Barosaurus

Name:

Barosaurus

(heavy lizard).

Phonetic: Bar-roe-sore-us.

Named By: Othniel Charles Marsh - 1890.

Synonyms: Barosaurus affinis.

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria,

Saurischia, Sauropodomorpha, Sauropoda, Diplodocidae,

Diplodocinae.

Species: B. lentus (type).

Diet: Herbivore.

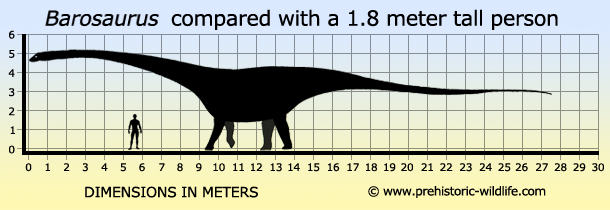

Size: Up to about 27.5 meters long (based upon

ROM 3670).

Known locations: USA, including the states of

Colorado, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Utah and Wyoming -

Morrison Formation.

Time period: Late Kimmeridgian of the Jurassic.

Fossil representation: Partial post cranial remains

of several individuals.

The

modern history of the sauropod

dinosaur Barosaurus

begins in 1889

with the discovery of the first Barosaurus fossils

by a Ms E. R.

Ellerman in South Dakota. Six caudal (tail) vertebrae were

subsequently recovered by the famous American palaeontologist Othniel

Charles Marsh later that year, though other remains were left at the

site until such time that they could be safely recovered and

transported. In 1898 one of Marsh’s assistants, George Weiland

recovered these remains which included limbs, ribs and more

vertebrae, and allowed for the identification of Barosaurus

as a

diplodocid sauropod. Later, fossils of Barosaurus

were the last to

ever be described by Charles Othniel Marsh before his death in 1899.

These were two metatarsals assigned to a new species, B.

affinis,

though today this species is treated as a synonym to the type

species, B. lentus.

Today

Barosaurus is known by the remains of several

individuals that have all

been recovered from the Kimmeridgian aged deposits of the famous

Morrison Formation. As already mentioned, Barosaurus

is a

diplodocid sauropod, which means that it was of the kind that were

very long with slender necks and tails that were whip-like on the end.

It should be mentioned at this point that the end of the tail of

Barosaurus is still unknown at the time of writing,

but it would be

highly unusual for a diplodocid to not have a whip-like tail.

Barosaurus can be further classified as a

diplodocine diplodocid

rather than an apatosaurine diplodosaurid. Diplodocines are classed

under the Diplodocinae and they are different to the apatosaurines

(classed under the Apatosaurinae) in that they are more gracile

(lightly built) than their heavier cousins.

The

main features that make Barosaurus unique to other

diplodocids are in

the vertebrae, and usually Barosaurus is compared

to the famous

Diplodocus

and Apatosaurus

. Both Diplodocus

and Apatosaurus

have fifteen cervical (neck) and ten dorsal (back) vertebrae.

Barosaurus is known to have had fifteen cervical

vertebrae but only

nine dorsal vertebrae. Where the tenth dorsal vertebra went to is

unknown, but it’s possible that it may have over time adapted to

become a sixteenth cervical vertebrae. The cervical vertebrae of

Barosaurus were also up to one and a half times

longer than the

cervical vertebrae of Diplodocus meaning that Barosaurus

would have

proportionately longer neck than Diplodocus. The

caudal (tail)

vertebrae of Barosaurus however were

proportionately shorter than

those of Diplodocus, meaning that the overall

length of the tail

would have been shorter in Barosaurus. The neural

spines of the

vertebrae in Barosaurus are also shorter and less

complex than those of

Diplodocus.

Much

of the post cranial skeleton of Barosaurus is

known, though there are

two glaring omissions; the feet and the head. Barosaurus

is

actually not an exception, the feet and skulls are the two most

commonly missing parts when sauropod remains are found. This is

because they are fairly small and jointed and therefore can become

easily detached from the rest of the skeleton before preservation. As

a diplodocid, Barosaurus would be expected to

have had a skull

similar to relative genera, elongated with a sloping snout, housing

peg-like teeth for stripping vegetation from branches.

Aside

from being similar to Diplodocus and Apatosaurus,

Barosaurus also

seems to have shared the same habitats as them as well. Another

sauropod named Haplocanthosaurus

may have also come into contact with

Barosaurus. In addition to these, macronarian

sauropods such as

Camarasaurus

and Brachiosaurus

would have also been present on the same

landscapes as Barosaurus. There would have course

been other

dinosaurs such as herbivores like Stegosaurus,

Camptosaurus

and

Mymoorapelta,

and predators such as Ornitholestes,

Torvosaurus,

Saurophaganax

and Allosaurus.

Barosaurus may have fallen prey to

some of these larger predators, though the smaller juveniles would

have been at more of a risk than fully grown adults.

For

a time Barosaurus was once thought to have lived in

Africa as well as

North America. This all comes down to a 1907 discovery of two

sauropod skeletons by a German palaeontologist named Eberhard Fraas,

who at the time thought that he was creating a new genus of sauropod

named Gigantosaurus.

However, the name Gigantosaurus had already

been named for a more obscure set of sauropod remains from England,

so a new genus was erected for them by Richard Sternfeld and named

Tornieria in 1911. Fossils of Tornieria africana

however were

re-assigned by another German palaeontologist named Werner Janensch to

Barosaurus. Since this however, other

palaeontologists have

questioned the reasoning of such a move. One species formerly known

as T. robustus was re-examined in 1991 and

revealed to be a

titanosaurs and added to its own new genus Janenschia.

Other material

once assigned as T. africanus was confirmed to be

different to known

North American diplodocids in 2006, which saw a subsequent

resurrection of the Tornieria genus. This also

rather obviously means

that Barosaurus remains known only from North

American deposits.

ROM

3670

One

of the most exciting discoveries, or rather rediscoveries concerning

Barosaurus happened in 2007. Palaeontologist and

curator of the

Royal Ontario Museum David Evans spotted a reference to a Barosaurus

skeleton that had been traded with the Carnegie Museum and sent to the

Royal Ontario Museum in 1962. Strangely, these fossils don’t seem

to have made it out of storage upon arriving and just disappeared from

everyone’s memory. Realising that there might be a scientifically

valuable specimen somewhere in the museum, Evans searched the storage

bays and began finding the fossils of the missing Barosaurus.

This

Barosaurus specimen is known as ROM 3670, though

those who visit

and work with it know it better as ‘Gordo’. With the rediscovery

plans were immediately put into motion to set up a new display,

though in order to get the display ready, not all of the fossil

casts could be mounted in time. In fact more bones of Barosaurus

were

still in storage several years after this mounting was completed which

means that it may be re-mounted but more completely in the future.

Unfortunately the skull is still not known, so the one that appears

upon the display is that of a Diplodocus, which

should at the very

least be a fairly close match.

ROM

3670 is valuable for two reasons. With more fossils of this

dinosaur coming out of storage, it may actually be the most complete

Barosaurus skeleton so far recovered. This

skeleton also seems to

have come from an individual which seems to have grown up to

twenty-seven and a half meters long, making it the largest individual

Barosaurus known.

Further reading

- Description of new dinosaurian reptiles - Othniel Charles

Marsh - 1890.

- The sauropod dinosaur Barosaurus Marsh:

redescription of the type

specimens in the Peabody Museum, Yale University - Richard S,

Lull - 1919.

- Sauropod dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic),

Black Hills, South Dakota and Wyoming - John R. Foster -

1996.

- A phylogenetic analysis of Diplodocoidea (Saurischia:

Sauropoda) J. A. Whitlock - 2011.

- The neck of Barosaurus was not only longer but

also wider than those

of Diplodocus and other diplodocines. - PeerJ Preprints. 1: e67v1. -

Michael P. taylor & Mathew J. Wedel - 2013.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|

|