Terminonatator

Name:

Terminonatator

(Last swimmer).

Phonetic: Ter-min-o-nay-tay-tor.

Named By: Tamaki Sato - 2003.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia,

Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria, Elasmosauridae.

Species: T. ponteixensis

(type).

Diet: Piscivore.

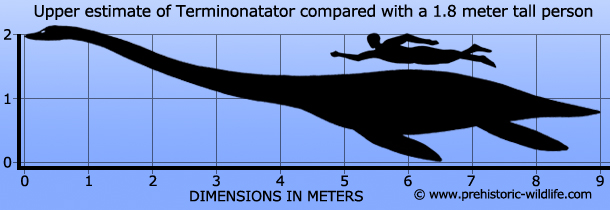

Size: Estimated at 7 meters long. Possibly

9 meters long if it had a neck of proportionate length to some other

elamosaurids. Skull is 26.8 centimetres long.

Known locations: Canada, Saskatchewan -

Bearpaw Formation.

Time period: Campanian of the Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: Skull and partial articulated

skeleton, possibly of a sub adult.

With

remains that were found in Campanian age rocks Terminonatator

was

possibly one of the last elasmosaurid plesiosaurs to swim in the

ocean. This is a far cry away from the Jurassic heyday of the

plesiosaurs when they were one of the most common types of marine

reptile in the ocean. In the Jurassic plesiosaurs had to contend with

being hunted by large pliosaurs such as Pliosaurus

and Kronosaurus,

but the Late Cretaceous waters of the Western Interior Sea Way which

submerged large portions of central North America were probably even

more dangerous. Here Terminonatator would have

had to contend with

mosasaurs like Tylosaurus

which was possibly larger and faster than the

previous pliosaurs, as well as large sharks such as Cretoxyrhina

which seem to have eaten anything in front of them, including

marine reptiles.

Evidence

for how dangerous these waters were comes from the right thigh bone of

Terminonatator which was broken but managed to

heal. It is uncertain

how this injury occurred but could quite possibly have been caused by

an impact with another marine reptile. On a related note the femur

(upper leg bone) of the rear flippers is longer than the equivalent

humerus (upper arm bone) of the front flippers, which is

different to the usual elasmosaurid configuration. It remains

uncertain what effect a more developed set of rear limbs would have had

on swimming, but it may have allowed for a more powerful stroke which

could have granted Terminonatator a boost in speed

and possibly

manoeuvrability, both making it easier for Terminonatator

to evade

predators.

The

skull of Terminonatator displays most of the

typical elasmosaurid

features of prey capture; typically long conical teeth that

intermeshed together when the jaws were closed. Seventeen to eighteen

teeth were in the each side of the dentary (lower jaw), while at

least thirteen teeth were in each side of the maxilla (main upper

jaw). The premaxilla (front of the upper jaw) had nine teeth,

but without further specimens it is impossible to say if this is

typical of the genus or just the individual. Together this means that

Terminonatator had around sixty-nine to

seventy-one teeth in its

mouth, although the actual figure may still have been a little higher.

The

overall appearance of the skull and lower jaw for Terminonatator

is

quite unique compared to other elasmosaurids. The snout was quite

short compared to other elasmosaurid plesiosaurs and the pineal

foramen, a hole in the skull where a light sensitive organ is

sometimes found in reptiles is completely closed. This suggests that

Terminonatator did not rely upon sensing the

direction of the light

above which raises the question of was it nocturnal? Without the

scleral rings of the eyes it would be impossible to say if were

nocturnal or not, but by being so Terminonatator

might have been able

to avoid the larger predators of the day, possibly explaining why it

was still managing to stay alive when the plesiosaurs and particularly

elasmosaurids had greatly declined in numbers.

The

lower jaw of Terminonatator also has an extended

coronoid process, a

bone that rises from the lower jaw into the skull and serves as an area

for muscle attachment. A more developed bone suggests a more

developed muscle system that may not necessarily mean a stronger bite

but a faster one. A shorter snout would also reduce resistance when

opening in the water which could have increased jaw opening times.

Fast jaw opening and closing could mean a specialisation in hunting

faster moving fish, with a speed boost from slightly more developed

rear limbs helping in the pursuit of prey. Unfortunately the rear

portions of the skull of the holotype are damaged and incomplete and as

such it is difficult to infer the full workings of the skull with

accuracy.

Despite

the incompleteness of the skull however, partial impression of the

brain have been found, giving palaeontologists a rare glimpse at

elasmosaurid biology. One area that stands out seems to be a

well-developed olfactory area. This connects to a wider theory about

how marine reptiles could sniff the water to pick up smells that were

drifting in the currents and how some marine reptiles are thought to

have had directional smell that helped them to locate things like prey.

The

actual size of Terminonatator is still something

that is not known as

an absolute as there are two main factors to consider. The type

specimen of Terminonatator has vertebrae that are

fused to the neural

arches, something which is taken to suggest that it had reached

adulthood. However other parts of the skeleton that should be fused

are not which suggests that this specimen of Terminonatator

may in fact

be a sub adult that had reached almost adult size, but still had bit

to go yet. The second thing to consider is the true length of the

neck. If Terminonatator had an exceptionally long

neck similar to

that seen in some like Mauisaurus

then it may have been even longer

with a total length of nine rather than the seven meters usually

attributed to it. However it’s worth remembering that this extra

length would just be extra neck and that Terminonatator

would still be

towards the smaller end of the elasmosaurid size scale.

Plesiosaurs

are thought to have swallowed gastroliths, and clear evidence for

this can be seen in the Terminonatator holotype

which has over

one-hundred and fifty pebbles (some six centimetres across) which

were found inside the stomach area of the body. While these pebbles

would have weighted Terminonatator down in the

water so that it was

neutrally buoyant, another main reason for these stones would have

been to aid digestion. You must realise that while the sharp teeth of

Terminonatator were excellent for catching prey like

fish, they could

not cut through flesh and so fish would have likely been swallowed

whole. The grinding action of the stones in the stomach would have

helped with the digestion of this fish, and further support for this

comes from ground up fish bones amongst the gastroliths in the belly of

a specimen of an elasmosaurid called Styxosaurus.

The

type species name of T. ponteixensis means

‘from Ponteix’, the

town near where the remains were recovered.

Further reading

- Terminonatator ponteixensis, a new elasmosaur (Reptilia:

Sauropterygia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Saskatchewan. - Journal of

Vertebrate Paleontology 23(1):89-103. - Tamaki Sato - 2003.

Random favourites

|

|

|

|