Thescelosaurus

Name:

Thescelosaurus

(Wondrous lizard).

Phonetic: Fess-cul-o-sore-us.

Named By: Charles W. Gilmore - 1913.

Synonyms: Bugenasaura.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria,

Ornithischia, Thescelosauridae, Thescelosaurinae.

Species: T. neglectus, T. garbanii,

T. assiniboiensis.

Diet: Herbivore.

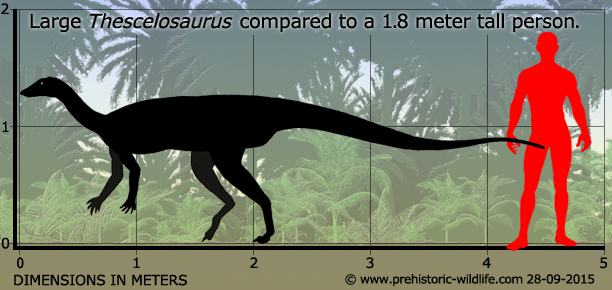

Size: Between 2.5 and 4 meters, depending

upon individuals/species. A particularly large specimen attributed to

T. garbanii has been identified as being 4.5

meters long.

Known locations: Canada, Alberta - Dinosaur

Park Formation, Oldman Formation, Scollard Formation,

Saskatchewan - Frenchman Formation, Ravenscrag Formation.

USA, Colorado - Laramie Formation, Montana - Hell Creek

Formation, Lance Formation, New Mexico - Fruitland Formation,

North Dakota - Hell Creek Formation, South Dakota - Hell

Creek Formation, Lance Formation, Wyoming - Lance Formation.

Time period: Maastrichtian of the Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: Many individuals in varying

states of completeness.

Thescelosaurus the Dinosaur

Thescelosaurus

seems to have been one of the main herbivorous dinosaurs roaming

around North America towards the end of the Cretaceous period. The

first fossils of Thescelosaurus began to be

recovered in the closing

decade of the nineteenth century, but were not described until

1913 by Charles W. Gilmore, who provided a much more detailed

description in 1915. For over a hundred years afterwards numerous

individuals of Thescelosaurus were recovered from

across the central

portion of North America, resulting in three distinct species being

named. One former genus called Bugenasaura has

also been discovered

to be a junior synonym to Thescelosaurus. Another

genus named

Parksosaurus

that in the past has been speculated to be synonymous with

Thescelosaurus, has in recent times been

re-affirmed as a distinct

genus.

Thescelosaurus

has often been described as a hypsilophodont, but modern analysis of

this dinosaur has found that Thescelosaurus is

actually quite different

from Hypsilophodon,

and therefore not likely related beyond both of

them being ornithopod dinosaurs. Like with most other ornithopod

dinosaurs, Thescelosaurus was a bipedal dinosaur

which had a body

counterbalanced by a long tail that accounted for much of the total

body length. Bizarrely for an ornithopod dinosaur, the upper leg of

Thescelosaurus was longer that the lower leg, the

complete opposite

to the arrangement seen in most other ornithopods. This meant that

Thescelosaurus would have actually been a relatively

slow runner.

This raises questions as to how Thescelosaurus

survived since there

are no other obvious defensive features on this dinosaur, yet we know

that Thescelosaurus became relatively widespread in

North America.

Scutes found in association with one Thescelosaurus

specimen may

indicate that at least one line of bony armour was present on the

body, however an alternative theory is that these scutes may have

come from a crocodile since these scutes have so far not been found

with any other individuals.

Numerous

individuals of Thescelosaurus are now known to us,

but there seems to

have been a wide variance in the sizes of adults which usually range

between two and half and four meters in length. Some of this

difference is likely down to a species level, with individuals of

T. garbanii often approaching four meters in

length, though one

specimen seems to have been at least four and a half meters long.

It’s possible though that Thescelosaurus may have

been sexually

dimorphic, meaning that there was a clear difference in how large

males and females grew.

Thescelosaurus

had pointed teeth at the front of the mouth and leaf shaped teeth

towards the back. Leaf shaped teeth like these are common in

herbivorous dinosaurs that feed upon softer plants as they easily slice

through leafy plant material. The pointed teeth are a little more

puzzling however, as they are not as well suited to an exclusive diet

of plants. This has led some to speculate that Thescelosaurus

might

have been omnivorous, either eating small animals like lizards or

occasionally scavenging carrion. Prominent ridges on the maxilla

bones of the skull and the observation that the leaf-shaped maxilla

teeth are set well inside the mouth support the idea that

Thescelosaurus had quite muscular cheeks to stop

food spilling out of

the sides of the mouth when processing food. Six pairs of small teeth

were also present in the pre-maxilla, though the tip of the

premaxilla was toothless to accommodate the horny beak that covered the

front of the mouth. This beak would have been the primary shearing

apparatus when cropping plants.

There

are two schools of thought concerning which kind of habitat

Thescelosaurus preferred. One is that Thescelosaurus

preferred

channel systems, feeding upon the banks of rivers and streams,

while another is that Thescelosaurus preferred

floodplains. It may

not sound like there is a lot of difference, and indeed the two

habitats are connected. Both have an abundance of plants that grow in

fertile soil, but channel systems feature a more regular growth of

plants where growth on floodplains can be more seasonal. Most

Thescelosaurus fossils have been dug out of

sandstone, which is more

a sign of a channel environment, whereas floodplains tend to produce

mudstone. There are also no mass bone beds of Thescelosaurus

individuals, again indicating a lack of flooding victims.

If

Thescelosaurus lived near water browsing upon softer

plants growing by

the water, then this may have also been an escape route for them when

they got attacked. As soon as a predator showed up they may have

entered and swum into and across the river, explaining why

Thescelosaurus did not retain leg proportions for

running, and also

how the genus came to be so widespread. Reduced limb proportions

would have also helped with locomotion through the water by not being

so easy to get tangled in underwater weeds and debris, and if the

latest reconstructions of Spinosaurus

are anything to go by, then

limb reduction in semi-aquatic dinosaurs may have been an easy thing to

achieve.

Thescelosaurus

lived during the latest stage of the Cretaceous and lived in the same

locations as hadrosaurs,

ceratopsians,

ankylosaurs,

pachycephalosaurs

and ornithomimids.

Predatory threats to

Thescelosaurus were many and included the famous tyrannosaurs

like

Tyrannosaurus,

to troodonts

like Troodon,

to one of the largest

dromaeosaurs,

Dakotaraptor.

Fossilised ‘heart’?

There

has been a lot of debate concerning a possible ‘heart’ believed to

have been fossilised in an individual Thescelosaurus

that was found in

1993. In a paper by Fisher et al published in 2000, they

described a fossilised structure found within a specimen of

Thescelosaurus that resembled a heart. Their

theory was that the

original heart muscle had been saponified (turned to soap) as a

result of anaerobic conditions and then through regular fossilisation

turned to geothite. The authors of this paper noted that the

‘heart’ was comparable with the heart of an ostrich with four

chambers, and that Thescelosaurus and probably

other dinosaurs had an

elevated metabolic rate closer to what we would term as warm-blooded.

It

was not long after that doubts about the interpretation of this

‘heart’ began to be publically voiced. The main problem that many

people had was that the ‘heart’ just did not look right with

anomalies in the basic structure. In a 2001 paper by Timothy et

al the ‘heart’ was re-interpreted as a simple concretion that had

simply built up an extra dense portion of sedimentary rock. It was

also noted that the ‘heart’ partially engulfed one of the ribs and

that a second similar concretion could be found behind the right leg.

Also observed was the part preserved as the aorta, the main blood

vessel that should carry oxygenated blood from the heart. Many noted

that this aorta actually became narrower where it actually joined the

‘heart’, something unprecedented in heart anatomy as this would

restrict blood flow. There were also no arteries branching off from

this aorta to take blood to other parts of the body. Despite these

observations, the original authors who described the ‘heart’

defended their earlier work, saying that the ‘heart’ was a

concretion, but one built up to the structure of the original heart

and aorta.

In

2011 a new study of the ‘heart’ by Cleland, Stoskopf and

Schweitzer used state of the art investigative methods including X-ray

diffraction, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, scanning electron

microscopy, histology and CT scanning to determine the truth of the

matter. Actually using computer modelling to ‘see inside’ the

‘heart’, they revealed that this structure did not have four

chambers like it was previously expected to. Instead they mapped out

three areas filled with less dense material than the surrounding

‘heart’ structure. Furthermore, these areas were completely

unconnected, which means in absolutely no way could they be heart

chambers, as heart chambers need to be connected so that blood can

flow through the heart.

The

2011 study also failed to find any of the common elements that are

found in fossilised remains of biological structures (i.e. carbon,

nitrogen, phosphorus). This means that this ‘heart’ was

composed of inorganic material that was not part of the original

dinosaur. There was however one patch where the impressions of soft

tissues identifiable at the cellular level were observed. These

impressions though do not reflect a heart structure, and were

recorded as simply being a case of a concretions pressing against soft

tissues and then preserving the form while hardening.

The

overall conclusion is that this structure is simply a concretion of

sand hardened to stone in such a way that at a glance it has become a

simulacrum of a heart, not the actual fossilised remains of one.

Further reading

- A new dinosaur from the Lance Formation of Wyoming. -Smithsonian

Miscellaneous Publications 61(5):1-5. - Charles W. Gilmore

- 1913.

- Osteology of Thescelosaurus, an orthopodus

dinosaur from the

Lance Formation of Wyoming. - Proceedings of the U.S. National

Museum 49 (2127): 591–616. - Charles W. Gilmore -

1915.

- Thescelosaurus warreni, a new species of

orthopodous dinosaur

from the Edmonton Formation of Alberta. - University of Toronto

Studies (Geological Series) 21: 1–42. - William A. Parks

- 1926.

- Classification of Thescelosaurus, with a

description of a new

species. - Geological Society of America Proceedings for 1936:

365. - Charles M. Sternberg - 1937.

- Thescelosaurus edmontonensis, n. sp., and

classification of

the Hypsilophodontidae. - Journal of Paleontology 14 (5):

481–494. - Charles M. Sternberg - 1940.

- Notes on Thescelosaurus, a conservative

ornithopod dinosaur from

the Upper Cretaceous of North America, with comments on ornithopod

classification. - Journal of Paleontology 48 (5):

1048–1067. - Peter M. Galton - 1974.

- Dinosaurs of the Lance Formation in eastern Wyoming, by Kraig

Derstler - In, The Dinosaurs of Wyoming. Wyoming Geological

Association Guidebook, 44th Annual Field Conference. Wyoming

Geological Association. pp. 127–146. - Gerald E. Nelson

(ed.) 1994.

- The species of the basal hypsilophodontid dinosaur Thescelosaurus

Gilmore (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda) from the Late Cretaceous of

North America. - Neues Jahrbuch f�ur Geologie und Pal�ontologie

Abhandlungen 198 (3): 297–311. - Peter M. Galton -

1995.

- Cranial anatomy of the basal hypsilophodontid dinosaur

Thescelosaurus neglectus Gilmore (Ornithischia; Ornithopoda) from

the Upper Cretaceous of North America. - Revue Pal�obiologie,

Gen�ve 16 (1): 231–258. - Peter M. Galton - 1997.

- Cranial anatomy of the hypsilophodont dinosaur Bugenasaura

infernalis (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda) from the Upper Cretaceous

of North America. - Revue Pal�obiologie, Gen�ve 18 (2):

517–534. - Peter M. Galton - 1999.

- Technical comment: dinosaur with a heart of stone. - Science

291 (5505): 783a. - Timothy R. Rowe, Earle F. McBride

& Paul C. Sereno - 2001.

- Reply: dinosaur with a heart of stone. - Science 291

(5505): 783a. - Dale A. Russel, Paul E. Fisher, Reese

F. Barrick & Michael K. Stoskopf - 2001.

- Taxonomic revision of the basal neornithischian taxa Thescelosaurus

and Bugenasaura. - Journal of Vertebrate

Paleontology 29

(3): 758–770. - Clint A. Boyd, Caleb M. Brown,

Rodney D. Scheetz & Julia A. Clarke - 2009.

- Histological, chemical, and morphological reexamination of the

‘heart’ of a small Late Cretaceous Thescelosaurus.

-

Naturwissenschaften 98 (3): 203–211. - Timothy P.

Cleland, Michael K. Stoskopf & Mary H. Schweitzer -

2011.

- A new basal ornithopod dinosaur (Frenchman Formation,

Saskatchewan, Canada), and implications for late Maastrichtian

ornithischian diversity in North America. - Zoological Journal of

the Linnean Society 163 (4): 1157–1198. - Caleb M,

Brown, Clint A. Boyd & Anthony P. Russel - 2011.

Random favourites

|

|

|

|