Hesperocyon

Name:

Hesperocyon

(Western dog).

Phonetic: Hess-per-oh-sie-on.

Named By: William Berryman Scott - 1890.

Synonyms: Alloeodectes mcgrewi,

Amphicyon gracilis, Canis gregarius, Cynodictis gregarius,

Cynodictis hylactor, Cynodictis paterculus, Galecynus gregarius,

Hesperocyon paterculus, Nanodelphys mcgrewi, Peradectes mcgrewi,

Pseudocynodictis gregarius, Pseudocynodictis paterculus.

Classification: Chordata, Mammalia, Carnivora,

Canida, Hesperocyoninae.

Species: H. gregarius

(type), H. coloradensis.

Diet: Carnivore.

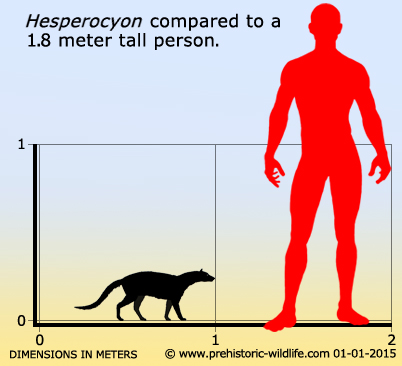

Size: Around 80 centimetres long.

Known locations: Canada - Saskatchewan. USA

- Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota

and Wyoming.

Time period: Late Lutetian of the Eocene through to

Rupelian of the Oligocene.

Fossil representation: Remains of well over 150

individuals.

In

overall form and proportions Hesperocyon wasn’t

much like a dog as we

know them today, but it has still been confirmed to be one of the

first canids to appear on the landscape. The key identifying feature

is the ear structure within the skull which is enclosed by bone rather

than cartiladge. Hesperocyon also has a total of

forty-two teeth,

two less than the forty-four standard that are seen more primitive

mammalian forms. Tooth reduction is an on-going character trait

within the Carnivora with continuing advancements and specialisations

resulting in much lower tooth counts like those seen in carnivoran

mammals today. Hesperocyon also has the

characteristic carnassial

teeth (specialised meat shearing teeth) that are common features in

the mouths of the members of the Carnivora. Like with most modern

dogs, Hesperocyon was probably primarily a

carnivore, but may have

also included occasionally plants, especially seasonal fruits and

vegetables that had fallen to the ground into its diet.

Like

with most predators of the Eocene era, Hesperocyon

had legs that were

proportionately shorter than those of later mammalian predators. This

is a reflection of Eocene era ecosystems that had a denser coverage of

forest than later periods, and were conducive for the implementation

of ambush rather than pursuit hunting tactics due to the reduced open

spaces. Here shorter legs would impart a limit upon top running

speed, but a much faster degree of acceleration. Also consider that

most of the available prey animals of the time also had proportionately

short legs, and it’s easy to appreciate that Hesperocyon

had all

that it needed to be an effective hunter during the Eocene of North

America.

However

the ecosystems of this time were slowly changing to a cooler, drier

and most importantly more open landscape. This was a very slow

process that started in the Eocene that would continue all the way

towards the Pleistocene, but it also forced a shift into newer longer

legged (and hence ultimately faster) animals appearing across the

world. With prey that was capable of outrunning Hesperocyon,

and

newer better adapted predators outcompeting it, Hesperocyon

were

already living upon borrowed time by the start of the Oligocene.

Further reading

- Multiple hereditary osteochondroma in Oligocene

Hesperocyon

(Carnivora: Canidae). - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology volume 12,

issue 3 - Xiaoming Wang & Bruce M. Rothschild - 1991.

- Phylogenetic systematics of the Hesperocyoninae (Carnivora, Canidae).

- Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 221:1-207. - X.

Wang - 1994.

Random favourites

|

|

|

|