Styxosaurus

Name:

Styxosaurus

(Styx lizard).

Phonetic: Sticks-oh-sore-us.

Named By: Samuel Paul Welles - 1943.

Synonyms: Alzadasaurus kansasensis,

Alzadasaurus pembertonii, Cimoliasaurus snowii, Elasmosaurus

snowii, Thalassiosaurus ischiadicus, Thalassonomosaurus marshi.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia,

Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria, Elasmosauridae.

Species: S. snowii (type), S.

browni.

Diet: Piscivore.

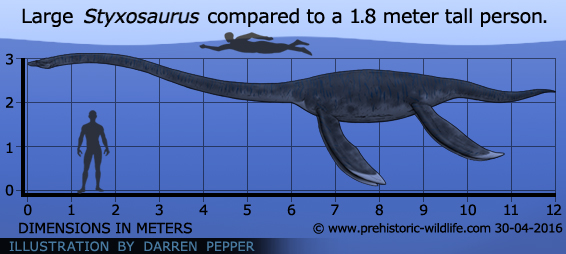

Size: 11 to 12 meters long.

Known locations: USA, Kansas, and South Dakota.

Time period: Santonian to Campanian of the

Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: At least two specimens.

The first specimen of Styxosaurus was of a skull and twenty cervical (neck) vertebrae, but was initially described as a species of Cimoliasaurus (C. snowii) by Samuel Wendell Williston in 1890. Williston then shifted it over as a species of Elasmosaurus in 1906 as E. snowii. Later study by Samuel Paul Welles led to the material being used to create the new genus of Styxosaurus, naming it after the river that in Greek Mythology separated the underworld from the land of the living. A second and more complete elasmosaurid skeleton was described by Welles and James Bump as a new species Alzadasaurus pembertoni in 1949. However later study by Ken carpenter in 1999 found that it was actually another specimen of Styxosaurus. The transferal of fossil material has not always been towards Styxosaurus however, as a second species named S. browni (named by Welles in 1952) was later found to be a specimen of Hydralmosaurus.

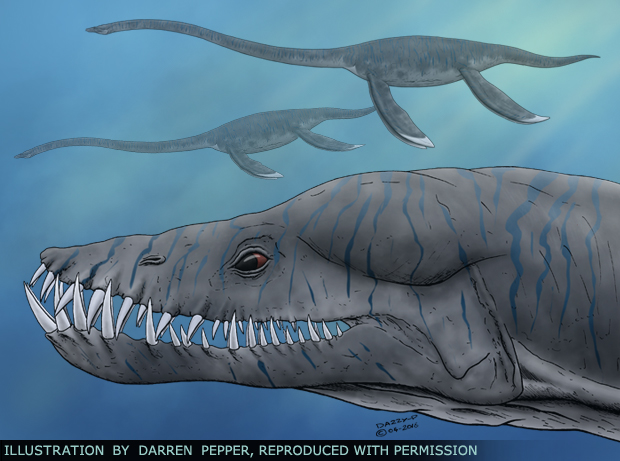

Like

other elamosaurid plesiosaurs

Styxosaurus had a

very long neck that

accounted for up to half its body length. This neck is thought to

have been the primary feeding adaptation which allowed Styxosaurus

to

reach into shoals of fish. An increasingly popular theory is that

elasmosaurids like Styxosaurus may have approached

fish from beneath so

that they could use the murk of deeper waters to hide their bodies

while they presented a small profile of the front of the head to the

prey. Such behaviour would greatly reduce the chance of being

spotted by the prey that Styxosaurus was

stalking, increasing

the chance of a successful hunt. Styxosaurus also

had the typical

sharp thin teeth that intermeshed together when the jaws closed so that

there was absolutely no escape for any fish caught between them.

Like

many other marine reptiles like it, Styxosaurus

has been found with a

large number of gastrolith stones within its body. The swallowing of

stones by plesiosaurs has long been interpreted as an attempt to

counter the lifting effect of the air in the lungs so that the

individual could swim more easily below the surface. Today though

things are not so clear cut as this Styxosaurus

specimen actually has

fish bones which look like they have been ground by the stones. This

fits in with the type of teeth in the mouth of Styxosaurus

which are

perfectly adapted for seizing fast and slippery prey, but next to

useless for cutting through flesh. This means that after prey was

swallowed whole, the stones would rub off things like scales so that

the flesh could be digested as well as the remaining bones being ground

and broken up. Additionally the weight of the gastroliths when

measured resulted in a combined weight that was but a tiny fraction of

the total weight of the living animal. With this in mind it seems

reasonable that the primary function of the gastroliths in Styxosaurus

and other plesiosaurs was to help with digestion, while any

additional effect of the stones providing increased ballast was more of

a secondary benefit.

Though

predatory, Styxosaurus, especially smaller

juveniles would have been

vulnerable to larger sharks

such as Cretoxyrhina

and Cardabiodon,

while

the emerging mosasaurs

would become the top predators of the seas, and

even threaten adult Styxosaurus.

Further reading

- Structure of the Plesiosaurian Skull. - Science 16 (405): 262. - S.

W. Williston - 1890a.

- North American plesiosaurs: Elasmosaurus, Cimoliasaurus,

and

Polycotylus. - American Journal of Science Series 4

21: 221–236. - S.

W. Williston - 1906.

- Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs with description of new material from

California and Colorado. - Memoirs of the University of California

13:125-254. - S. P. Welles - 1943.

- Revision of North American elasmosaurs from the Cretaceous of the

western interior. - Paludicola 2(2):148-173. - K. Carpenter - 1999.

- Gastroliths associated with plesiosaur remains in the Sharon Springs

Member of the Pierre Shale (Late Cretaceous), western Kansas. -

Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 103(1-2): 58-69. - M. J.

Everhart - 2000.

- Taxonomic reassessment of Hydralmosaurus as Styxosaurus:

new insights

on the elasmosaurid neck evolution throughout the Cretaceous. - PeerJ

4:e1777. - R. A. Otero - 2016.

Random favourites

|

|

|

|