Arctodus

(Short faced bear)

Name: Arctodus

(Bear tooth).

Phonetic: Ark-toe-dus.

Named By: Joseph Leidy - 1854.

Synonyms: Tremarctotherium.

Classification: Chordata, Mammalia, Carnivora,

Ursidae, Tremarctinae, Tremarctini.

Species: A. pristinus

(type), A.

simus.

Diet: Omnivore.

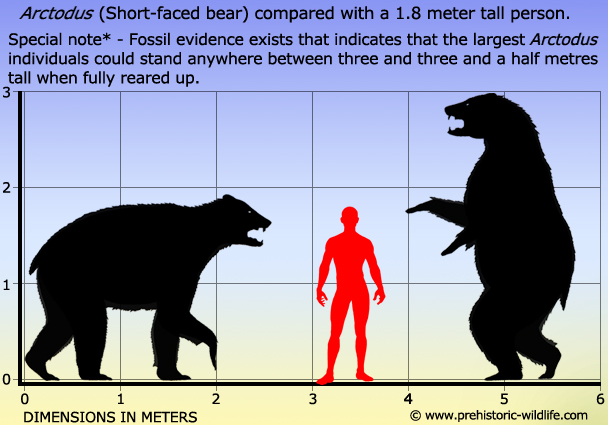

Size: About 1.6 to 1.8 meters tall at the

shoulder, when on

all fours. Weight estimated at up to 800 kg.

Known locations: Throughout North America.

Time period: Pleistocene.

Fossil representation: Multiple specimens.

Arctodus is not a very well-known name, but this ursine has appeared repeatedly in the popular media under the more common name of ‘Short faced bear’. Arctodus is closely related to another similar bear called Arctotherium which is known from South America. While larger specimens (thought to be mature males) of Arctodus may have been slightly larger in terms of skeletal size, Arctotherium had a more robust build that made it the heavier, and thus larger bear.

Arctodus -

predator or

scavenger?

With

such an immense size and obviously powerful jaws it’s tempting to paint

a picture of Arctodus as an apex predator that

could kill anything it

wanted. However, real science is not based upon assumptions that

are established upon superficial glances but on in depth study of the

available fossil material. With this in mind the analysis of Arctodus

remains has led to a surprising but very plausible theory about its

nature and behaviour.

Many

Pleistocene mammal fossils have been subjected to a process termed

oxygen isotope analysis. This is based upon the principal that

different environments have different isotope levels which get absorbed

by the plants growing on them. As these plants are eaten the isotopes

are absorbed and stored in the herbivores tissues as a marker that

allows palaeontologists to establish which types of animal were active

in which environment and what they were eating. In turn as these

herbivores were killed and eaten by carnivores the isotopes get

re-absorbed into the carnivores’ bodies which reveal roughly which

animals were being eaten by which carnivores (for example the sabre

toothed cat Smilodon

seems to have had a preference for bison).

The

analysis for Arctodus shows that it was what is

termed a

hypercarnivore, an animal that has a diet where seventy to a hundred

per cent of the eaten food is the tissue from other animals. However

it also revealed that Arctodus ate all kinds of

animals, and did not

specialise in just one type of prey, something that is highly unusual

for a predator, but quite normal for a scavenger.

The

skeleton also reveals hints to both the travelling and predatory

ability of Arctodus, with special reference to

the long limbs.

These could be seen as giving Arctodus a

significant reach advantage

that allowed it to swipe at prey animals, but the problem here is

that first Arctodus would have to get close enough

to its prey to do

this. In terms of speed the long legs with their broad strides are

thought to have given Arctodus a top speed

approaching fifty kilometres

an hour, something that would have seen it able to comfortably match

most of the available prey species.

However

these same legs are proportionally much thinner than they are in other

running animals, and are considered too fragile to be able to support

a heavy animal like Arctodus if it made a sharp

turn when running at

speed. This could mean an injury such as a break or dislocation that

probably would have been serious enough to cause the death of the

injured bear as it could no longer move about. But it is actually

these long legs that further support the scavenger theory as since they

are lightweight they would not require a great amount of effort to

move. Additionally the long sweeping arc of the feet meant that

Arctodus could comfortably cover more ground with

each step, making

locomotion such as walking or even running extremely energy efficient.

This means that Arctodus could cover territories

that spanned several

hundred square kilometres on a reduced amount of food than would be

required by a dedicated predator. This is a vital survival adaptation

when you consider that a scavenger does not know when or where its next

meal is coming from.

Another

clue comes from the immense size of the body. Arctodus simus

was the

largest carnivorous mammal currently known from Pleistocene North

America, and possibly the largest carnivorous animal since dinosaurs

like Tyrannosaurus disappeared at the end of the

Cretaceous period.

As such it’s extremely unlikely that the other Pleistocene predators

would have put up much of a fight and risked injury or even death from

a more powerful animal. This behaviour has been well documented in

modern times where grizzly bears will walk in and steal kills away from

packs of grey wolves that let the more powerful predator take what it

wants rather than risking injury.

The

final support for Arctodus being a scavenger comes

from the skull.

Arctodus is known as the short faced bear because

its snout is

proportionately shorter than that of other bear genera. These means

that when food is placed in the mouth it is nearer the fulcrum (point

of articulation) of the skull and mandible (lower jaw). This

focuses a greater amount of pressure from the jaw muscles onto whatever

is between the jaws, and seems to have been an adaptation that

allowed Arctodus to crack open bones to get at the

marrow within them.

This is another key survival adaptation as Arctodus

would inevitably

come across carcasses that had already been picked clean, but the

bones still in place because the predators that killed the animal were

unable to crunch the bones open. Even more critical to survival is

the fact that bone marrow can remain nutritious for months and even

years after an animal dies, something that would help Arctodus

to

survive even when there were no fresh kills to steal. Also fossil

evidence of large bison bones exist that look like they have been

bitten open by an animal like Arctodus, a feat

that would be beyond

the scope of smaller predators like wolves.

Arctodus

also had a proportionately large nasal opening in the front of its

skull which indicates that it was capable of sampling a larger volume

of air for scents. This coupled with the bears larger size meant that

it could sniff out and sample scents that were being carried higher

up, possibly to the point of detecting a carcass from several

kilometres away by smell alone. All of these factors combined point

to the short faced bear Arctodus being a much

specialised scavenging

animal.

Evidence

and studies now also suggest that Arctodus was

likely

omnivorous like modern bear species.

Why the short faced bear Arctodus

and the other megafauna became extinct.

Bearing

in mind the almost certain possibility that Arctodus

was a specialised

scavenger it would have been reliant upon two things. The first is

the presence of other large mammals that could provide enough

sustenance to live on, and the second is other predators powerful

enough to kill them. The end of the Pleistocene age in North America

is marked by a disappearance of the megafauna that had for a long time

populated this continent. Not only does this mean that everything

from mammoths to camels went extinct, but most of the larger and

more powerful predators such as Smilodon, the American

Lion and Dire

wolves also declined and eventually disappeared

because there was no

more large prey for them to hunt. With the loss of both factors

critical to the survival of Arctodus gone, it was

only a matter of

time before it followed them into extinction.

How

this extinction happened is a controversial subject as there is no one

explanation that comfortably covers the whole extinction. One is that

the last glaciation of the Pleistocene finished the megafauna. The

problem here is that this was but one of eleven major glaciation

periods that occurred throughout the Pleistocene, with the previous

ten not eradicating the megafauna. With this in mind either the last

glaciation was exceptionally severe, something that is partially

supported by analysis of ice cores, or it was not the only reason.

Perhaps

the most popular theory that supports this extinction is the appearance

of human settlers who had crossed over the Bering land bridge from

Asia. These people are known as ‘Clovis people’ because of their

use of Clovis points that tipped wooden spears that these people

launched from special spear throwers called an atlatl. These weapons

combined with human intelligence would have made the Clovis people the

most formidable hunters to so far set foot upon North America.

How

the Clovis people interacted with their environment is a further matter

of controversy as some researchers believe that they went upon a

killing spree across North America that wiped out the traditional prey

species like mammoth and camel, with several fossil sites showing

human butchering of carcasses. Another theory is that the carnivores

like Smilodon were deliberately eradicated to remove them as

competition to the available prey, although to date there is no

evidence to suggest that the Clovis people did this. Today neither of

these theories is widely accepted as while Clovis people did hunt the

animals of North America, there is insufficient evidence to suggest

that they alone hunted the megafauna into extinction. Also early

humans managed to live in other areas of the world alongside other

megafauna for much longer.

The

reality is probably a combination of the above two events. Animals

had survived previous glaciations before, but times would still have

been hard with the sick, old and weak being more susceptible to

succumbing to the harsh climatic conditions of the time. This likely

meant that the Clovis people that were also trying to survive only had

access to reduced populations of animals, which meant that their

actions would have had a greater long term impact as fewer animals were

surviving to reproduce. Additionally factor in the presence of other

carnivorous animals and you get a picture of an ecosystem that is

stressed beyond its ability to support such a large and diverse range

of creatures.

With

the large prey species reduced to numbers that they could not recover

from and dying out, the larger predators were unable to hunt the

smaller and more agile prey animals and also began to decline and

disappear as well. With no more large scale kills to steal,

Arctodus too disappeared from the landscape. The

Clovis people by

contrast could hunt any size of animal with their spears, and had the

intelligence to adapt accordingly to different challenges. Also the

smaller cousin of the short faced bear, the grizzly (Ursus

arctos

horribilis) is an opportunistic omnivore that explores its

environment to eat everything from fruits, to insects to even

occasionally killing its own prey. This adaptability is why the

grizzly survived this time, and the over specialised Arctodus

disappeared.

Further reading

- A new record of giant short-faced bear, Arctodus simus,

from western

North America with a re-evaluation of its paleobiology. - Contributions

in Science, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County 371:1-12. - S.

D. Emslie & N. J. Czaplewski - 1985.

- The short-faced bear Arctodus simus from the late

Quaternary in the

Wasatch Mountains of central Utah. - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology

12(1):107-112. - D. D. Gillette & D. B. Madsen - 1992.

- Arctodus simus from the Alaskan Arctic Slope. - Canadian Journal of

Earth Sciences 30(5):1007-1013, collected by A. V. Morgan - C. S.

Churcher, A. V. Morgan & L. D. Carter - 1993.

- Distribution and size variation in North American short-faced bears,

Arctodus simus. - Paleoecology and paleoenvironments

of Late Cenozoic

mammals 191-246. - R. Richards, C. S. Churcher & W. D. Turnbull

- 1996.

- What size were Arctodus simus and Ursus

spelaeus (Carnivora:

Ursidae)? - Annales Zoologici Fennici 36: 93–102. - Per Christiansen -

1999.

- A partial short-faced bear skeleton from an Ozark cave with comments

on the paleobiology of the species. - Journal of Cave and Karst Studies

65(2):101-110. - B. W. Schubert and J. E. Kaufmann - 2003.

- Ecomorphological correlates of craniodental variation in bears and

paleobiological implications for extinct taxa: an approach based on

geometric morphometrics - Journal of Zoology Volume 277, Issue 1, pages

70–80 - B. Figueirido, P. Palmqvist & J. A. P�rez-Claros - 2010.

- Demythologizing Arctodus simus, the ‘short-faced.

- Journal of

Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (1): 262–275. - Borja Figueirido, Juan A.

P�rez-Claros, Vanessa Torregrosa, Alberto Mart�n-Serra & Paul

Palmqvist - 2010.

- Giant short-faced bear (Arctodus simus) from late

Wisconsinan

deposits at Cowichan Head, Vancouver Island, British Columbia -

Canadian Journal Earth Sciences, v. 47:1029-1036 - Martina L. Steffen

& C. R. Steffen - 2010.

- Cursorial Adaptations in the Forelimb of the Giant Short-Faced Bear,

Arctodus simus, Revealed by Traditional and 3D

Landmark Morphometrics -

EAST TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY, 247 pages - Eric R. Lynch M. S. - 2012.

- Was the Giant Short-Faced Bear a Hyper-Scavenger? A New Approach to

the Dietary Study of Ursids Using Dental Microwear Textures - PLoS ONE

8(10): e77531. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077531. - Shelly L. Donohue,

Larisa R. G. DeSantis, Blaine W. Schubert, Peter S. Ungar - 2013.

- Dental caries in the fossil record: A window to the evolution of

dietary plasticity in an extinct bear. - Scientific Reports. 7 (1):

17813. - Borja Figueirido, Alejandro Perez, Blaine W Schubert,

Francisco Jos� Serrano, Aisling Farrell, Francisco Pastor, Aline A

Neves & Alejandro Romero - 2017.

- Ancient genomes reveal hybridisation between extinct short-faced

bears and the extant spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus).- Alexander T

Salis, Graham Gower, Blaine W. Schubert, Leopoldo H. Soibelzon, Holly

Heiniger, Alfredo Prieto, Francisco J. Prevosti, Julie Meachen, Alan

Cooper & Kieren J. Mitchell - 2021.

- Dietary niche separation of three Late Pleistocene bear species from

Vancouver Island, on the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. -

Journal of Quaternary Science: jqs.3451. - Cara Kubiak, Vaughan Grimes,

Geert Van Biesen, Grant Keddie, Mike Buckley, Reba Macdonald &

M. P. Richards - 2022.

Random favourites

|

|

|

|