Top 10

Tyrannosaurs

Featuring tyannosaurids of the Tyrannosauridae as well as the more primitive tyrannosauroids of the Tyrannosauroidea

10 - Guanlong

As far as tyrannosaurs go, Guanlong is considered to be a proceratosaurid tyrannosauroid. In more simple terms this means that Guanlong is a basal tyrannosaur that appeared at the same time as other primitive tyrannosaurs, yet may not actually be a direct ancestor of the later large tyrannosaurs that were roaming around Asia and North America in the late Cretaceous. Never the less, Guanlong is still regarded as a basal tyrannosaur, and is a very good example of how these fearsome predators actually started out quite small.

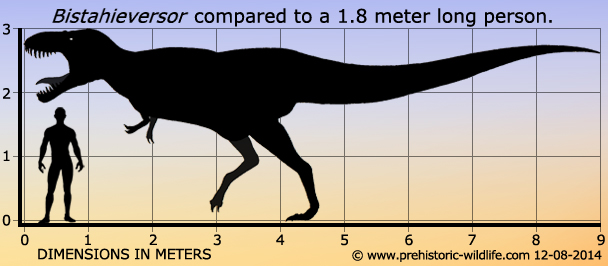

9 - Bistahieversor

Named

in 2010 Bistahieversor was among several

tyrannosaur genera named

in the early years of the twenty-first century. The discovery of

Bistahieversor may have opened up a whole new

sub-group of

tyrannosaurs, those that lived in the southern portion of the

landmass known as Laramidia. Back in the Cretaceous, the North

American continent was divided into two by the Western Interior Seaway

which submerged central North America all the way from Canada to

Mexico, with the western land mass known as Laramidia, and the

eastern Landmass known as Appalachia.

Bistahieversor

was discovered in New Mexico, meaning that it lived in southern

Laramidia, a significant discovery in itself since most tyrannosaur

fossils at that time had been discovered much further north,

particularly around what is now the northern United States and

southern Canada. An additional discovery about Bistahieversor

though

was that the snout, the portion of the skull in front of the eyes,

was proportionately shorter than the known skull proportions of more

northern tyrannosaurs. Then only one year later another tyrannosaur

genus named Teratophoneus

was discovered in Utah and it too had a snout

that was proportionately shorter than these living further north.

These two genera were subsequently the start of a theory that the

tyrannosaurs of southern Laramidia might have been isolated from their

North American cousins by rising mountain ranges and began developing

along different lines.

8 - Lythronax

Another tyrannosaur named in the early twenty-first century, Lythronax has been credited as one of the earliest known appearances of an actual tyrannosaurid, with other tyrannosaurs appearing earlier in the Cretaceous being designated as more primitive tyrannosauroids. The Lythronax holotype was recovered from Utah, which means that Lythronax lived in southern Laramidia. Like the aforementioned Bistahieversor and Teratophoneus, Lythronax too had a comparatively short but deep snout.

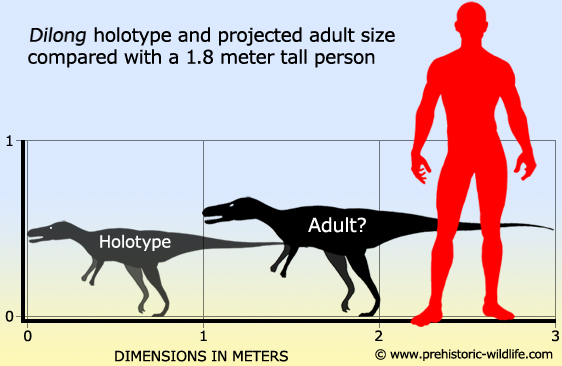

7 - Dilong

Hailing from China, Dilong was a very small tyrannosaur that lived during the early Cretaceous. What otherwise might have been an unassuming little dinosaur still managed to shake the foundations of tyrannosaur and theropod dinosaur study, Dilong had feathers! The feathers that were on Dilong were small and really more like hairs, and were almost certainly for the purpose of heat insulation (though they may have also been coloured for additional display). The discovery of Dilong was the catalyst to the question, were other tyrannosaurs feathered? We still don’t know how to answer that question properly, there is evidence to suggest that they were and were not, and may have varied depending upon age with smaller juveniles being feathered for insulation but adults losing them because they were not necessary. But as we’ll see, it might not be that clear cut.

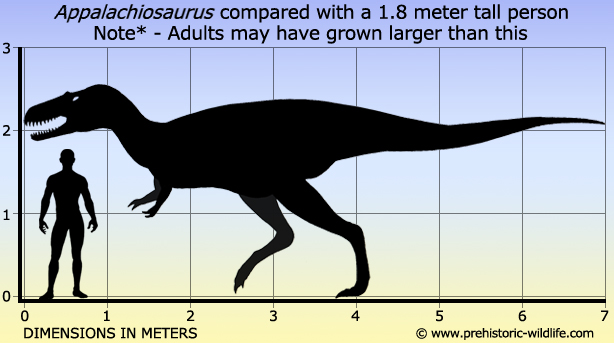

6 - Appalachiosaurus

Whereas most tyrannosaurs in North America are known from fossils in what was once the western landmass of Laramidia, the holotype fossils of Appalachiosaurus were actually discovered in the eastern landmass of Appalachia, leading to the name Appalachiosaurus which translates to English as ‘Appalachian lizard’. The discovery of Appalachiosaurus has revealed that tyrannosaurs were probably roaming across both sides of North America during the Cretaceous. The holotype specimen of Appalachiosaurus was found to have a tooth from the giant crocodile Deinosuchus stuck in one its tail vertebrae.

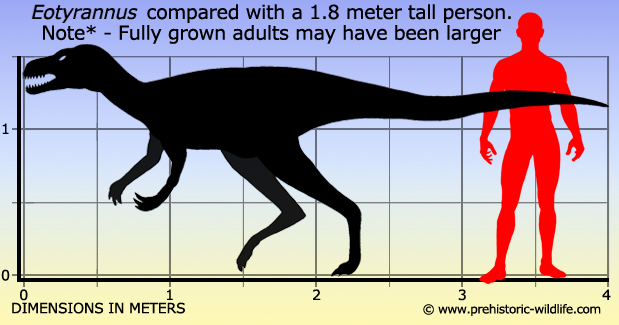

5 - Eotyrannus

For the best part of a century the tyrannosaurs were popularly regarded as large predatory dinosaurs that hunted in what we now call eastern Asia and North America. What makes Eotyrannus different is that it didn’t live in Asia or North America, the holotype fossils of this genus were discovered in England! Not only does this make Eotyrannus the first tyrannosaur genus to be discovered in the British Isles, but the first tyrannosaur to be discovered on the European continent. The holotype fossils of Eotyrannus indicate an individual that was about four meters long, but this individual was also a juvenile, and fully grown adults would have certainly been larger, though exactly how much larger is difficult to say without a second, ideally adult specimen. Being larger than four meters would be just as well however as the carcharodontosaur Neovenator and the spinosaur Baryonyx are both known from the same fossil formation as Eotyrannus, and both of these are known to have been much larger than the holotype individual.

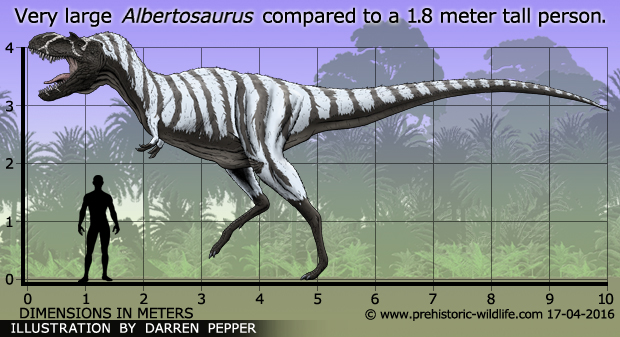

4 - Albertosaurus

Albertosaurus

is one of the more famous tyrannosaur genera from North America, and

one of the last known to live at the end of the Cretaceous before the

dinosaurs died out. With the largest individuals reaching sizes of

ten meters long, Albertosaurus had a relatively

gracile (light)

build for a tyrannosaur and was similar to the genus Gorgosaurus

(which some palaeontologists consider to be the same genus as

Albertosaurus, though others insist that they were

different).

The

main controversy concerning Albertosaurus is the

theory about if they

were pack hunters, a theory stemming from the Dry Island bonebed.

Situated near the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada, the bonebed

was first discovered in 1910 by the famous American palaeontologist

Barnum Brown, yet was surprisingly forgotten about until it was

re-discovered in 1997 by an expedition from the Royal Tyrrell

Museum of Palaeontology. This bone bed has the remains of at least

twelve, but possibly as many as twenty-six Albertosaurus

individuals. In addition to this great number, the individuals

range from very small juveniles, to very large ten meter long adults.

There

are many ways that such a bonebed could be read but the accumulation of

such a large concentration of all the same dinosaur and not anything

else does suggest that this is bonebed is not the result of a random

placement. If it represents the remains of a family pack is

controversial and certainly not certain, but other large theropod

groupings have since been found though certainly not yet in such

numbers as the Albertosaurus bone bed.

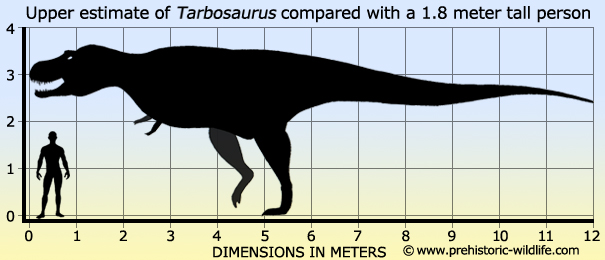

3 - Tarbosaurus

With

the exception of Alectrosaurus,

the tyrannosaurs were regarded as

primarily North American dinosaurs for the first half of the 20th

century, then in 1955 things changed with the description of

Tarbosaurus. The problem with Alectrosaurus

was that it was only

named from very partial fossil material that had been perceived to be

similar to Gorgosaurus from North America, but

further details were

impossible. The Tarbosaurus holotype however was

much more complete,

so much so that when it was first named it was described as a species

of Tyrannosaurus, Tyrannosaurus bataar.

It

was not long before the specimen was renamed Tarbosaurus,

but the

debate about whether Tarbosaurus should be a

distinct genus or a

species of Tyrannosaurus has been ongoing ever

since as the differences

between them are only slight. Most modern thinking however seems to

support keeping Tarbosaurus as a distinct genus,

and studies

associated with the aforementioned Lythronax above

suggest that the

Asian tyrannosaurs are of a group that are distinct (but still

related) to the North American tyrannosaurs.

Tarbosaurus

is so far known mostly from Mongolia, with some remains from China.

The genus Alioramus

which is also known from Mongolia, was once

considered to be a juvenile Tarbosaurus, but new

specimens of this

dinosaur prove that it is a distinct genus from Tarbosaurus,

though

one that was closely related to it.

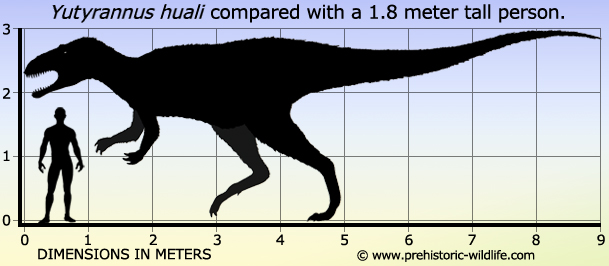

2 - Yutyrannus

When

Dilong was found it led to speculation that smaller

tyrannosaurs and

juveniles of larger ones probably had feathers. Then in 2012

three individuals of a new tyrannosaur genus were found in Aptian aged

rock in China. All three of these tyrannosaurs had feathers, and

the largest individual was up to nine meters long! The idea that only

small tyrannosaurs had feathers is now out of the proverbial window,

but Yutyrannus may be an exception not the rule.

Analysis

of the fossil site suggests that Yutyrannus

came from a colder

climate and thus necessitated the need for feather insulation when

fully grown. By comparison the limited known skin impressions of

tyrannosaurs from North American indicate that at the time of death

these individuals had bare skin, and not an extensive covering of

feathers like Yutyrannus. It could be because the

North American

tyrannosaurs were living in a warmer climate, or perhaps after many

more millions of years of evolution they lost their feathers, or

perhaps even developed medical conditions that caused feather loss

which then partly resulted in their deaths. What is known for certain

is that when Yutyrannus was described it gained the

title of largest

known feathered dinosaur, comfortably beating the previous record

holder, a therizinosaur

named Beipiaosaurus.

The

description of feathers upon such a large dinosaur can easily

overshadow the overall significance of a discovery. When Yutyrannus

was found, it was three individuals, all of different ages that

were found together. Like with Albertosaurus,

this raises the

question, did Yutyrannus hunt in packs? Perhaps

as a small family

unit?

1 - Tyrannosaurus

What

else could it be? Tyrannosaurus has been by far

the most popular

dinosaur ever since it was introduced to public in the early 20th

century, and since this time whenever a film, book or video game

needs a dinosaur for a primary antagonist, nine times out of ten it

will be a Tyrannosaurus.

Partly

because of the popularity, Tyrannosaurus has had

to put up with a lot

bad publicity with a lot of people accusing it of only being an

‘obligate scavenger’, despite the fact that many of the arguments

that claim to 'prove’ this can easily be dismissed as nonsense.

This is not to say that Tyrannosaurus never

scavenged carcasses, it

would be very strange if Tyrannosaurus didn’t

because scavenging is

actually normal behaviour for all meat eating animals. But taking

advantage of the occasional 'free meal’ is very different from only

scavenging and never hunting.

For

the best part of a century Tyrannosaurus was

regarded as the largest

known theropod dinosaur, and it was not until later in the twentieth

century that Tyrannosaurus lost this title. Tyrannosaurus

is still

comparable to the largest theropods, and as of 2014 is still the

largest known tyrannosaur. Tyrannosaurus is also

regarded as having

potentially the most powerful bite of not just any dinosaur, but also

any known land animal of all time. This is thanks largely to the size

and width of the skull which allows for larger jaw closing muscles.

In addition to that, the skull width and eye placement would have

allowed for visual ability far surpassing that of any human, and even

birds of prey like eagles which are regarded as having some of the best

eyesight in the known animal kingdom.

Random favourites

|

|

|

|