Plesiosaurus

Name:

Plesiosaurus

(Almost lizard).

Phonetic: Pleh-see-oh-sore-us.

Named By: William Conybeare & Henry De la

Beche - 1821.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia,

Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria, Plesiosauroidea, Plesiosauridae.

Species: P. dolichodeirus

(type).

Diet: Piscivore.

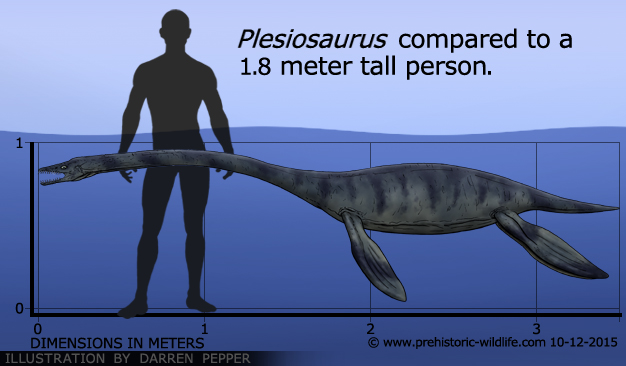

Size: Approximately 3.5 meters long.

Known locations: England - Lias Group.

Time period: Possibly late Rhaetian of the Triassic

through to Sinemurian of the Jurassic.

Fossil representation: Many specimens.

First

and most famous member of the plesiosaur

group, Plesiosaurus

caused

a stir upon its discovery as nothing like it was previously known.

Unfortunately Plesiosaurus suffered from the

wastebasket taxon effect

as any set of remains remotely similar to it ended up being

assigned to the genus without much further thought (a method of

classification that also affected many other prehistoric animals such

as the dinosaur Megalosaurus

and the pterosaur Pterodactylus).

Later study of Plesiosaurus fossils would reveal

that many of these

remains actually represented completely different plesiosaurs. New

plesiosaur genera created from the re-classification of plesiosaurus

species include Hydrorion

and Seeleyosaurus. Some fossils of Plesiosaurus

were renamed as the genus Occitanosaurus, but that

genus has now been

synonymised with Microcleidus.

How

long Plesiosaurus spent in the water has long been

a matter of debate.

Classical art and reconstructions from the early years of marine

reptile palaeontology depicted it as being just as capable of walking

about on land as it could swim in the ocean. Also the long neck was

almost always depicted as shooting out from the water and arcing around

in strong curves, but today both of these depictions are thought to

be highly unlikely.

The

limbs of Plesiosaurus which were once legs in its

ancestors have

evolved into flippers which are actually quite stiff. This makes them

better for paddling through the water, but cumbersome on land, and

certainly not likely to be capable of lifting Plesiosaurus’s

body off

the ground. At best Plesiosaurus would be capable

of pulling its body

with the front flippers while pushing with the rear. This may make it

capable of leaving the water but not for any great distance inland.

Possibly more likely is Plesiosaurus pushing

itself through the

shallows where the water was not deep enough to float its entire body

but still capable of supporting some of the weight and the bulk so that

the flippers did not have to ‘lift’ as much.

The

construction and makeup of the neck itself is actually taken as the

strongest evidence for an entirely if not almost entirely aquatic

lifestyle. Long presumed by many people to be capable of bending in

strong curves, reconstruction of the vertebrae has revealed that the

neck was surprisingly inflexible with only gentle arcs along the entire

length of the neck being possible. This means that the neck was most

stable when projecting horizontally level forwards. This also means

that Plesiosaurus probably could not carry its head

and neck high off

the ground should it ever leave the water, and if it ever did the

head and neck may have had to be rested on the ground to support the

weight and bulk which the neck muscles were incapable of doing without

the buoyant support of surrounding water.

It’s

most likely that the neck was long in order to afford Plesiosaurus

additional reach to strike out at prey. Given the necks inherent

weakness and inflexibility the older theories depicting Plesiosaurus

shooting its head and neck into the air and arcing down onto a shoal of

fish are no longer considered accurate. Instead Plesiosaurus

may have

approached prey from the side or even below, hiding its large body in

the murk of the lower depths so that fish did not realise the danger.

The latter theory is often proposed for the elasmosaurid group of

plesiosaurs that had the proportionately longest necks of all the

plesiosaurs.

If

Plesiosaurus was capable and if so how long it spent

on land has also

been part of the argument of whether it laid eggs or gave birth to live

young. Plesiosaurus may have struggled its way up

a beach like

turtles do today, possibly even using a high tide to carry it as far

up the shore as it was able to reach and then laying eggs in the sand

just beyond the tidal reach. Such behaviour would have been risky as

Plesiosaurus would likely need the tides to carry it

back out to sea,

and may have been vulnerable to terrestrial predators in the process.

While

the above is a viable theory, it needs to be remembered that the

precedent for live birth exists in other marine reptiles, and may go

back to the plesiosaur ancestors the nothosaurs,

as indicated by

potential fossil material of the small nothosaur Lariosaurus.

If live

birth is the case for Plesiosaurus, then it’s a

reasonable

proposition that it may never have ventured onto land and spent its

entire life in the water.

Further reading

- A revision of the classification of the Plesiosauria with a synopsis

of the stratigraphical and geographical distribution of the group -

Lunds Universitets �rsskrift, N. F. Avd. 2. 59, 1-59 - P. O. Persson -

1963.

- The English Upper Jurassic Plesiosauroidea (Reptilia) and a review of

the phylogeny and classification of the Plesiosauria - Bulletin of the

British Museum (Natural History) 35(4):253-347 - D. S. Brown - 1981.

- Dorsal nostrils and hydrodynamically driven underwater olfaction in

plesiosaurs - Nature, 352, 62-64 - A. R. I. Cruickshank, P. G. Small

& M. A. Taylor - 1991.

- Morphological and taxonomic clarification of the genus Plesiosaurus

-

G. W. Storrs - 1997 - In Ancient Marine Reptiles 145-190 - J. M.

Callaway & E. Nicholls (eds).

- Reevaluation of the holotype of Plesiosaurus (Polyptychodon)

mexicanus, Wieland, 1910 from the Upper Jurassic of

Mexico: a

thalattosuchian, not a sauropterygian - Revista Mexicana de Ciencias

Geol�gicas 25(3):517-522 - M. -C. Buchy - 2008.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|