Vulcanodon

Name:

Vulcanodon

(Volcano tooth).

Phonetic: Vul-can-o-don.

Named By: Michael Raath - 1972.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria,

Saurischia, Sauropodomorpha, Sauropoda, Gravisauria,

Vulcanodontidae.

Species: V. karibaensis

(type).

Diet: Herbivore.

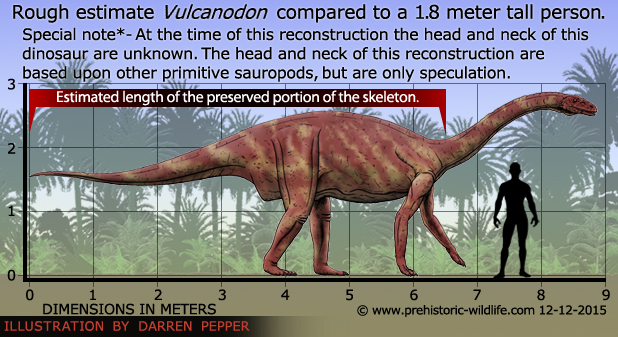

Size: Holotype individual dimensions include

following; Fore leg - humerus 70 centimetres, radius 64.7 centimetres,

ulna 66 centimetres. Hind leg - Femur 110 centimetres, tibia 63.4

centimetres. Total length of preserved portion of the skeleton

estimated at 6.5 meters, however this figure does not include the neck

and skull. Total size uncertain until neck vertebrae are found, but

certainly longer than 6.5 meters.

Known locations: Zimbabwe, Lake Kariba, Island

126/127 - Vulcanodon Beds Formation.

Time period: Toarcian of the Jurassic (see main

text for more detail).

Fossil representation: Partial but articulated post

cranial remains, including pelvis, limbs and vertebrae.

Vulcanodon

is easily one of the more popular dinosaur genera, and one that has

had a number of ‘firsts’ attributed to it. However, our

understanding of this genus and changed considerably since it was first

described in 1972. The name Vulcanodon means

‘volcano tooth’

and is a reference to the discovery of Vulcanodon

between two

Jurassic aged lava beds (long cooled down). The word volcano is

derived from the latin vulcano, which in turn is derived from

Vulcanus, more commonly known in English as Vulcan, the ancient

Roman god of fire.

The

post cranial remains of Vulcanodon were first found

in 1969 by B.

A. Gibson on a small Island in Lake Kariba of Zimbabwe (at the

time known as Rhodesia). Lake Kariba is actually an artificial lake

and reservoir created by the construction of the Kariba Dam, and the

location where the fossils were found is simply known as Island

126/127. The remains were collected over the course of three

expeditions in October 1969, and March and May 1970. Later in

1970 brief notes about the fossils were presented to a symposium in

Cape Town, South Africa. No more public information about the

fossils appeared until their formal scientific description was

released in 1972.

When

first described by Michael Raath in 1972, Vulcanodon

was marked

down as a prosauropod

(in more modern terms, a sauropodomorph)

dinosaur on the basis of the form of the pelvis and the teeth, the

latter of which were suited to processing meat and hence indicating an

omnivorous diet. The original explanation for these teeth being found

at the pelvis was relocation from a death pose commonly seen in

dinosaur remains. This is caused by the contraction of the tendons in

the neck after death and during decomposition which causes the neck and

head to arc backwards to look like they are curving over the back.

These teeth however are now known to have been left behind by a

theropod dinosaur and not the Vulcanodon, and

were most likely left

behind when said theropod was feeding upon the body of the Vulcanodon.

The

pelvis of Vulcanodon is very much like those of

sauropodomorph

dinosaurs, though in this case it also seems to have been a

proverbial ‘red herring’. The true nature of Vulcanodon

being a

sauropod

was indicated in a 1975 paper by Arthur Cruickshank who noted

that the fifth metatarsal (one of the foot bones) is the same

length as the others,a feature seen in sauropods, not

sauropodomorphs. With this more attention was given to the other

parts of the skeleton, and with the exception of the pelvis,

everything fitted a sauropod body form. Today, Vulcanodon

is

recognised as a potentially transitional sauropod which gives us some

clues as to how sauropodomorphs evolved a larger, quadrupedal body

form to become the first sauropods, the pelvis being an archaic

feature that had remained in Vulcanodon, but

would disappear from

later sauropod forms.

With

Vulcanodon now correctly described as a sauropod,

it became

recognised as the earliest known appearance of a sauropod dinosaur.

This is because the fossil bed that the Vulcanodon

holotype was

found in was believed to date to the early Hettangian, possibly the

Triassic/Jurassic boundary. Two things have happened since this time

though which now tell us that Vulcanodon was not

the first sauropod to

appear on the face of the planet. The first is rather simply the

2000 description of Isanosaurus

from Thailand, which is a sauropod

known to have lived around the Norian/Rhaetian stages of the Triassic,

comfortably before the Hettangian stage of the Jurassic. The second

is a study conducted by Adam Yates in 2004 that covered the lava

beds that Vulcanodon was found in. These beds

cannot be accurately

dated with radiometric techniques, but the weathering upon them

indicates that they are of the same age as other lava beds in the Karoo

Basin which were laid down over a course of about one million years

during the Toarcian period of the Mid Jurassic. This study then means

that the Vulcanodon genus roughly lived about one

hundred and eighty

million years ago (give or take a few million years) instead of

about two hundred and forty-five million years ago. Given the slight

mix of sauropodomorph features such as the pelvis, and Vulcanodon

may

even be a late surviving transitional form.

When

Vulcanodon was realised to be sauropod, and at the

time thought to be

a very early one, palaeontologists considered the possibility of

creating a new group of sauropods. This finally happened in 1984

when Michael Cooper created the Vulcanodontidae. This group was

primarily centred around Vulcanodon as the type

genus, hence the name

usage, and Barapasaurus

from India, though the genera

Zizhongosaurus

and Ohmdenosaurus

have also been included within this

group by others. The first problems started with Zizhongosaurus

and

Ohmdenosaurus which are known from remains that are

so fragmentary that

not all palaeontologists are convinced about the validity of these

genera. This left Vulcanodon and Barapasaurus

together, but then

in 1995 a study by Paul Upchurch revealed that Barapasaurus

was

quite a bit more advanced than Vulcanodon, and

therefore cannot be

kept in the same group. This left Vulcanodon all

on its own, and

since you need more than one of anything to have a group, the

Vulcanodonidae fell into disuse by the majority of palaeontologists.

Then

in 2004 a new genus of sauropod called Tazoudasaurus

was named from

fossils discovered in Morocco. Also known from partial remains,

Tazoudasaurus is noted for only really differing

from Vulcanodon only

in the form of the vertebrae. This has not only led to suggestions

that Tazoudasaurus and Vulcanodon

are closely related, but it has

also seen some (but at the time of writing not all)

palaeontologists recognising the Vulcanodontidae as a valid group

again, This time with Vulcanodon and Tazoudasaurus

as the main

genera, but occasionally also seeing the inclusion of Zizhongosaurus

again, though this genus is still considered dubious by many. One

of the signature features of sauropod genera in this group is that

members must have a particularly narrow sacrum, the part of the hip

where the sacral vertebrae are sandwiched between the ilium bones.

As

a living dinosaur, Vulcanodon would have been a

very small sauropod

dinosaur, and one that would not be classifiable with the ‘true

sauropods’ that would soon become the dominant sauropod form a little

later in the Jurassic. This is not to say that Vulcanodon

was not a

sauropod, it was, just that the sauropods are broken down into

groups for easier classification amongst genera, and Vulcanodon

is

considered to be too primitive to be grouped with forms such as

Cetiosaurus

and Apatosaurus.

Although

not perfectly adapted to a quadrupedal posture, Vulcanodon

almost

certainly went about in one. The fore limbs are three quarters of the

length of the hind limbs, meaning that the back would have been

vertically level to maybe slanting slightly down towards the neck.

Vulcanodon also had a claw on the hallux (first

toe) of the foot,

another feature common to sauropodomorphs, but the second and third

toes of Vulcanodon had claws that were wider than

they were long.

At the time of writing these foot claws are only seen in Vulcanodon

and Tazoudasaurus.

Analysis

of the fossil location of Vulcanodon suggests that

in life these

sauropods lived in very arid environments, possibly feeding upon the

plants that sprang up around watering holes or perhaps feeding

excessively during wet seasons and surviving more upon fat reserves

during the dry season. This is of course presuming that the body was

not deposited to said environment by means of seasonal flood water,

but only the discovery of new Vulcanodon fossils

and analysis of their

fossil sites can find that out.

Vulcanodon

is often quoted as being six and a half meters long, but this is

actually the estimated length of the preserved portion of the skeleton

which does not include the neck or skull. How long Vulcanodon

was

specifically would depend upon the length of the neck, which until

further fossils are found, can only really be guessed at. Still, Vulcanodon

was

certainly within the predatory scope of the larger theropod dinosaurs

of the time, possibly those like Berberosaurus,

remains of which

were found nearby Tazoudasaurus further North in

Morocco. It is not

known what genus the theropod teeth found with the Vulcanodon

fossils

belonged too, but they do reveal the presence of meat eating

dinosaurs where the body of this individual Vulcanodon

came to rest.

Further reading

- Fossil vertebrate studies in Rhodesia: a new dinosaur

(Reptilia, Saurischia) from near the Triassic-Jurassic boundary

- Michael Raath - 1974.

- A reassessment of Vulcanodon karibaensis Raath

(Dinosauria:

Saurischia) and the origin of the Sauropoda - Michael R.

Cooper - 1984.

- The Evolutionary History of Sauropod Dinosaurs - Paul Upchurch

- 1995.

- First record of a sauropod dinosaur from the upper Elliot

Formation (Early Jurassic) of South Africa - Adam M. Yates,

John P. Hancox, Bruce S. Rubidge - 2004.

- Integrating ichnofossil and body fossil records to estimate

locomotor posture and spatiotemporal distribution of early sauropod

dinosaurs: a stratocladistic approach - Jefferey A. Wilson -

2005.

- Anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Tazoudasaurus

naimi

(Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the late Early Jurassic of Morocco

- Ronan Allain, Najat Aquesbi - 2008.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|