Helicoprion

This illustration is available as a printable colouring sheet. Just click here and right click on the image that opens in a new window and save to your computer.

Name:

Helicoprion

(Spiral saw).

Phonetic: Hel-e-co-pree-on.

Named By: Alexander Petrovich Karpinsky - 1899.

Synonyms: Lissoprion.

Classification: Chordata, Chondrichthyes,

Eugeneodontida, Agassizodontidae.

Species: H. bessonovi (type),

H.

davisii, H. ergasaminon, H. ferrieri, H. mexicanus, H.

nevadensis, H. svalis.

Diet: Carnivore/Picivore.

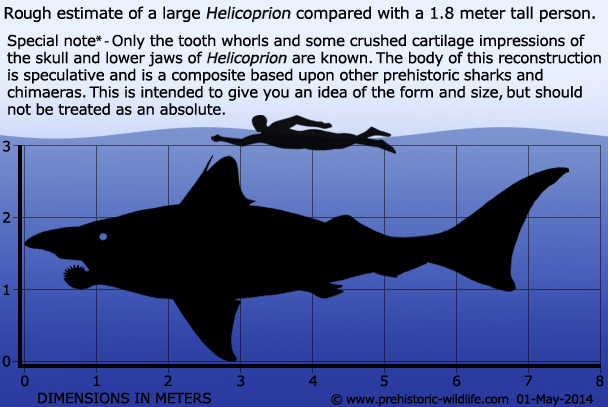

Size: Uncertain but more recent estimates place

larger Helicoprion at up to about 7.5 meters long.

Many specimens are

from smaller indviduals of about 3-4 meters long, suggesting a size

variation between species.

Known locations: Australia - Wandagee Formation,

Canada, Alberta - Ranger Canyon Formation, British Columbia - Fantasque

Formation, Nunavut - Assistance Formation, China - Qixia Formation,

Japan - Ochiai Formation andYagihawa limestone Formation, Kazakstan,

Mexico - Patlanoaya Formation, Russia, USA, California - Goodhue

Formation, Idaho - Phosphoria Formation, Montana - Phosphoria

Formation, Nevada - Antler Peak Formation, Texas - Bone Spring

Formation, Skinner Ranch Formation, Utah - Phosphoria Formation,

Wyoming - Phosphoria Formation. The broad distribution of fossil

locations suggests a global distribution.

Time period: Artinskian of the Permian through to

the Carnian of the Triassic.

Fossil representation: Mostly only known from the

'tooth-whorls', at least one specimen has been preserved with

crushed cartilage from the skull and jaw.

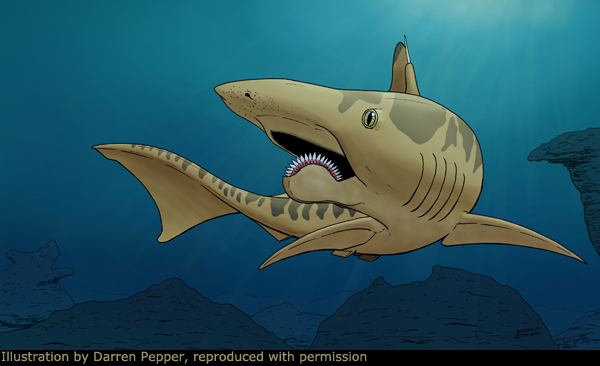

Helicoprion is one of the stranger 'sharks' in the fossil record, although at the time that Helicoprion swam the oceans there were actually many sharks that did not conform to the 'standard' form that we know today. The majority of the remains of this shark are the teeth which are fossilised in a spiral pattern like the shell of an ammonite, in fact when first discovered these fossils were actually thought to be some kind of exotic ammonite shell. These arrangements of fossil teeth are today referred to as a 'tooth-whorl'.

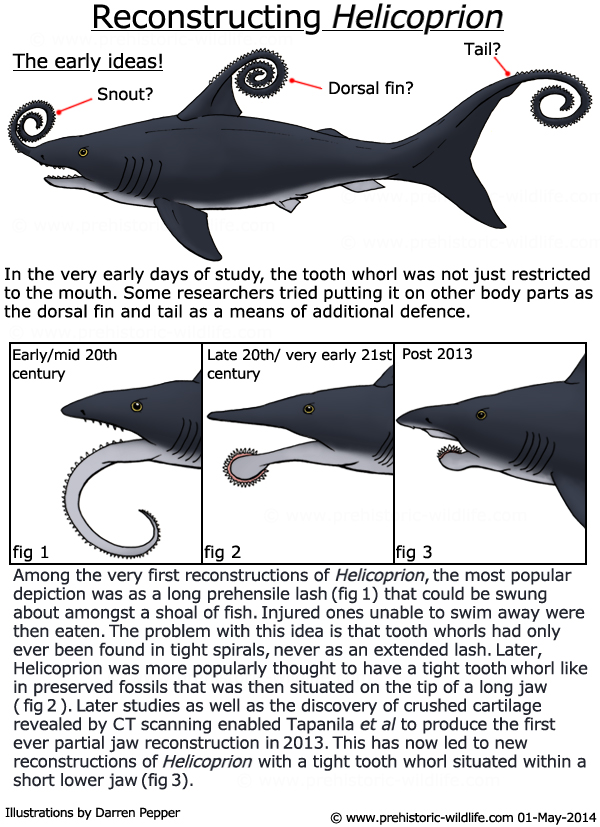

How

and where the tooth-whorl attached has been a source of puzzlement to

palaeoichthyologists ever since it was realised what it was, and

while the obvious choice might be to place the tooth-whorl within the

mouth, the whorl has on occasion been placed in different parts

including the dorsal fin and even the tail. Today the whorl is almost

always placed with the lower jaw, though for a long time not everyone

agreed with

the exact location. If the whorl was mounted on the tip it would

significantly increase the drag that Helicoprion

experienced as it swam

through the water. Not only would it require more effort to swim,

the greater water turbulence would have revealed the presence of

Helicoprion to its potential prey. This is why

many people now

consider the whorl to have been further back into the mouth.

Then

in 2013 a new study by Tapanila, Pruitt, Pradel, Wilga,

Ramsay, Schlader and Didier was published, and this was a

watershed moment in the study of Helicorpion as

this was the first time

that something other than the tooth whorl was studied; crushed

cartilage that once formed the head and jaw. Although incomplete,

the cartilage which was on a fossil found in Idaho in 1950 and

officially described in 1966, was completely revealed by a CT scan

which then enabled the researchers to use computer modelling to form a

reconstruction of Helicoprion. This study led to

a new depiction of

Helicoprion with a tooth whorl within a shorter

lower jaw.

How

Helicoprion used its whorl has also been another

matter of debate with

a variety of theories ranging from the whorl being used as a lash

against fish, to a rasp that cut its way through the shells of

ammonites with a sawing motion. However even a casual look at the

fossil tooth whorls reveals that the teeth have a surprising little

amount of wear, and since Helicoprion and

relative genera are not

thought to have had such a fast replacement of teeth modern day

sharks, there is now new speculation that Helicoprion

were predators

of soft bodied organisms such as molluscs, especially cephalopods

such as octopuses.

It

may now only be a matter of time before more cartilaginous remains of

Helicoprion are discovered, as other creatures with

cartilaginous

remains from genera such as Cladoselache,

Fadenia

and Stethacanthus

amongst a growing number of many others are being found.

Further reading

- Ueber die Reste von Edestiden und die neue Gattung Helicoprion.

-

Verhandlungen der Kaiserlichen Russischen Mineralogischen Gesellschaft

zu St. Petersburg, Zweite Series 36:1-111 - A. Karpinsky - 1899.

- A new genus and species of fossil shark related to Edestus

Leidy. -

Science 26(653):22-24 - O. P. Hay - 1907.

- Helicoprion ivanovi, n. sp. Bulletin de

l'Academie des Sciences de

Russie 16:369-378 - A. Karpinsky - 1922.

- Helicoprion in the Anthracolithic (Late

Paleozoic) of Nevada and

California, and its stratigraphic significance. - Journal of

Paleontology 13(1):103-114 - Harry E. Wheeler - 1939.

- Helicoprion from Elko County, Nevada. - Journal

of Paleontology 29

(5): 918–919. - E. R. Larson & J. B. Scott - 1955.

- New investigations on Helicoprion from the

Phosphoria Formation of

South-east Idaho, USA. - Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab,

Biologiske Skrifter 14(5):1-54 - S. E. Bendix-Almgreen - 1966.

- The first record of Helicoprion Karpinsky

(Helicoprionidae) from

China. - Chinese Science Bulletin 52 (16): 2246–2251. - Xiao-Hong Chen,

Long Cheng, Kai-Guo Yin - 2007.

- The Orthodonty of Helicoprion. - National Museum

of Natural History.

Smithsonian Institution. p. 1. - Robert W. Purdy - 2008.

- A new specimen of Helicoprion Karpinsky, 1899

from Kazakhstanian

Cisurals and a new reconstruction of its tooth whorl position and

function. - Acta Zoologica 90: 171–182. - O. A. Lebedev - 2009.

- Jaws for a spiral-tooth whorl: CT images reveal novel adaptation and

phylogeny in fossil Helicoprion. - Biology Letters

9 (2): 20130057 - L.

Tapanila, J. Pruitt, A. Pradel, C. D. Wilga, J. B. Ramsay, R. Schlader

& D. A. Didier - 2013.

- Unravelling species concepts for the Helicoprion

tooth whorl. -

Journal of Paleontology. 87 (6): 965–983. - L. Tapanila & J.

Pruitt - 2013.

- Eating with a saw for a jaw: Functional morphology of the jaws and

tooth-whorl in Helicoprion davisii: Jaw and Tooth

Function in

Helicoprion. - Journal of Morphology. 276 (1): 47–64. - Jason B.

Ramsay, Cheryl D. Wilga, Leif Tapanila, Jesse Pruitt, Alan Pradel,

Robert Schlader, & Dominique A. Didier - 2014.

- Saws, Scissors, and Sharks: Late Paleozoic Experimentation with

Symphyseal Dentition. - The Anatomical Record. 303 (2): 363–376. - Leif

Tapanila, Jesse Pruitt, Cheryl D. Wilga & Alan Pradel - 2020.

Random favourites

|

|

|

|