Pachycephalosaurus

Name:

Pachycephalosaurus

(thick headed lizard).

Phonetic: Pak-ee-sef-ah-low-sore-us.

Named By: Barnum Brown & Erich Maren

Schlaikjer - 1943.

Synonyms: Tylosteus, Troodon wyomingensis.

Possibly also Dracorex and Stygimoloch

if these two genera do indeed represent juvenile forms.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria,

Ornithischia, Pachycephalosauridae, Pachycephalosaurinae,

Pachycephalosaurini.

Species: P. wyomingensis

(type).

Diet: Herbivore/Omnivore?

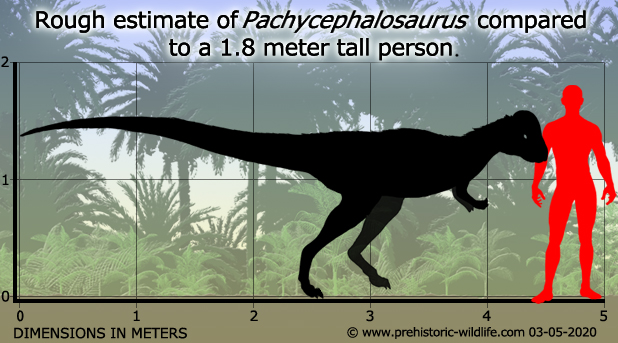

Size: Uncertain due to lack of remains, but

comparison to more complete genera has yielded estimates of around

4.5 meters long.

Known locations: USA.

Time period: Maastrichtian of the Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: Skull remains.

Once again one of the most famous dinosaurs of all time is actually represented by some of the most incomplete fossil material. To date Pachycephalosaurus is only represented by skull material; the actual appearance of the body so often seen in restorations is actually based upon the common form seen in more complete relatives. Although it may seem strange that a dinosaur genus based upon such few remains should become so popular, there are other very famous genera that are also based upon largely incomplete remains, with Ankylosaurus and Spinosaurus being just two such examples.

Pachycephalosaurus

as a dinosaur

The

reason why Pachycephalosaurus has persevered to

become one of the most

famous and best loved dinosaurs is because of the very thick dome

that grew on top of its skull. This dome grew to be made of bone

almost as much as twenty-five centimetres thick and seems to have grown

to protect the brain. This has led to the popular depiction of

Pachycephalosaurus head butting one another during

dominance contests

and possibly even head butting predators to defend themselves. This

supposed behaviour is also part of the reason why Pachycephalosaurus

has become so popular, though today it is an idea that has been

questioned.

The

biggest source of the controversy regarding the head butting theory for

Pachycephalosaurus comes from a 2004 study by

Goodwin and Horner,

though there are other detractors to the head butting theory. One of

the main concerns is that the bone structure of the dome is not

entirely solid but kind of spongy inside. Although this would have

certainly reduced the weight of the dome structure and subsequent

stress supporting it, it is believed that it would have effectively

crumbled under the force of successive blows. The shape of the dome

has also been criticised for not being the right form for effective

head on head blows and although the skeleton of Pachycephalosaurus

is

not known, its relatives are all known to have poor neck and back

support for initiating head on head blows.

Despite

these misgivings however there have been studies that have lent further

support to the idea that Pachycephalosaurus used

its head as a weapon,

such as Snivley and Cox in 2008, Lehman in 2010 and Snivley

and Theodore in 2011. These studies centre on new analysis of

Pachycephalosaurus skulls including biomechanical

models that indicate

that the heads would have been quite effective at delivering blows.

However it should be pointed out at this point that the vast majority

of palaeontologists who believe that Pachycephalosaurus

was a head

butter do not think that it butted head to head.

A

reasonable alternative to the head butting theory is actually the flank

butting theory. What this means is that rather than bash heads, two

Pachycephalosaurus would square up to one another

and then try to use

their heads to hit each other in the sides of the body. This idea is

more popular amongst palaeontologist because it gives some explanation

as to the form of the dome while also taking into account its apparent

lack of suitability for striking hard objects.

Therefore

the most commonly accepted scenario for Pachycephalosaurus

is that an

individual would start life with a flat head, and then have the skull

changing form into that of the dome like structure that we know. This

would signal the sexual maturity of an individual and serve as a visual

display with perhaps the largest and most developed domes belonging to

the most mature individuals. When visual signals and perhaps audial

calls did not work to settle the rivalry, two individuals struck each

other in the sides with their domed heads until one of them gave in

and conceded victory to the other.

Because

of the lack of skeletal remains it is hard to know much more than what

we already do about Pachycephalosaurus. The size

of the skull however

does actually indicate that Pachycephalosaurus is

the largest currently

known pachycephalosaurid.

The precise feeding behaviour of

Pachycephalosaurus is also uncertain because of the

very small teeth.

The jaws however are also short and end in a beak which might suggest

that Pachycephalosaurus was more of a selective

browser, only picking

off the parts of plants that were the most palatable.

Pachycephalosaurus has also been considered to have

included

invertebrates like insects into its diet. Pachycephalosaurus

is also

believed to have had very good vision, with large forward facing eyes

that would have allowed Pachycephalosaurus to have

stereoscopic

vision. What this means is that Pachycephalosaurus

would have had the

ability to effectively gauge distances in front of it with a high

degree of accuracy.

Classification issues

Today

Pachycephalosaurus is the type genus of the

Pachycephalosauridae,

which means that all dinosaur genera similar in form to

Pachycephalosaurus are referred to as

pachycephalosaurids (though

further sub-divisions can and are sometimes made depending upon the

context of the study). However when Pachycephalosaurus

was first

named it was actually described as a troodont, a member of the

troodontidae. The type genus of this group was Troodon,

a genus

that at the time of the description of Pachycephalosaurus

was only

known by teeth. These teeth were similar to those seen in what were

to become pachycephalosaurids, so it seemed correct at the time.

Later

in the in the twentieth century however, the teeth of Troodon

were

found to be a precise match for another dinosaur genus called

Stenonychosaurus,

a saurischian theropod that

although bipedal was

very different to pachycephalosaurids. With the realisation that

Troodon was not a pachycephalosaurid it could no

longer be used to

establish the type genus of the group. With the next genus name

having seniority technically being Pachycephalosaurus,

this genus

became the type used to establish the new group Pachycephalosauridae

in 1974.

In

the above paragraph it was stated that Pachycephalosaurus

has technical

seniority to be used as the type genus of the group. This is because

the oldest Pachycephalosaurus fossils were actually

first described

by Joseph Leidy in 1872 as a different genus called Tylosteus.

Tylosteus was based upon the description of what

would later be

identified as the squamosal bone from a Pachycephalosaurus

skull, but when

first described it was believed to have been a piece of dermal armour

from some kind of armoured reptile. Fast forward to the late

twentieth century and a new study of this bone by Donald Baird

revealed its real identity, but also raised a troubling prospect.

Under standard rules and procedures governed by the ICZN

(International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature) the first name

established usually has priority over any subsequent names; however

Baird actually managed to get a special exception made for

Pachycephalosaurus.

There

is a special clause where if it can be proven that the second name

for a genus has been in regular scientific use, while the first

name has not (in essence being almost forgotten) then an

application for protected status can be made for the second name. At

the time of this discovery Pachycephalosaurus was

already one of the

most popular dinosaurs talked about and was now the defining type

genus of the Pachycephalosauridae. Tylosteus was

virtually unknown

with perhaps only a handful of paleontologists and museum curators

knowing about it and none of them writing about it. For these reasons

the ICZN granted Pachycephalosaurus protected

status as a nomen

protectum (literally ‘name protected’) in 1985. Although this

is a very rare sequence of events, exactly the same argument was

successfully made for the most famous dinosaur genus of all time,

Tyrannosaurus,

when it was realised that Tyrannosaurus was

actually

the second name given to this genus.

Pachycephalosaurus

will remain a valid genus, however it is possible that other

pachycephalosaurid genera may end up getting absorbed into it.

The main two genera in question are Stygimoloch

named in 1983 and

Dracorex named in 2006. Neither Stygimoloch

nor Dracorex have the

large domes of the skull of Pachycephalosaurus,

but there is

compelling speculation that explains how all of these genera are

related. First of all, all three of these genera are known to have

lived at the same time and locations as one another. Dracorex

and

Stygimoloch are both represented only by the remains

of juveniles,

while Pachycephalosaurus however is only known by

the remains of

adults. Wider study of pachycephalosaurids in general seems to point

to a continuing trait where all juveniles had flat heads, while the

dome like structure seen in adults only developed when an individual

became fully mature. This is backed up by further study that the

bones of pachycephalosaurid skulls could change considerably in form as

an individual matured.

Unfortunately

while many palaeontologists are of the opinion that both Stygimoloch

and Dracorex should be regarded as juvenile Pachycephalosaurus,

there

are not currently any transitional fossil forms that could conclusively

prove this without doubt. To blur things even further, the

squamosal bone fragment once described as Tylosteus

has since been

considered to actually belong to Dracorex. If

correct then this would

make the protected name status for Pachycephalosaurus

unnecessary,

but it could also be a moot point if Dracorex is

indeed based upon

juveniles of Pachycephalosaurus.

Further reading

- A new species of troodont dinosaur from the Lance Formation of

Wyoming - Proceedings of the United States National Museum 79 (9): 1–6

- Charles W. Gilmore - 1931.

- A study of the tro�dont dinosaurs with the description of a new

genus and four new species, Barnum Brown & Erich Maren

Schlaikjer - 1943.

- New data on pachycephalosaurid dinosaurs (Reptilia: Ornithischia)

from North America - Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 25: 462–472 -

Peter M. Galton & Hans-Dieter Sues - 1983.

- Pachycephalosaurus Brown & Schlaikjer,

1943 and Troodon

wyomingensis Gilmore, 1931 (Reptilia, Dinosauria): Conserved

- Bulletin

of Zoological Nomenclature, 43 (1) - ICZN Opinion 1371 - 1986.

- Agonistic behavior in pachycephalosaurs (Ornithischia: Dinosauria): a

new look at head-butting behavior - Contributions to Geology 32 (1):

19–25 - Kenneth Carpenter - 1997.

- Cranial histology of pachycephalosaurs (Ornithischia:

Marginocephalia) reveals transitory structures inconsistent with

head-butting behavior - Paleobiology 30 (2): 253–267 - Mark Goodwin

& John R. Horner - 2004.

- Structural mechanics of pachycephalosaur crania permitted

head-butting behavior, E. Snivley & A. Cox - 2008.

- Extreme Cranial Ontogeny in the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur

Pachycephalosaurus - PLoS ONE 4(10) - J. R. Horner & M. B.

Goodwin - 2009.

- Pachycephalosauridae from the San Carlos and Aguja Formations

(Upper Cretaceous) of west Texas, and observations of the

frontoparietal dome, T. M. Lehmen - 2010.

- Common Functional Correlates of Head-Strike Behavior in the

Pachycephalosaur Stegoceras validum

(Ornithischia, Dinosauria)

and Combative Artiodactyls, E. Snivley & J. M.

Theodor - 2011. K. Carpenter. ed.

- Cranial Pathologies in a Specimen of Pachycephalosaurus

- In Farke,

Andrew A. PLoS ONE 7 (4) - J. E. Peterson & C. P. Vittore -

2012.

- Distributions of Cranial Pathologies Provide Evidence for

Head-Butting in Dome-Headed Dinosaurs (Pachycephalosauridae) - PLoS ONE

8(7) - J. E. Peterson, C. Dischler & N. R. Longrich - 2013.

- The early expression of squamosal horns and parietal ornamentation

confirmed by new end-stage juvenile Pachycephalosaurus

fossils from the

Upper Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation, Montana. - Journal of Vertebrate

Paleontology. 36 (2). - Mark B. Goodwin & David C. Evans -

2016.

Random favourites

|

|

|

|