Protosphyraena

Name:

Protosphyraena

(Early Sphyraena).

Phonetic: Pro-to-s-fy-ray-nah.

Named By: J. Leidy - 1857.

Classification: Chordata, Osteichthyes,

Actinopterygii, Pachycormiformes, Pachycormidae.

Species: P. perniciosa, P.

bentoniana, P. nitida.

Diet: Piscivore/Carnivore.

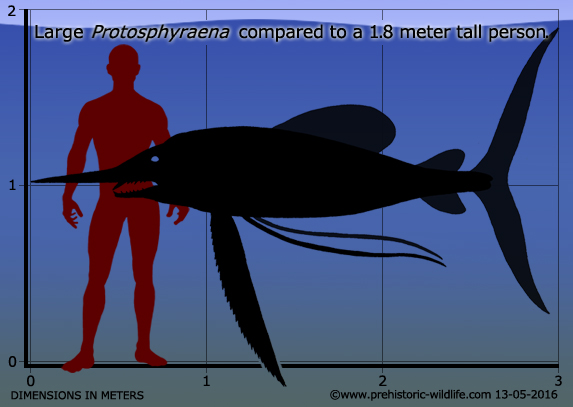

Size: Specimens range in size beween 2 and 3

meters in length. Largest known species is P. perniciosa.

Known locations: Canada, Manitoba - Vermilion

River Formation, Saskatchewan - Ashville Formation. England

- West Melbury Marly Chalk Formation. France. Jordan. Spain

- La Cabana Formation. USA, Alabama - Mooreville Chalk

Formation, Colorado - Greenhorn Limestone Formation, Kansas

- Greenhorn Limestone Formation, Niobrara Formation, South

Dakota - Greenhorn Limestone Formation, Texas - Eagle Ford

Formation.

Time period: Most fossils range from the Cenomanian

to the Santonian of the Cretaceous, though some fossils are now

confirmed as being Campanian in age.

Fossil representation: Remains on multiple

individuals ranging from partial jaws, snouts and teeth, but

partial post cranial skeletons are also known.

Protosphyraena

means ‘early Sphyraena’, a reference to the

Sphyraena genus

which includes the modern day barracuda. This all came down to the

original interpretation of the first fossils which were very much like

those of barracuda. However, later fossil examples of

Protosphyraena revealed it to be more swordfish-like

in appearance,

though it must be noted that today Protosphyraena

is not considered to

be a relative of either barracuda or swordfish.

Protosphyraena

is a predatory fish that was built for high speed, either steady

cruising or sudden bursts after prey. The body is long and

streamlined with high forks to the tail that provide an efficient large

area to push against the water. The pectoral fins are also very long

as well which is also an indicator of high swimming speeds as they act

as hydroplanes to keep the body level when swimming forward. The

faster the movement forward, the larger the pectoral fins need to be

to counter this effect.

Aside

from acting as hydroplanes, the pectoral fins of Protosphyraena

may

have also been killing weapons in their own right. The fins of

Protosphyraena perniciosa particularly were

reinforced with a hard

keratinous substance, could grow to over a meter in length and also

had a serrated edge on the anterior (frontal) plane. They would

for a lack of a better term been almost like a pair of swords.

Protosphyraena

also had a long yet robustly formed snout and under this a mouth which

housed large, forward pointing teeth. One popular view of

Protosphyraena hunting is that it rammed into the

flanks of large

aquatic creatures (much like as has been speculated for the ancient

shark Edestus)

like mosasaurs,

as postulated in the Hunting

Dinosaurs on the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada by

Charles

Sternberg. In this example Protosphyraena would

spear the animal with

its snout, burying its head up to its eyeballs while lashing at the

sides with its sword-like pectoral fins.

As

dramatic as that sounds, it perhaps is not very likely, after all

mosasaurs themselves were predators, and while smaller ones like

Platecarpus,

may have been threatened by such fish, especially if

hunting in shoals, larger ones like Tylosaurus

would be more inclined

to take the opportunity of a quick snack. Modern sword fish use their

long snouts to lash out at fish, stunning and wounding them so that

they cannot swim away, and while the snout of Protosphyraena

was not

as long as modern swordfish, it could still have been combined with

the pectoral fins to lash out at several fish in a ‘bait ball’ so

that a few injured ones could then be picked off.

It

should also be noted however that the pectoral fins between different

species of Protosphyraena differed in length and

form, with those of

P. nitida being notably shorter than those of P.

perniciosa. The

pectoral fins of P. perniciosa may have also

served a defensive

purpose, making it very difficult for an apex predator such as a

large mosasaur to swallow a Protosphyraena without

the fins getting

stuck in the throat.

Further reading

- On an extinct genus of saurodont fishes. - Proceedings of the

Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 24: 280–281. -

Edward Drinker Cope - 1873.

- On two new species of Saurodontidae. - Proceedings of the

Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 25:337-339. - Edward

Drinker Cope - 1873.

- Remarks on Saurocephalus and its allies. -

Transactions of the

American Philosophical Society 11: 91–95. - J. Leidy -

1857.

- A contribution to the knowledge of the ichthyic fauna of the Kansas

Cretaceous. - Kansas University Quarterly 7(1):22-29, pl.

I, II. - A. Stewart - 1898.

- Notice of three new Cretaceous fishes, with remarks on the

Saurodontidae Cope. - Kansas Univ. Quar. 8(3):107-112. -

A. Stewart - 1899.

- Biostratigraphic distribution of species of Protosphyraena

(Osteichthyes: Actinopterygii) in the Niobrara and Pierre

Formations of Kansas. - Proceedings of the Nebraska Academy of

Sciences and Affiliated Societies, 89th Annual Meeting, p.

51-52. - J. D. Stewart - 1979.

- The stratigraphic distribution of late Cretaceous Protosphyraena

in

Kansas and Alabama, Geology, by J. D. Wilson. In,

aleontology and biostratigraphy of western Kansas: Articles in honor

of Myrl V. Walker, Fort Hays Studies, 3(10):80-94. - M.

E. Nelson (ed).

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|