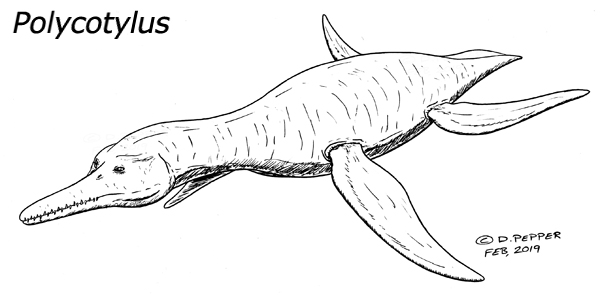

Polycotylus

Name:

Polycotylus

(very cupped vertebra).

Phonetic: Pol-e-cot-e-lus.

Named By: Edward Drinker Cope - 1869.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia,

Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria, Polycotylidae, Polycotylinae.

Species: P. latipinnis

(type), P. dolichops, P. ichthyospondylus, P.

ischiadicus, P. sopozkoi, P. suprajurensis, P. tenius.

In

addition to these, P. balticus, P. brevispondylus,

P. epigurgitis, P. orientalis, P. ultimus, P. donicus

are sometimes mentioned but these have all also been treated as nomen

dubia.

Diet: Piscivore/Carnivore.

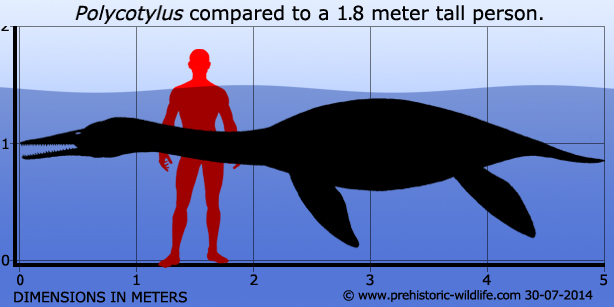

Size: Around 5 meters long, but size is

dependent upon species.

Known locations: Australia, North America and

Russia.

Time period: Late Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: Many individuals.

In

the early days of plesiosaur

evolution back in the Jurassic, there

were two main groups that were successful enough to become two of the

main kinds of marine reptiles of the Mesozoic. These were long necked

plesiosaurs such as Plesiosaurus

and Cryptoclidus,

and short necked

pliosaurs

(technically a sub group of plesiosaurs) such as

Pliosaurus

and Liopleurodon.

For a time these two groups were very

successful but by the later stages of the Mesozoic, both groups had

waned with the short necked pliosaurs becoming particularly rare.

It was now that a new kind of plesiosaur called a polycotylid emerged

to fill a void left by the disappearance of other marine reptiles

such as ichthyosaurs

that resulted in a body shape reminiscent of the

dwindling pliosaurs.

Polycotylus

is the type genus of the Polycotylidae, the family group of these new

kinds of plesiosaurs that appeared in the Cretaceous. Polycotylus

had

a body similar to those of its ancestors, though the key differences

between them are that Polycotylus had a much

shorter neck but longer

jaws. Whereas the long-necked plesiosaurs used their necks to gain a

reach advantage when hunting prey like fish, Polycotylus

relied more

upon speed and manoeuvrability to chase down its prey. Despite the

shorter neck however, Polycotylus still retained

a reasonably large

number of neck vertebrae. While this might have offered increased

flexibility for the neck, later polycotlids would develop similarly

proportioned necks but with a reduced number of vertebrae.

In

the 1980s a specimen of the type species P. latipinnis

(later

classified as LACM 129639) was found along with a foetus that was

about forty percent the length of its mother. This revealed two

things, the first being that plesiosaurs did give birth to live young

instead of laying eggs. This was not a huge revelation since most

palaeontologists were already of the opinion that plesiosaurs gave

birth to live young because of the difficulties they would have faced

when moving without the buoyancy of water to support their body

weight. Additionally their earlier relatives the nothosaurs

are also

known to have given birth to live young with such genera as Lariosaurus

and Keichousaurus.

The ichthyosaurs

are also known to have given

birth to live young, and even some modern reptiles such as sea snakes

and even the land living viviparous lizard (Zootoca vivipara)

give

birth to live young instead of laying eggs.

The

second is that plesiosaurs like Polycotylus almost

certainly employed a

K-strategy survival method when raising young. What this means is

that only a very small number of young are raised by an individual

throughout their lifetime, but the parent makes a long term

investment in raising and protecting the young so that they have a

better chance of making it to adulthood. This is a stark contrast to

the r-strategy method usually employed by reptiles we know today where

a large number of young are raised but are not given extended care and

protection by the parents. Not many young born this way survive to

adulthood, but the sheer numbers involved ensure the survival of the

species.

As

already mentioned, Polycotylus is the type genus

of the

Polycotylidae, and other plesiosaurs that are members of this include

Dolichorhynchops,

Edgarosaurus,

Eopolycotylus,

Palmulasaurus

and

Trinacromerum

amongst many others.

Further reading

- On some reptilian remains. - The American Journal of Science, series

2 48:278. - E. D. Cope - 1869.

- Notes sur les reptiles fossiles [Notes on fossil reptiles]. -

Bulletin de la Soci�t� G�ologique de France, 3e s�rie 4:435-444. - H.

-E. Sauvage - 1876.

- On the cranial anatomy of the polycotylid plesiosaurs, including new

material of Polycotylus latipinnis, Cope, from

Alabama. - Journal of

Vertebrate Paleontology 24 (2): 326–34. - F. R. O. Keefe - 2004.

- Plesiosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Turonian) Tropic

Shale of southern Utah, Part 2: Polycotylidae. - Journal of Vertebrate

Paleontology. 27 (1): 41–58. - L. B. Albright III, D. D. Gillette

& A. L. Titus - 2007.

-A New Species of the Plesiosaur Genus Polycotylus from the Upper

Cretaceous of the Southern Urals". Paleontological Journal. 50 (5):

494–503. - A New Species of the Plesiosaur Genus Polycotylus from the

Upper Cretaceous of the Southern Urals. - Paleontological Journal. 50

(5): 494–503. - V.M. Efimov, I.A. Meleshin & A.V. Nikiforov -

2016.

- Ontogeny of Polycotylid Long Bone Microanatomy and Histology. -

Integrative Organismal Biology. 1. - F. R. O’Keefe, P M Sander, T

Wintrich & S Werning - 2019.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|