Alamosaurus

Name:

Alamosaurus

(Alamo lizard).

Phonetic: Al-ah-moe-sore-us.

Named By: Charles W. Gilmore - 1922.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria,

Saurischia, Sauropodomorpha, Sauropoda, Titanosauria,

Saltasauridae, Opisthocoelicaudiinae.

Species: A. sanjuanensis (type).

Diet: Herbivore.

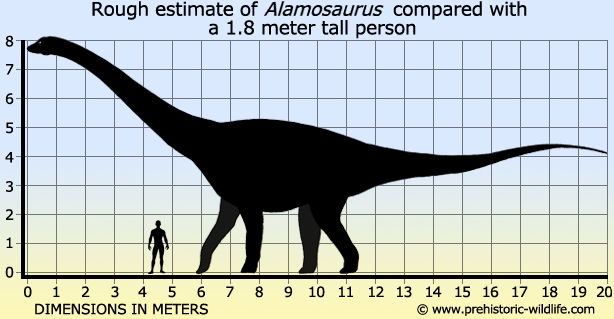

Size: Estimated around 20-24 meters long,

based

upon comparison between more complete juvenile remains and partial

adult remains. Some isolated remains suggest larger.

Known locations: USA, New Mexico - Ojo Alamo

Formation (possibly part of the Kirtland Formation, Utah -

North Horn Formation and Texas - Black Peaks Formation, El

Picacho Formation and Javelina Formation.

Time period: Maastrichtian of the Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: Specimens of many

individuals, although often of incomplete skeletons. Juvenile

specimens are also known. Skulls are still unknown.

The

one ‘fact’ that is often presented for Alamosaurus

is that it is

named after the Alamo, the famous mission in San Antonia that was the

site for one of the most important battles in the Texas Revolution.

However this is completely false and the truth of the matter is that

the first Alamosaurus remains which were found in

New Mexico were so

named because they came from the Ojo Alamo Formation.

Alamosaurus

was a reasonably large titanosaur,

the most common group of more

advanced sauropod dinosaurs that were the most common during the

Cretaceous. A complete adult specimen of Alamosaurus

continues to

prove elusive, although this is a common problem for most large

dinosaurs in general. Juveniles however are often more complete

because their smaller bodies are more easily covered by sediment, and

comparison of juvenile fossils with those of adults has led to

estimates of around twenty meters long, give or take a meter or two,

for adult Alamosaurus. A skull of Alamosaurus

is also currently

unknown, although associated teeth are quite slender, possibly for

snipping at tree tops. Alamosaurus also seems to

have lacked the

osteoderm armour (bony plates that grew in the skin) that is known

to be present in many other titanosaurs since out of all the known

Alamosaurus remains, no osteoderms have yet been

found.

More

importantly, the presence of Alamosaurus in the

south western

portions of the United States is proof that the sauropods had not

disappeared completely from North America during the Cretaceous.

Sauropods however are usually associated with dryer and higher up

landscapes, and these areas do not seem to have been that abundant,

due mainly to the Western interior Seaway submerging most of the

central portions of North America. As such it is quite conceivable

that the distribution of sauropods like with most animals is down to

the availability of suitable habitat.

How

Alamosaurus came to live within the United States at

the end of the

Cretaceous is a question that has caused some confusion for some since

for a long time the popular conception of sauropods was that they

mostly disappeared from North America at the end of the Jurassic.

This idea is based upon the observation that fossils of sauropods were

more common in North America at the end of the Jurassic, but seem to

have been replaced by ornithischians like hadrosaurs

and later on

ceratopsian

dinosaurs during the Cretaceous. However the saying that

absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence is commonly

used in palaeontology, and slowly but surely Cretaceous age sauropods

are slowly but surely being discovered in North America with examples

including Astrodon, Sauroposeidon

and Cedarosaurus

amongst others.

Slowly, Cretaceous sauropod (or rather more specifically

titanosaur) genera are coming together to help complete a picture of

the dinosaurian fauna of North American ecosystems where titanosaur

sauropods are actually still quite common, although still perhaps not

as common as their late Jurassic ancestors.

There

are too alternative theories concerning how Alamosaurus

came to live in

North America. One is a direct Asian origin where Alamosaurus

or

immediate ancestors to it crossed the Bering Strait land bridge and

spread down to the south-western regions where the habitat may have

remained more suitable for a stable and permanent population. This

is in part supported by the placement of Alamosaurus

within the

Opisthocoelicaudiinae group of titanosaurs, the type genus of which,

Opisthocoelicaudia,

is currently only known from Asia. However

this group also sits within the Saltasauridae and Alamosaurus

is seen

to have a lot of similarities with the type genus of this group,

Saltasaurus.

This has led to speculation of a South American origin

for Alamosaurus, although the main problem here

is that South America

is thought to have been separated from North America during the

Cretaceous by ocean. Additionally other strictly South American

dinosaurs such as the abelisaur theropods are still not known in North

America, and vice versa, North American dinosaurs like tyrannosaurs

are not known in South America.

Altogether

the arguments for a South American origin are not that convincing,

but one possibility that may explain these similarities is convergent

evolution. This is simply where two animals (or in this case

dinosaurs) that are separated by time and/or geography find

themselves in the same survival conditions and so physically change to

carry near identical adaptations for coping with their survival

requirements. This principal has been observed countless times, and

where the animals share a common ancestor and similar biology, the

similarity is just the more likely to occur.

Dinosaur

art and popular fiction often depicts life and death struggles between

large theropods such as tyrannosaurs and long necked sauropods. As

stated above this was long thought unlikely to have happened in North

America, but Alamosaurus did live in North

America at a time that

saw large tyrannosaurs

such as Daspletosaurus

and Bistahieversor

roaming the land in search of prey. A fully grown Alamosaurus

may

still have been too much of a challenge for these dinosaurs, but a

smaller juvenile would have certainly been within their predatory

scope. Other dinosaurs that Alamosaurus shared

its habitat with

include the ceratopsian dinosaur Torosaurus and the

hadrosaur

Edmontosaurus. Additionally it would have also

been possible to see

the giant pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus

soaring through the skies of the

time.

Further reading

- A new sauropod dinosaur from the Ojo Alamo Formation of New Mexico. -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 72(34):1-9 - Charles W. Gilmore -

1922.

- A juvenile specimen of the sauropod Alamosaurus sanjuanensis from the

Upper Cretaceous of Big Bend National Park, Texas. - Journal of

Palaeontology. 76(1): 156-172. - T. M. Lehman & A. B. Coulson -

2002.

- First isotopic (U-PB) age for the Late Creatceous Alamosaurus

vertebrate fauna of West Texas and its significance as a link between

two faunal provinces. - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26:

922-928. - T. M. Lehman, F. W. McDowell & J. N. Connelly -

2006.

- The First Giant Titanosaurian Sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of

North America. - Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (4): 685. - D. W.

Fowler & R. M. Sullivan - 2011.

- Osteoderms of the titanosaur sauropod dinosaur Alamosaurus

sanjuanensis Gilmore, 1922. - Journal of Vertebrate

Paleontology. 35

(1). - M. T. Carrano, M. D’Emic - 2015.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|