Bandringa

Name: Bandringa.

Phonetic: Ban-dring-ah.

Named By: R. Zangerl - 1969.

Synonyms: Bandringa herdinae.

Classification: Chordata, Gnathostomata,

Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii, Ctenacanthiformes.

Species: B. rayi (type).

Diet: Carnivore.

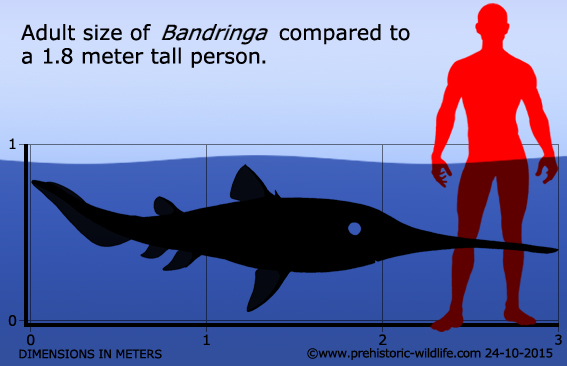

Size: Adults up to about 3 meters long.

Known locations: USA, Illinois - Carbondale

Formation. Pennsylvania. Ohio.

Time period: Moscovian of the Carboniferous.

Fossil representation: Numerous individuals, some

almost complete. Adults and juveniles both known.

Many

prehistoric sharks

look just plain weird, and Bandringa

is certainly

no exception. The immediate stand out feature of this shark is the

long spoonbill shaped snout that accounts for a good portion of the

sharks total length. Some fish we know today do have such a snout,

and they use it for digging out small aquatic animals that are

otherwise buried in soft sediment. With this comparison in mind it is

easy to envision Bandringa sharks hunting in a

similar manner.

Indeed, the mouth of Bandringa is orientated to

face more downwards

as opposed to forwards like in most other sharks.

Bandringa

was first named in 1969 by R. Zangerl with the type species as

B. rayi. Then ten years later Zangerl named a

second species,

B. herdinae. What stood out about these species

was that at up to

three meters in length the type species B. rayi

was much larger and

living in freshwater. B. herdinae however was

tiny in comparison,

only about ten to fifteen centimetres in length and living in

saltwater. Then in 2012 a new study by Lauren Cole Sallan and

Michael I Coates was penned and later published online in 2014, and

this would change a great deal about what we thought we knew about the

Bandringa genus.

The

main focus of the study by Sallan and Coates was the marine (salt

water) specimens of B. herdinae. For them the

problem with the

species was not the small size of the individuals, but the simple

observation that all known specimens of B. herdinae

were either

juveniles or egg cases, there were no known adults. Then in looking

at B. rayi, only adults had been attributed to

the type species.

Then by charting the known geographical locations for fossils, the

result was quite simple, Both B. rayi and B.

herdinae are in fact

one and the same species. Immediately this means that Bandringa

herdinae is now a synonym to Bandringa rayi,

but this also reveals a

very interesting and startling theory about this shark.

Adults

of Bandringa have so far always been found in

freshwater deposits. In

itself this is not unusual, many prehistoric sharks lived in

freshwater, and even today some cartilaginous fish, including the

bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) and some

stingrays are known to

enter and swim up freshwater river systems. But then why are the

juveniles only found in freshwater? The simple answer is that this is

one of the earliest confirmed cases of sharks actually migrating to a

nursery ground.

It

is not unknown for sharks to migrate to specific areas in order to lay

eggs or give birth to live young, it is after all behaviour that is

well documented. Even the fossil record supports this behaviour with

juvenile teeth of the giant shark C.

megalodon being much more

common than adult teeth in some shallow water environments such as

around central America and off the coast of Maryland, USA. What is

unusual here though is that the adults that are living in freshwater

are choosing to migrate from freshwater into saltwater.

Freshwater

to saltwater migration is known in some fish, best known of which is

the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) which

starts out life in the

Sargasso Sea before migrating into freshwater rivers and lakes where

they live for about five to twenty years before finally returning to

the Sargasso Sea to spawn. However up until the study by Sallan and

Coates such migration was completely unknown for sharks. Eels are

known to die in the Sargasso after spawning, but this may not have

been the case for Bandringa. Firstly sharks are

not known for dying

en masse after laying eggs, and the lack of adult fossils in with

the juveniles would indicate that adults would return to freshwater

ecosystems after egg laying.

One

question to be asked is why would Bandringa choose

to establish nursery

grounds in saltwater? Well so far all juveniles of Bandringa

were in

shallow coastal waters which would provide a number of benefits for

rearing young sharks. Shallow coastal waters usually have a

proportionately broad abundance of life with an almost unlimited number

of small aquatic animals, from worms, to shrimp and even some kinds

of fish buried in the soft sandy sediments. When an animal like a

shark is young large amounts of small animals is exactly what you need

to grow large fast. Coastal waters also restrict the movements of

larger predators enabling a greater chance of survival for small

juveniles. Coastal waters also tend to be much warmer, being more

easily heated by the sun and perhaps even being warmed by oceanic

currents, raising metabolic rates and increasing the rate of growth

than what would have been experienced in colder rivers systems.

The

same soft sediments that would have contained large amounts of prey

animals for juvenile Bandringa have also offered a

high level of

preservation in some of these juveniles with even soft tissues being

preserved. These have helped confirm the presence of some features

such as the downward facing mouth, as well as revealing new ones not

preserved in adults due to different fossilisation factors not

preserving them. These include small needle-like spines on the head

and cheeks, but also the presence of a vast array of electro

receptors that are on the snout. This confirms that like in other

sharks with long snouts, the snout of Bandringa

primarily served as a

sensory organ detecting buried prey, before then being used to dig

them out.

The

fact that we now know that one genus of shark migrated from freshwater

to saltwater to raise young in a nursery ground now raises the

question, how many other ‘freshwater’ sharks migrated to salt

water nursery grounds?

Further reading

- Bandringa rayi: A New Ctenacanthoid Shark

form the Pennsylvanian

Essex Fauna of Illinois. - Fieldiana Geology 12:157-169. -

R. Zangerl - 1969.

- New Chondrichthyes from the Mazon Creek fauna (Pennsylvanian)

of Illinois. - Mazon Creek Fossils 449-500. - R. Zangerl

- 1979.

- The long-rostrumed elasmobranch Bandringa Zangerl, 1969, and

taphonomy within a Carboniferous shark nursery. - Journal of

Vertebrate Paleontology vol 34, issue 1 - Lauren Cole Sallan

& Michael I Coates - 2014.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|