reasoning

would explain the progression to larger horn sizes.

However

there is a second theory regarding the front horn that is both an

alternative and possible addition to the above theory. The front horn

is strongly curved so that it extends out beyond the end of the snout.

This horn is also laterally compressed so that when viewed from the

front the horn looks more like a blade rather than a cone like in other

genera. This leads to the popular interpretation the front horn was

not just a display device but an actual tool that Coelodonta

used to

scrape snow off the ground as it moved its head from side to side.

This would expose buried grasses that allowed Coelodonta

to feed

further without using energy to walk to an area that was uncovered,

and would have been of particular use when Coelodonta

was in areas

that had frequent snowfall, but not a permanent covering.

The

earliest remains of Coelodonta are from India and

have been dated back

to the end of the Pliocene period. The majority of other Coelodonta

remains so far known are from Europe and Russia and these date back to

the Calabrian of the Pleistocene, which suggests that Coelodonta

first emerged in central Asia and then expanded its range. This

expansion could have been synchronised to the availability of

tundra-like environments that were constantly changed from the varying

expansion and receding of the ice sheets that once covered the northern

hemisphere.

One

of the best examples of Coelodonta comes from a

Tar Pit in Poland

(near Starunia) that had its body frozen and preserved. Before

this time the only visual representation of the living Coelodonta

was

in the form of cave art that had been made by ancient human beings.

Further reading

-Nuevas aportaciones al conocimiento de Coelodonta

antiquitatis

(Blumenbach, 1799) de Brown Bank, Mar del Norte [New contributions to

the knowledge of Coelodonta antiquitatis

(Blumenbach, 1799) Brown Bank,

North Sea] - Bulletin Centre d'Est. Natura B-N. VII 13): 309-329 Sta.

Coloma de Gramenet - David Garcia Fern�ndez & Juan Vicente i

Castells - 2008.

- Out of Tibet: Pliocene Woolly Rhino Suggests High-Plateau Origin of

Ice Age Megaherbivores. - Science 333 (6047): 1285–1288 - T. Deng, X.

Wang, M. Fortelius, Q. Li, Y. Wang, Z. J. Tseng, G. T. Takeuchi, J. E.

Saylor, L. K. S�il� & G. Xie - 2011.

Random favourites

|

|

|

|