Charnia

Name: Charnia

(named after the Charnwood forest in England where the frist

specimens were found).

Phonetic: Char-ne-ah.

Named By: Trevor D. Ford - 1958.

Synonyms: Glassnerina, Rangea grandis,

Rangea sibirica.

Classification: Petalonamae.

Species: C, masoni (type),

C. grandis, C. siberica.

Diet: Possibly absorbed nutrients from water.

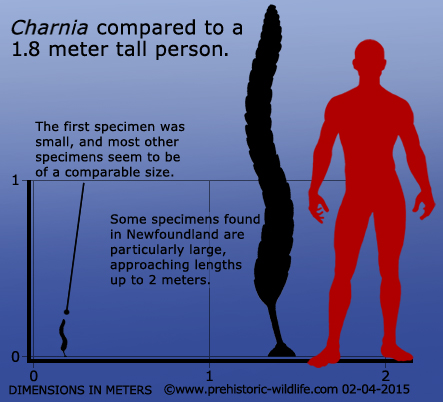

Size: Holotype specimen roughly about 19

centimetres long, with many other specimens of comparable size.

However largest recorded individuals from Newfoundland approach up to

2 meters in length.

Known locations: Australia. Canada. England.

Russia.

Time period: Ediacaran, roughly 575-544

million years ago.

Fossil representation: Numerous specimens, many of

which are complete.

The

first ever fossil of Charnia was found in England.

It seems that the

first time this fossil was recorded was in 1956 when a 15 year

old schoolgirl named Tina Ford reported seeing the fossil to her

geography teacher. However at the time it was established ‘fact’

that the rocks in the Charnwood forest were far too old to have

fossils in them, and were laid down before animals existed, and

hence the teacher dismissed Tina’s claims of the fossil. Then a year

later in 1957, a schoolboy named Roger Mason (who would go into a

career in geology) brought the specimen to the attention of

scientists, and in 1958 the fossil was identified and named as a

genus of Trevor Ford in 1958.

Charnia

without doubt is one of the oldest lifeforms that we know about

that once lived on our planet. Though resembling a frond of a fern,

as well as perceived to be an alga or even a sea pen when in the early

days of its study, the majority of modern day researchers are certain

that Charnia was more likely a different kind of

lifeform, though one

unlike anything we currently know about today, as well as a member of

a group that at this time does not seem to have had any surviving

descendants.

The

discovery of Charnia marked the first time that a

living organism

was found in rocks that that were older than the Cambrian period.

Before this discovery it was unthinkable by scientists at the time

that fossils could be found in rocks that were then loosely termed as

Precambrian. In addition to this there also so far does not seem to

have been any survival of Charnia beyond the

Ediacaran period. Unless

living examples are one day discovered in future deep sea

exploration, then it would seem that Charnia

represents an

evolutionary dead end.

There

is much still to learn about how Charnia lived.

Analysis of

fossil beds where Charnia has been found has led to

many people

concluding that Charnia lived in very deep water,

so deep in fact

that sunlight would have been unable to reach down that far. This

would make photosynthesis impossible at such depths, and is one of

the main arguments supporting the idea that Charnia

was not a plant.

Charnia does not seem to have been like known

animal groups either

however, which makes its position in current models of the tree of

life uncertain. It seems that the fern-like appearance of Charnia

is

a result of a very simple method of growth where a latticework of

tissues would grow in repeating patens, leading to the establishment

of the uniform appearance. As far as feeding goes, most researchers

agree that Charnia probably absorbed nutrients from

the water around

it, but the exact method of absorption is still currently a matter of

debate amongst researchers.

Further reading

- Pre-Cambrian fossils from Charnwood Forest. - Proceedings of

the Yorkshire Geological Society 31(3):211-217. - Trevor D.

Ford - 1958.

- First occurrence of the Ediacaran fossil Charnia

from the southern

hemisphere. - Alcheringa 22 (3/4): 315–316. - C.

Nedin & R. J. F. Jenkins - 1998.

- Morphology and taphonomy of an Ediacaran frond: Charnia

from the

Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland. - Geological Society, London,

Special Publications 286 (1): 237–257. - M. Laflamme,

G. M. Narbonne, C. Greentree & M. M. Anderson

- 2007.

- Charnia and sea pens are poles apart. -

Journal of Geological

Society 164 (1): 49. - J. B. Antcliffe, M. D.

Brasier - 2007.

- Charnia at 50: Developmental Models for

Ediacaran Fronds. -

Palaeontology 51 (1): 11–26. - J. B. Antcliffe,

M. D. Brasier - 2008.

Random favourites

|

|

|