Pelorosaurus

Name:

Pelorosaurus

(Monstrous lizard).

Phonetic: Pel-o-ro-sore-us.

Named By: Gideon Mantell - 1850.

Synonyms: Cetiosaurus conybeari.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria,

Saurischia, Sauropoda, Brachiosauridae.

Species: P. conybeari

(type).

Diet: Herbivore.

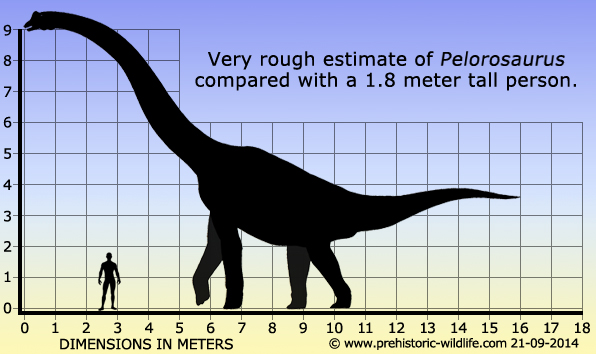

Size: Estimated about 16 meters long.

Known locations: England - Lower Greensand

Group, Wealden Group, and France.

Time period: Mid Tithonian to end of the early

Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: Various partial post cranial

remains.

The

first sauropod

dinosaur to ever be named was Cetiosaurus,

which was

named in 1841 by Richard Owen. Owen however did not realise that

he was dealing with a dinosaur, he actually thought that he was

dealing with a giant marine crocodile. The first sauropod to actually

be identified as a dinosaur was actually Pelorosaurus,

named in

1850 by Gideon Mantell, the man who named Iguanodon,

the first

plant eating dinosaur to be named, and second dinosaur overall (it

was narrowly beaten by Megalosaurus).

Understanding

the taxonomic history of Pelorosaurus from this

point can give you a

headache, but in simple facts its goes like this. After Cetiosaurus

was first named Owen named many species because of differences in

attributed remains, but it was later realised that some of these

fossils were from different animals, and not attributable to

Cetiosaurus. One species, Cetiosaurus

brevis was realised to have a

mix of sauropod and iguanodont bones by Alexander Melville, who

subsequently took the sauropod material to create a new species of

Cetiosaurus, C. conybeari,

in 1849. The ‘conybeari’ part

was in honour of William Conybeare, a geologist who published the

first ever description of a plesiosaur, creating the genus

Plesiosaurus

in 1821.

Then

in 1950 Gideon Mantell took the sauropod fossils of C.

conybeari

and realising them to be different from the others of the genus used

them to establish a new genus. Adding a humerus that was confirmed to

come from the original fossil site, Mantell knew that he was dealing

with a big animal, and at first considered Colossosaurus, initially

thinking that the Ancient Greek ‘kolossos’ meant giant, though

when he checked he realised that it actually meant ‘statue’ (to be

fair to Mantell, the most famous colossuses are generally very

large). Mantell instead went with Pelorosaurus

which means

‘monstrous lizard’ while the species name was kept as conybeari in

keeping with naming guidelines concerning the naming of animals.

This

would have been a simple case of naming a new genus from an established

species, something that is standard fare in naming animals. However

Richard Owen perceived the species and genus re-namings by Melville and

Mantell as attacks upon his credibility as a naturalist. Owen after

all held important positions in the fields of British natural history,

and would have course wanted to protect his authority to hold those

positions. Owen was also quick to try and alter the works of others,

including renaming already established genera (Basilosaurus

and

Ornithocheirus

to name but two). Some may note that Owen only

sought to be scientifically clear, but less kind critics might call

them deliberate attempts to stamp his name upon important discoveries.

Richard

Owen’s counter to the creation of Pelorosaurus

was to immediately

discredit the work of Melville and Mantell. He accused Mantell of not

understanding the meaning of the name ‘brevis’, as well as

claiming that his original 1842 description of the name was

intended as a basic description. Owen conceded that C. brevis was

likely a nomen nudum, but saw to fix this by assigning further

sauropod fossils. When dealing with the creation of the genus

Pelorosaurus, Owen removed all fossil material

with the exception of

the humerus that was added by Mantell. Then later in 1859, Owen

once again attributed iguanodontid vertebrae to Cetiosaurus

brevis.

Stating that any connection of Pelorosaurus to Cetiosaurus

was a

mistake, and satisfied that his Cetioasurus brevis

had been

preserved, this was last that anything was said about it for just

over a hundred years.

While

Owen was a leading figure in the early years of dinosaur

palaeontology, much of his work has not stood the test of time. A

1970 study by John Ostrom and Rodney Steel applied modern reasoning

to Owen’s attempts at preserving Cetiosaurus brevis.

Their

conclusions were that Owen had simply tried to replace the holotype of

Cetiosaurus brevis, something that should not have

been allowed,

and certainly could not be accepted today. Criticism was also made

of Melville’s decision to remove the sauropod fossils and not the

iguanodont fossils, which really should have been removed instead.

The

result is that even though Pelorosaurus is only

represented by a few

fossils, it has actually been seen as valid since the late Twentieth

century, with Cetiosaurus conybeari named as a

synonym to the genus.

A second species of Pelorsaurus, P.

becklesi which was named from

partial remains and skin impressions is no longer thought to represent

Pelorosaurus, but rather a different titanosaur

genus. Various

fossils from England and now also France have been assigned to

Pelorosaurus, though often as indeterminate beyond

a genus level.

Pelorosaurus

is usually considered to be ranged from the very end of the Jurassic to

possibly as the end of the early Cretaceous, though most remains seem

to be earlier in the early Cretaceous. The isolated nature of many

Pelorosaurus fossils has led to confusion about

this. Overall

Pelorosaurus is perceived to have been a

brachiosaurid sauropod,

approximately some sixteen meters in length. Pelorosaurus

may have

coexisted with other sauropods such as Xenoposeidon.

Further reading

- Report on British fossil reptiles, Part II. - Reports of the

British Association for the Advancement of Science, 11: 60-204.

- Richard Owen - 1842.

- Notes on the vertebral column of Iguanodon. - Philosophical

Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 139: 285-300. -

A. G. Melville - 1849.

- On the Pelorosaurus: an undescribed gigantic

terrestrial

reptile, whose remains are associated with those of the Iguanodon

and

other saurians in the strata of Tilgate Forest, in Sussex. -

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 140:

379-390. - G. A. Mantelli - 1850.

- Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Wealden and Purbeck

formations. - Palaeontological Society, London. - R. Owen

- 1853.

- Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Wealden and Purbeck

formations. Supplement no. II. Crocodilia (Streptospondylus,

etc.). [Wealden.] - The Palaeontographical Society, London

1857: 20-44. - R. Owen - 1859.

- Saurischia. Handbuch der Pal�oherpetologie/Encyclopedia of

Paleoherpetology. - Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart 1-87. -

R. Steel - 1970.

- An unusual new neosauropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous

Hastings Beds Group of East Sussex, England. - Palaeontology,

50(6): 1547-1564. - M. P. Taylor, D. Naish -

2007.

- Sauropod dinosaurs. In Batten, D. J. (ed.) English

Wealden Fossils. The Palaeontological Association (London),

pp. 476–525. - P. Upchurch, P. D. Mannion &

P. M. Barrett - 2011.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|