Balaur

Name: Balaur

(After a dragon in Romanian folklore).

Phonetic: Ba-la-ur.

Named By: Zoltan Csikil, Matyas Vremir, Stephen

L. Brusatte & mark A. Norell - 2010.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria,

Saurischia, Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae, Eudromaeosauria,

Velociraptorinae.

Species: B. bondoc (type).

Diet: Carnivore.

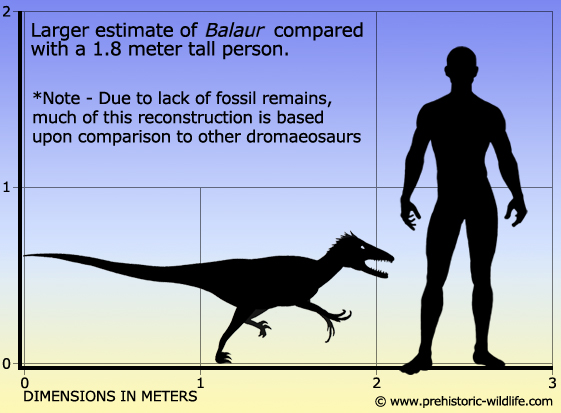

Size: Estimated between 1.8 and 2.1 meters

long.

Known locations: Romania - Sebes Formation.

Time period: Early Maastrichtian of the Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: Partial post cranial remains.

The

dromaeosaurids

are a very popular group of dinosaurs that all share a

few common features. These include reasonably lightweight build,

long stiff tails for balance, legs and pelvis adapted for very fast

running and a large sickle shaped claw on the second toe of each foot.

Balaur however is a dromaeosaur with a difference;

instead of having

one sickle shaped claw on each foot it had two. These claws were on

the second and first toes, and seem to be the principal killing

weapons since the hands are known to have one digit less than most

other known dromaeosaurids.

In

popular fiction the large

sickle claws are usually interpreted as slashing weapons that could

open up the side of an animal in a single stroke, an idea based upon

very early ideas about dinosaurs like Balaur.

However more modern

analysis has produced scenarios where the sickle claws are more suited

to stabbing rather than slashing. Additionally they may have also

been used for getting a grip onto similarly sized or larger prey, and

in the case of Balaur, the two sickle claws may

have been to

compensate for a lack of one of the hand digits.

Balaur

has a number of other

distinctive features that distinguish it from other dromaeosaurids,

but overall it seems to have been more heavily built than its

relatives. Palaeontologists are able to tell this because the bones,

particularly those of the limbs, are shorter and more robust than in

the closest relatives. This suggests that Balaur

was built for power

rather than high speed. It is curious that a dinosaur from a

typically fast and lightweight family line would deviate so much from

the others, but the reasons for why may be down to environmental

factors from where it lived.

So

far Balaur remains have

only been found in Romania from a part that back in the late Cretaceous

period was actually separated from the mainland. Today we now call

this landmass Hateg Island (after the Hateg Basin, which it would

form after its collision with mainland Europe), and this island is

particularly noted for the large variety of dinosaurs that have been

recovered from there. The most interesting fact about this dinosaur

is that they included varieties such as sauropods and ornithopod

hadrosauroids. On the mainland these varieties could comfortably grow

up to ten meters long and probably more for certain genera, but on

Hateg Island the typically large dinosaurs like sauropods grew much

smaller than their mainland relatives.

The

reason for this is a

process called insular dwarfism. Island ecosystems are fragile

because there is a reduced land mass for plants to grow upon. This

means that herbivorous animals that feed upon plants have less food,

and no option to search elsewhere because they are surrounded by so

many miles of sea, they cannot reach other areas upon the mainland.

Another factor to consider is that for a species of herbivores to

survive, you need many individuals, perhaps as many as a few

hundred to avoid any negative effects on inbreeding. The one logical

result for large animals that find themselves living in such restricted

ecosystems is that they grow smaller, something that means they do

not need to eat so much food, so they don’t exhaust the available

supply.

With

an estimated size around

the two meter mark, Balaur does not seem to have

grown small by

insular dwarfism, many mainland varieties of dromaeosaur also grew

to this size with some being larger, and some even being smaller.

But on Hateg Island Balaur would have had access

to dwarf sauropods

like Magyarosaurus

and hadrosaurids

like Telmatosaurus.

Although

much smaller than their mainland counterparts, these types of

herbivorous dinosaurs would have still been quite powerfully built,

and arguably not that fast, at least when compared to a

dromaeosaurid like Balaur. This could be where

the more muscular

legs and double sickle claws on each foot could have come in; they

would have given dinosaurs like Balaur a

significant edge when

attacking them. Additionally in the absence of large theropods like

those known in larger continental landmasses, dromaeosaurids like

Balaur would have found itself elevated to the

status of apex predator

for the ecosystems.

The

name Balaur is a

reference to a dragon in Romanian folklore. Although many prehistoric

animals have been after dragons (for example the archosaur Smok

was

named after a dragon in Polish folkore) the name has a double meaning

since dragons are seen as winged flying creatures, and dromaeosaurid

dinosaurs are treated as being very close to the ancestors of birds.

The type species name B. bondoc means ‘boned

oak’ and is based

upon the squat appearance of the holotype remains. Out of all the

other dromaeosaurids, Balaur is considered to be

most closely related

to those like Velociraptor

from Asia.

*Special note - While Hateg Island is especially well noted for its dwarf dinosaurs, at least one giant has been found there. This refers to the pterosaur Hatzegopteryx, and although known from only partial remains, these indicate that it was one of the largest pterosaurs of all time.

Further reading

- An aberrant island-dwelling theropod dinosaur from the Late

Cretaceous of Romania - Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

107(35):15357-15361 - Z. Csiki, M. Vremir, S. L. Brusatte & M.

A. Norell - 2010.

- The Osteology of Balaur bondoc, an

Island-Dwelling Dromaeosaurid

(Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Romania - Bulletin

of the American Museum of Natural History 374: 1-100. - S. L. Brusatte,

M. T. S. Vremir, Z. N. Csiki-Sava, A. H. Turner, A. Watanabe, G. M.

Erickson & M. A. Norell - 2013.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|