Top Ten Predatory Dinosaurs

A look at ten of some of the most famous, largest and specialised predatory dinosaurs that are known to science. If you would like to know much more detailed information about these dinosaurs, just click on their names to go to their main pages.

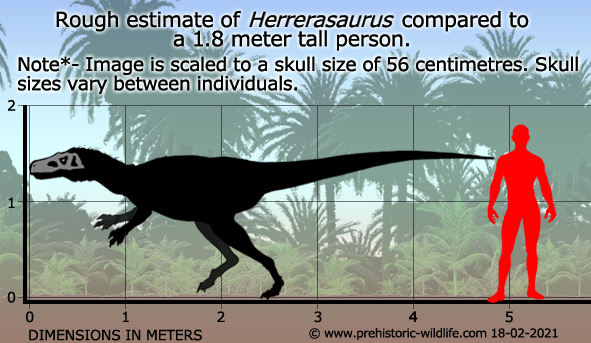

10 - Herrerasaurus

The oldest dinosaur on this list, Herrerasaurus dates all the way back to the Triassic when dinosaurs were living in a world dominated by large rauisuchians. But Herrerasaurus was no slouch, and was perfectly capable of hunting other primitive dinosaurs that were mostly much smaller than Herrerasaurus. However despite the fact that Herrerasaurus superficially looks like the later theropods in form, it displays a number of features that are individually common across different dinosaur groups. For this reason Herrerasaurus is considered by some to represent one of the oldest dinosaur forms that predates the split into the two main saurischian (lizard hipped) and ornithischian (bird hipped) groups. Herrerasaurus also has a sliding jaw joint, very unusual for a dinosaur, but something that may have helped it to grip prey with its mouth.

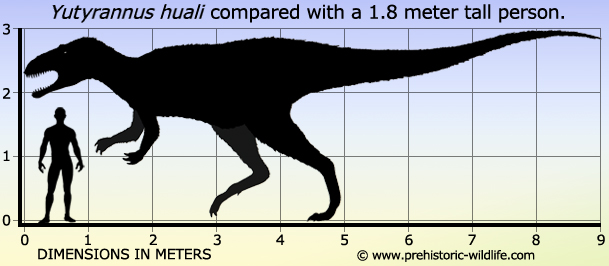

9 - Yutyrannus

When named in 2012 Yutyrannus made people sit up and take notice. Not only was this a nine meter long tyrannosaur, it had a body that was covered in hair-like feathers. This made Yutyannus the largest confirmed feathered dinosaur, easily beating the then previous record holder, the therizinosaur Beipiaosaurus. Yutyrannus re-ignited the debate over whether all dinosaurs were feathered, though the actuality of the situation is probably that some were and some were not. Study of the fossil site of the Yutyrannus holotype indicates that it would have been at a high elevation back in the early Cretaceous with a cool average air temperature. Skin impressions of other tyrannosaurs speculated to live in warmer climates however have been preserved without feather impressions, showing that the question over if dinosaurs had feathers should be dealt with on a case by case basis rather than just assumed to apply to the whole.

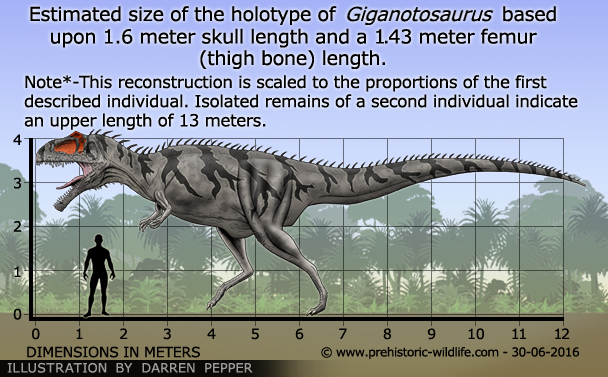

8 - Giganotosaurus

This

is the dinosaur that in 1995 made headlines around the world for

being bigger than Tyrannosaurus. Unfortunately

this estimate is based

upon an estimated range of twelve to thirteen meters long, and if the

lower end of the estimate proves more correct then it is actually not

bigger at all, just similar in size. Also at the higher end it

would be only around twenty centimetres longer that the longest

recorded Tyrannosaurus specimen. Despite this

however, partial

remains of a second individual, bigger in scale to the type specimen

suggest that Giganotosaurus may have actually still

grown quite larger

than Tyrannosaurus, although by how much still

remains uncertain in

the absence of more fossils.

Arguments

about which dinosaur was bigger often carry away from the actual facts

of Giganotosaurus which was a member of the

carcharodontosaurid group

of theropod dinosaurs. Others of this group such as

Carcharodontosaurus

also reached large sizes that were comparable to

Tyrannosaurus, but these dinosaurs actually had

very different teeth

that worked to slice flesh rather than crush bones and armour. This

means that Giganotosaurus may have had to deliver a

series of bites to

the body of its prey so that it succombed to blood loss and collapsed.

It’s possible that Giganotosaurus may have also

left most of the

bones untouched and just ate the soft parts to avoid unnessecary damage

to its teeth.

7 - Acrocanthosaurus

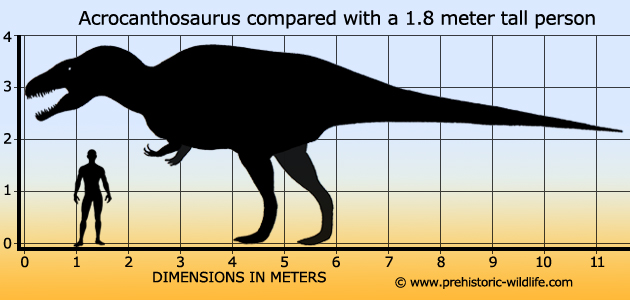

This

theropod lived during the early/mid Cretaceous, yet it grew to a size

that was comparable to the later Tyrannosaurus.

This large size

suggests that Acrocanthosaurus was the apex

predator of North

America, after Allosaurus and before the

tyrannosaurs, and with

most of the other predatory dinosaurs such as Deinonychus

being much

smaller, Acrocanthosaurus would have dominated

the landscape.

Large

size is not the only claim to fame for Acrocanthosaurus

as it also

featured vertebrae that had elongated neural spines. These projected

upwards to support a hump that ran down the back (it has also been

suggested that they supported a skin sail as well as supporting a row

of spines, but these theories are not as widely accepted as they used

to be). This hump probably served as fat storage for lean times,

but it may have also been a display feature that showed others of its

kind how successful a predator an individual was, to a sign of

maturity to even just making Acrocanthosaurus look

like it was even

bigger.

6 - Spinosaurus

Aside from possibly being the largest theropod on the list, Spinosaurus is easily the most specialised. One specialisation, the reason for the name and the feature that most people are familiar with, is the enlarged neural spines of the dorsal vertebrae that supported either a skin sail or a hump on back. The purpose for this growth has been explained for everything from thermoregulation, display, to fat storage but it still remains a mystery to be certain. The features that reveal more about the actual hunting behaviour of Spinosaurus are the long crocodile-like jaws that were filled with narrow conical teeth. These jaws and teeth are seen in other piscivorous (fish eating) animals such as crocodiles and even pterosaurs. Additionally the snout of Spinosaurus is covered in pores that seem to have been the housing for pressure sensors that allowed Spinosaurus to detect passing fish in the water. These features combined now give what is considered a much more accurate depiction of Spinosaurus as a large fish hunter rather than a generalist predator of other dinosaurs.

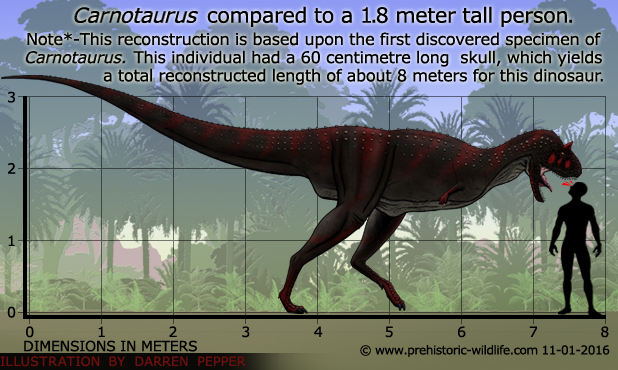

5 - Carnotaurus

Dinosaurs

that look different are on the road to overnight fame, and

Carnotaurus achieved this by having two stubby horns

growing from the

skull above its eyes. Carnotaurus was a large

abelisaur theropod, a

group noted for having short but tall skulls, and arms that are even

more vestigial than those of the tyrannosaurs. One popular idea about

predators like Carnotaurus is that they used their

narrow skulls like

hatchets, relying upon the momentum of their head movements to drive

their teeth through their prey rather than the bite muscles. The

skulls of abelisaurs were also well suited to the job of holding onto

prey, and if Carnotaurus managed to clamp its

jaws around the neck of

a prey animal, it may have been able to choke it with its jaws.

The

abelisaurs were one of the last two great groups of large theropod

dinosaurs, and while the tyrannosaurs dominated in the northern

continents, the abelisaurs held domain over the south, with earlier

theropod groups only existing in small fragmented populations. During

the late Cretaceous of South America, Carnotaurus

was one of the

greatest of the abelisaurs.

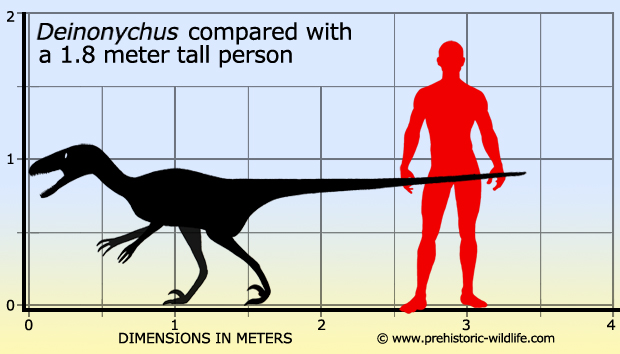

4 - Deinonychus

When people think ‘raptor’ they usually think about how Velociraptor was depicted in the ‘Jurassic Park’ movies, but what many people still do not realise is that these ‘raptors’ were actually based upon Deinonychus. This dinosaur would have been the terror of North America towards the end of the early Cretaceous, not just because of the long sickle shaped claws on its feet, but because Deinonychus is one of the main inspirations about dinosaurs hunting in packs. Although not all palaeontologists are convinced about this the idea has remained and continues to be studied, with more evidence about the possibility of pack hunting pointing towards Deinonychus than most other dinosaurs.

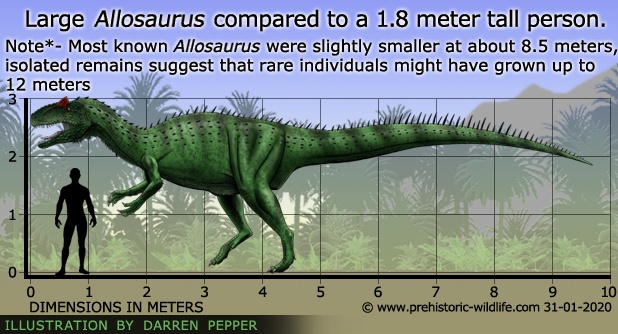

3 - Allosaurus

Not

only is Allosaurus the best represented large

theropod dinosaur in the

fossil record, it seems to have been ‘the’ predator design of the

late Jurassic. Aside from being numerous, many of the other large

Jurassic theropods are so much like Allosaurus that

palaeontologists

still today question if they really represent new dinosaur genera or

are merely different species of Allosaurus.

The

large number of remains of Allosaurus have allowed

for a lot of study

of this particular dinosaur. Injuries to the arms where tendons have

been ripped from the bones suggest that Allosaurus

was very physical in

its attacks upon other dinosaurs and it would have done so without much

thought or fear of injury to itself. This is further evidenced by

fossils that prove Allosaurus got into fights with

armoured dinosaurs

like Stegosaurus.

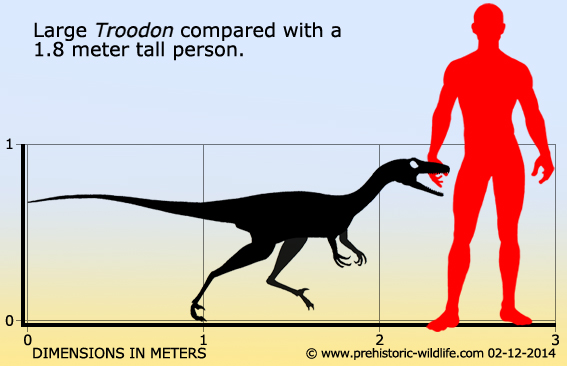

2 - Troodon

Troodon was a relatively small dinosaur without an especially powerful bite when compared to the other dinosaurs on this list; however it did have several things going for it that the others here did not. Studies and re-constructions of the brain have revealed that it was beginning to show the signs of folding, where more neural cells are packed into the same area that allows for more efficient brain functions. Second is the large size of the brain in relation to this dinosaur’s size, a controversial subject, but one that is not entirely without its merits. Third are the large forward facing eyes that would have allowed for exceptional stereoscopic vision even in low light conditions. Fourth and final is that one of the fingers was semi opposable to the others which on paper suggests that Troodon was better able to manipulate small objects, and interact with its environment. Had the mass extinction of dinosaurs not taken place at the end of the Cretaceous, dinosaurs like Troodon may have evolved to become the most intelligent life forms on the planet.

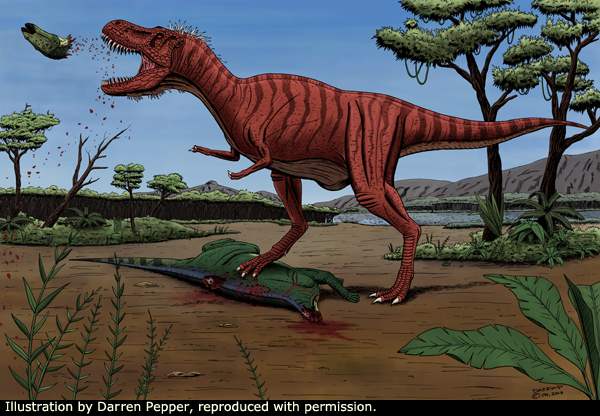

1 - Tyrannosaurus

This

dinosaur hardly needs any introduction as it is more famous than any

other prehistoric animal. Tyrannosaurus was the

pinnacle of large

theropod dinosaur evolution that was cut short by the mass extinction

of the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous. Although no longer

considered to be the largest (Spinosaurus and Giganotosaurus

are

usually credited as being bigger) Tyrannosaurus

was possibly the

stronger with an incredible bite force and teeth designed for punching

through and crushing the bones of any other dinosaur. Whereas other

dinosaurs may have had to close their mouths around prey several times

to deliver a series of weakening bites, Tyrannosaurus

only had to

bite once.

In

the past Tyrannosaurus has been accused by some of

being just a

scavenger for a number of reasons that mostly connect to its

differences to other meat eating dinosaurs. Today however the idea

that Tyrannosaurus was only a scavenger is politely

put considered

extremely unlikely, and it is seen as a meat eater that primarily

hunted for its own food, but would also steal kills from other

predators and scavenge just like almost every other predator that ever

lived. More details about the arguments for and against the

scavenging theory are on the main Tyrannosaurus

page.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|