Daeodon

(now includes Dinohyus)

Name: Daeodon

(Hostile tooth - alternatively, Destructive tooth).

Phonetic: Day-oh-don.

Named By: Edward Drinker Cope - 1879.

Synonyms: Ammodon, Boochoerus,

Dinochoerus, Dinohyus.

Classification: Chordata, Mammalia,

Artiodactyla, Entelodontidae.

Species: D. shoshonensis (type).

Diet: Carnivore/Omnivore?

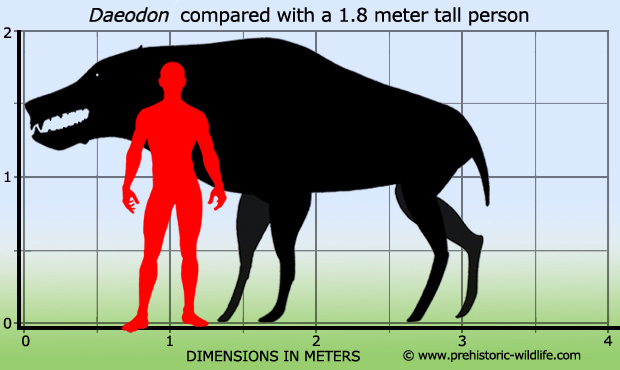

Size: 3.6 meters long, 1.8 meters tall at the

shoulder.

Known locations: North America.

Time period: Aquitanian to Burdigalian of the

Miocene.

Fossil representation: Several specimens.

There

was once another well-known enteledont

called Dinohyus

(terrible

pig) that was once the most well-known of the entelodonts. However

later study towards the end of the twentieth century brought the

realisation that Dinohyus was actually the same as

another genus of

entelodont called Daeodon. Under international

rules governing the

naming of animals, the oldest name has priority by default. This

means that Dinohyus which was named by Peterson in

1905 is now a

synonym to Daeodon which was named twenty-six years

earlier in 1879.

Despite this decision being accepted by palaeontologists for many

years now, there are still some inaccurate sources that continued to

treat Dinohyus as a valid genus even after it was

synonymised with

Daeodon.

Daeodon

was easily one of the largest known entelodonts, although other

genera such as Paraentelodon

as well as the type genus of the

Entelodontidae, Entelodon,

seem to have been comparable in size.

The ninety centimetre long skull of Daeodon is

mostly jaw with two

wide jugals (cheek bones). The wide jugals are thought to have

allowed for the attachment of powerful biting muscles although they

also seem to have been larger in males. This sign of sexual

dimorphism may have been to allow males to have more powerful bites for

fighting with other males, or even making it harder for a rival to

clamp its jaws around its skull, or indeed both.

Because

Daeodon has a mix of different tooth types it has

been imagined to be

an omnivore capable of foraging for plants, particularly certain

parts like roots and tubers, as well as perhaps scavenging carrion,

just like warthogs have been seen to do in Africa today. Although

pig like however, it is still not certain how close entelodonts are

related to pigs, or even if at all. But a carrion scavenger theory

might fit Daeodon better than that of an omnivore.

While easily

capable of killing and equally sized or smaller animal, popular

theories have suggested that entelodonts would track other predators

just to steal their kills, evidence of which come from a zigzagged

entelodont track way that may have been left by an earlier relative of

Daeodon called Archaeotherium.

Further

support for a scavenger theory comes from the arrangement of the

nostrils which in Daeodon seem to have faced out to

the sides rather

than directly forwards. This would allow for the development of a

directional sense of smell since depending upon which direction the

head was facing in relation to the wind, one nostril would pick up a

scent a fraction of a second before the other (similar to how when

you hear a sound you might hear it in one ear before the other,

telling you which way to turn to see what it was). Daeodon

might

have been able to keep on tracking in a zigzag pattern until the point

that the strength of the smell was equal in both nostrils so that it

would then know to just go straight ahead.

Once

a carcass was found it might already have another rival predator

feeding at it, but Daeodon would be to use its

immense bulk to

intimidate and drive another, especially smaller, predator away.

In this scenario it’s likely that by the time that Daeodon

actually

got there most of the choice pieces of flesh would have already been

consumed, but this is where Daeodon would make

real use of the strong

bite force of the jaws. This bite force would have allowed a large

entelodont like Daeodon to break and crack open

bones, especially

when caught between the posterior teeth that were closer to the fulcrum

of the jaw articulation since here the full strength of the jaw closing

muscles could have been brought to bear against whatever was in the

mouth. One final observation that supports a diet of other animals is

not actually on Daeodon itself, but the fossils

of other mammals,

especially herbivores, that have marks on them which closely match

the dental pattern and arrangement of entelodont jaws.

Further reading

- On some of the characters of the Miocene fauna of Oregon. -

Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 18(102):63-78. - E.

D. Cope - 1878.

- Taxonomy and distribution of Daeodon, an

Oligocene-Miocene entelodont

(Mammalia: Artiodactyla) from North America. - Proceedings of the

Biological Society of Washington. 111 (2): 425–435. - S. G. Lucas, R.

J. Emry & S. E. Foss - 1998.

Random favourites

|

|

|